Ese Olumhense

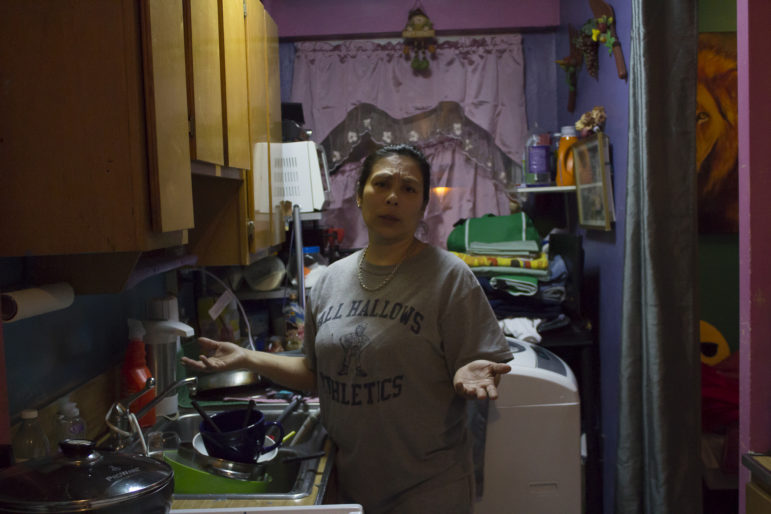

Gloria Castillo in her kitchen.

Castillo’s elderly neighbor, who declined to be interviewed for this article, remained in her building. Around the time she testified in the trial the second time, Castillo began her push for an emergency transfer. In support of her application, the Bronx D.A.’s office issued a letter detailing her participation in the criminal case, a key piece of documentation that intimidated witnesses are required to provide.

After denying her twice, saying they hadn’t received a police report from her — despite the fact that she did not need one as an intimidated witness and not a crime victim — NYCHA approved Castillo’s transfer request September 1, 2014, about 60 days after she applied.

Then began her long wait to receive an apartment offer. Despite many follow-ups from Castillo to NYCHA and the D.A.’s office — and appeals from her to politicians, social workers, Safe Horizon, and legal advocates — she waited almost a year and a half before getting an offer.

And that offer was for an apartment in Edenwald Houses, in which the NYPD has a satellite office to help monitor crime. Castillo refused it, fearing that it was too violent and would place her family further at risk. She detailed this and other concerns in a February 2016 letter to the Bronx D.A.’s office. “Edenwald Houses is not one of the safest communities, but in fact it holds one of the highest crime rates in the Bronx,” she wrote. Just two months after Castillo’s letter, 120 individuals from Edenwald and other nearby projects were arrested in a controversial “gang takedown,” then believed to be the largest in New York City history. Prosecutors said alleged gang members there “wreaked havoc on the streets of the Northern Bronx for years, by committing countless acts of violence against rival gang members and innocents alike.” Alleged victims included a 15-year-old child stabbed and “left to die in the street,” and a 92 year-old woman hit by a stray bullet at home.

Castillo was then offered a second choice, in the Boston Secor Houses, not far from Edenwald. Desperate, she went to see it the same day she got the offer, but was dismayed when a housing manager introduced a new requirement, telling her she would need to have one month’s rent and a security deposit in seven days, or she would lose the place. (That’s not how it works, NYCHA told City Limits. The agency requires the applicant to respond to an apartment offer within seven days, but the due date for any fees is only calculated after an applicant accepts the offer.) But she didn’t have the money and she was not allowed to move into the apartment. Her later efforts to find out why hit a dead end, with NYCHA ignoring her repeated requests to review her own application file.

Fearing the shooter would be released soon, Castillo pleaded to the Bronx D.A.’s office, begging for help with her transfer.

“What guaranties (sic) the secure safe stability for the children and I, in the event any retaliation from the criminal incarcerated is intended?” Castillo asked in her February 2016 letter.

Placing blame

Some, including City Councilmember Vanessa Gibson, chair of the City Council’s Committee on Public Safety, feel that residents who ultimately decide not to move into the developments offered them can’t totally blame their situation on the Housing Authority.

“I’m not saying it’s only NYCHA’s fault,” Gibson says. She also blames tenants who choose not to move to the apartments offered after being approved for transfer.

Yet others complain that the emergency transfer program gives applicants only the illusion of choice. There are fairly few low-crime NYCHA developments and they rarely have vacancies.

The agency’s oft-cited failure to promptly repair broken doors as well as hall and entrance lights makes its buildings attractive to criminals. At many sites across NYCHA, as at Castillo’s, entryway doors remain unlocked at all times, locks presumably broken by unregistered, or “off-lease,” tenants who live in the buildings. Lingering scaffolding, under which stealthy criminals can elude view, provides an ideal cover for crime.

Further, NYCHA has allowed violent criminals to live in its buildings, city investigators found recently, even when alerted to their tenancy by police. NYCHA, the audit found, failed to remove for tenants who are “knowingly sheltering dangerous criminal offenders,” bringing just 1 percent of these cases to a hearing for possible eviction in 2016. And by continuing to “allow criminals including gang members, drug traffickers and violent offenders to reside in public housing,” investigators wrote, NYCHA failed to protect the “overwhelming majority of law-abiding public housing residents.” The audit, as well as the process of “permanently excluding” whole families to ensure an individual convicted of a crime is barred from housing, are both controversial. Some legal aid advocates contend that permanent exclusion can have devastating consequences—including homelessness—for the families of people accused of crimes.

Crackdown on crime shows some promise

In the past three years, NYCHA has made strides in reducing violence in the 15 high-crime developments that were selected to participate in a crime-reduction program that Mayor Bill de Blasio announced in 2014. The developments selected for the Mayor’s Action Plan for Safety (MAP) were those that accounted for nearly 20 percent of all violent crime in NYCHA housing — Boulevard, Brownsville, Bushwick, Butler, Castle Hill, Ingersoll, Patterson, Polo Grounds, Queensbridge, Red Hook, St. Nicholas, Stapleton, Tompkins, Van Dyke, and Wagner. The $210.5 million, multi-agency effort provided additional funding for sidewalk lighting and cameras, increased police presence, and more activities for youth and families.

Since 2014, the mayor’s office said, violent crime has decreased 2.2 percent in those developments. Shootings in the MAP 15 are also down nearly 15 percent.

“Crime is down,” says Patricia Hardy-Wiltshire, who supervised the resident watch program at St. Nicholas Houses in Harlem. “And we haven’t had any shootings recently,” adds Hardy-Wiltshire, who has lived in St. Nicholas Houses since 1962. “St. Nick is very safe.”

Others worry that MAP, which only targeted a handful of developments, invested too much money in a program that is too expensive to replicate in the more than 300 NYCHA developments not covered by the initiative, which account for 80 percent of NYCHA crime. Some MAP developments, according to data obtained by City Limits, still produce the most emergency transfer applicants each year. In 2016, Castle Hill, Van Dyke, Polo Grounds, Patterson, and Boulevard Houses saw some of the most requests for transfer.

Asked how the city would expand its public safety goals across all of NYCHA’s developments, de Blasio said in February that the New York City Police Department’s neighborhood policing program, coupled with other “concentrated anti-crime strategies” like those deployed in MAP, comprise a “big sea change” that would reverse many of these trends.

One thought on “NYCHA Crime Witnesses Face Obstacles When They Seek Safety”

I have a son, & daughter-in-law, & numerous friends who work for NYCHA. I have observed from up-close the dangers, & hazards facing NYCHA employees DAILY, yet now, you expect them to continue to do the work with less resources, ARE YOU SERIOUS!!! NYCHA ranks right next to the Department of Sanitation as one of the dirtiest jobs, what with having to deal with vermin, (live & dead), vomit, feces, (of both the animal & human kind), toxic waste, filthy areas where they eat, having to enter into apartments that one would have to see to believe that tenants live in, drugs, etc. It is inhumane for both tenant & workers!!! As if that weren’t enough. we now have Mr. Ben Carson, who has been appointed to head NYCHA, who has absolutely “NO EXPERIENCE”, calling the shots. It’s demoralizing for the workers & adds “insult to injury”!!

Just picture for a moment, city without Sanitation, or, NYCHA to clean your filthy buildings?!! Let’s not forget that you are knowingly allowing tenants, calling special attention to children & animals, to live in inhumane conditions, allowing poor responses for repairs for months, while allowing politicians to lobby for gentrification, while tenants languish in filthy conditions. You are using re-zoning to displace hundreds, so, that you can sell them to the wealthy, who will receive all the financial assistance & convert these same filthy dwellings into beautifully restored apartments, complete with new trees, & playgrounds. Those poor living there currently apparently are not worthy of such treatment. You all forget, that God is watching & He Will Make It Right for All His Children!!