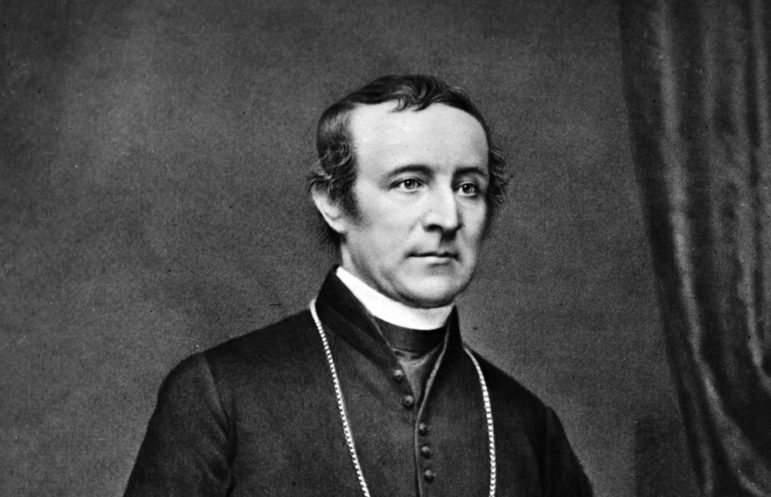

Libary of Congress

John Hughes who served as archbishop of New York between 1842 and 1864, became known as ‘Dagger John’ because he drew a cross before his signature. The prefix also seemed to describe his personality.

Dagger John, Archbishop:

John Hughes and the Making of Irish America

By John Loughery

Cornell University press 407p

Yesterday I took a three-minute walk across Fordham University’s Bronx campus to the front of the administration building, the 19th century manor house, to check out the statue of John “Dagger John” Hughes, who founded what was intended to be a mixed seminary for the New York diocese and a grammar and high school—they called them “colleges” then—for the male children of immigrants. In a sense, the school was for people like himself, immigrant Irish boys fleeing a nation that was falling apart to a new world that offered hope. According to old photographs, a good many young men were sent by their families from Latin America, perhaps to learn language and business skills to help them get ahead back home.

Why does Dagger John matter? He was a natural leader. He moved into major cities and found them in chaos, but he had a vision, an understanding of the church as a community that could be rescued by the ideals and discipline he had acquired through both physical work and religious training. As a leader he devoted himself especially to the weak and the poor, which included the large Irish immigrant population of the major cities. He raised money both from his congregations and donors throughout Europe. As an orator he spread confidence and hope. He built 10 new churches including St. Stephens, the most beautiful church in New York, and planned and began the building of New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral. For the sick he built St. Vincent’s Hospital, and for the education of Catholics, founded St. John’s College, which grew into Fordham University. He systematically organized Catholic voters and strongly advised voting for men who shared his vision. He didn’t always win, but he always kept up the fight.

CityReviews

Books, movies, television and music of and about the city

Read more here.

According to a basic reference book, the mid-century Archbishop of New York had a fierce temper, but was also polite. Five feet nine inches tall, he had grey eyes, a Roman nose, brown hair and a resonant voice. According to John Loughery’s exhaustive, just-published scholarly biography, Hughes’ hair began to depart in his 40s, to be replaced by a toupee. Why would a bishop wear a toupee? This was a man who in many ways embodied the American dream. A member of an immigrant family, he worked his way up from a day laborer to an international religious celebrity who played a major role in making the American Catholic church and New York what they are today.

Loughery introduces the hero of his saga not in 1817 when the young man’s ship pulled into Baltimore harbor but on October 21, 1861, when Hughes received a telegram from William Seward, governor of New York, with a request from Abraham Lincoln. Would Hughes travel through Europe to “promote healthful opinions” about the Civil War? The cause was national unity, and the hope was that European nations would support the union cause, or at least not assist the rebels. He set out for London, Paris, Rome, Madrid and St. Petersburg. A highpoint was his hour-long chat with Napoleon III. After nine months and more visits, he came home, suffering from his arthritis and welcomed by some praise and much criticism, accused of going to Ireland to raise troops for Lincoln. For the first time in his climb to power he had to face self doubt—about his motivations.

A laborer with ambition

Our biographer turns the pages back to 1816-1818 as the seven members of the Hughes family made their separate voyages to Baltimore and looked for work. They had stopped paying for John’s education at seventeen, but, realizing that his American struggle demanded much more than that, John did construction work and made an arrangement with Mount St. Mary’s College, a Sulpician seminary in Emmitsburg, Md., where he would work on the grounds, live in a beat-up cabin and hope to be accepted as a seminarian.

He wanted to be a priest. At the time, however, he came across as merely a well-built, 22-year-old Irish immigrant ignorant of the academic demands on which the priesthood is built. So he was ignored by head-man Father John Dubois, who wished the young gardener would just keep his mouth shut.

Ordained October 15, 1826, John was sent to St. Joseph’s Church on Willings Alley in Philadelphia, where he lived with the bishop. Meanwhile John Dubois was named bishop of New York. At the time, Philadelphia was known for its street crime, labor unrest, two recent riots targeting black families and a mob burning down an abolitionist hall.

Hughes spent hours each week visiting the sick and teaching the young religion, as well as six to seven hours each Saturday hearing confessions. Hughes did not hesitate to tell friends that he had made 13 converts in his first months. He also delivered a very popular lecture on Irish identity; it was two hours long. Never having lived in a big city like Philadelphia before, Hughes began asking himself what it meant to belong to somewhat conflicting groups. Now in his late twenties, he concluded that “Irish American” meant three things, each in equal measure: Irish, American and Catholic.

A fight for control

With Archbishop Dubois’s health slipping, there was no surprise when Hughes was installed as his coadjutor with right of succession, now forty years old and sworn in at the old Saint Patrick’s Cathedral on Mott Street. This was the era in New York’s history when Walt Whitman called this “monster on the Hudson “one of the most crime-haunted and dangerous cities in Christendom” and the head of the Magdalen Society said he had 10,000 “girls on the town.” Twenty percent of the town’s 50,000 population were presumed to be Catholic, and the majority of them did not go to church.

Here Hughes was required to face perhaps the biggest problem of 19th century American Catholicism: the idea that a committee of laymen, trustees, should own and direct the parish church, hire and fire the priests. This was a Protestant idea, and Hughes would not permit it. Hughes’ stated position: Either the trustees relinquish their “rights,” or he would close the cathedral. One night 700 parishioners showed up to hear Hughes’ argument. Expecting an exchange of views, they got a searing diatribe, acting as if the trustees were not present. No one wanted the church closed.

Now for that seminary. Hughes bought the property on Rose Hill and hired a large group of Jesuits, who were closing out other apostolates, for a number of reasons. He needed a seminary to prepare young priests. He needed a college to educate young men. Though he may not have intended it, he created an intellectual center. Edgar Allan Poe, who lived a few blocks away, stopped by to converse with the priests. and distinguished guests, like Orestes Brownson, the transcendentalist philosopher and poet, a famous convert to Catholicism, was also a presence. Yesterday, I visited Brownson’s statue outside the university church, a colossal bust with the giant beard, like a cross between Karl Marx and Charles Darwin, a two minute walk from Hughes’ own statue.

Brownson, the principal speaker at graduation in 1856, talked of his faith that the United States and Catholicism would in the end be well suited for one another, known as the Americanization of the Catholic Church. Hughes was in the audience and stood up to speak when Brownson sat down. It was a harangue refuting Brownson’s ideas, putting the man in his place before a captive audience. The archbishop lost control of himself. Four years later Hughes wrote to Brownson warning him not to speculate that Catholicism was “especially adapted to the genius of the American people.”

‘Idiocy’ and honor

I’ll let John Loughery lead you through the final chapters of his brilliant story of this unusual, not-always- lovable but very important and often admirable man: his plans for building the new St. Patrick’s cathedral; the diagnosis of Bright’s disease and kidney failure that would kill him five years later; discussion of the “original, strong minded, superabundant intellect of the Irish peasantry; the bishop’s suggestion that slavery is wrong, but if the slave trader brought the unwilling captive into a Christian culture, we might deem the slave trader worthy of more than blanket condemnation (the “most perfect piece of idiocy ever penned” added Loughery); his condemnation of the 1863 draft riots.

Loughery includes his summary and critique of the other scholars’ evaluation, mostly negative, of Hughes’ career. The most distinctive difference between Hughes and several contemporary bishops is that Hughes would never simply reassign a pedophile priest. “John Hughes was no Cardinal Law.” My favorite line early in the book: “No one becomes a good writer who isn’t, sometime before middle age, an omnivorous reader.”

Raymond A. Schroth, S.J., author of nine books, is an editor emeritus of America magazine.