Ese Olumhense

In late 2012, Gloria Castillo’s neighbor, was shot in the lobby of their building. The senior citizen, struck on her way to church, stumbled down this hallway for help.

Gloria Castillo and her three children hated almost everything about living in their 21-story Bronx public housing building in the St. Mary’s Park Houses. The locks on their lobby doors were often broken, and the security cameras too, permitting a free flow of unauthorized visitors into the building. In her nearly 20 years there, the certified nurse’s aide and Salvadoran immigrant had filed dozens of requests for service for everything from the broken locks to a bedbug infestation that she and her family suffered twice to heaping trash outside her windows. She’d reported drug deals and drug abuse, attended community public safety meetings, and meticulously kept receipts, correspondence and pictures, all with the aim of one day getting her family out. Hoping that among the New York City Housing Authority’s (NYCHA) 325 other developments, she might somehow land in a better one, she had applied to move to a new building and was put on a wait-list in August 2013.

For months, she anxiously awaited her turn. When she became witness to a shooting in November 2012, her resolve to get out of St. Mary’s Houses became even stronger.

That brisk Sunday morning, around 10:30 am, Castillo was watching TV in her bedroom when she heard shots and ran to her window. Gunfire was a common sound, ringing out at least once a month, more often in the summer months. As she always did, Castillo got up and checked on her children. All were fine. But then, looking out at the building’s entrance below, Castillo saw an armed man running away. Shortly afterward, she heard screams for help from a person who appeared to be staggering up the staircase, and the thud of a body collapsing in the hallway in front of her second-floor door.

Recognizing the cries as her elderly neighbor’s, she rushed out to help. Against the pleas of her three young children, she opened her door, the only person on the floor to do so. There, her 67-year-old neighbor lay bleeding. Grabbing rubber gloves and her daughter’s much-loved “Dora the Explorer” towel, she worked quickly, removing layers of clothing and administering pressure while her son called 911.

Thankfully, the wounded neighbor lived. And the alleged shooter was arrested. But in the aftermath of the shooting, Castillo’s building wasn’t simply full of nuisances like bedbugs and broken locks — it was full of potential enemies. The alleged shooter and his family and friends lived in St. Mary’s Houses too, and Castillo would now be called upon to incriminate him. When she eventually testified at his trial, the shooter saw her face. Both of the 911 calls that she made were also played, allowing him and his associates to hear not only what she saw that day, but where she and her children lived, even her phone number.

Earning only about $15,000 per year limited Castillo’s ability to move. So, around the time of her June 18, 2014 testimony, Castillo asked the Bronx District Attorney’s Office to help her apply for an emergency transfer from St. Mary’s Park Houses. Designed to relocate residents who have witnessed or experienced certain crimes, NYCHA’s emergency transfer program offered Castillo what she thought would be her fastest route to a safer building. But there began what Castillo has since described as a “nightmare.”

An ever-present threat

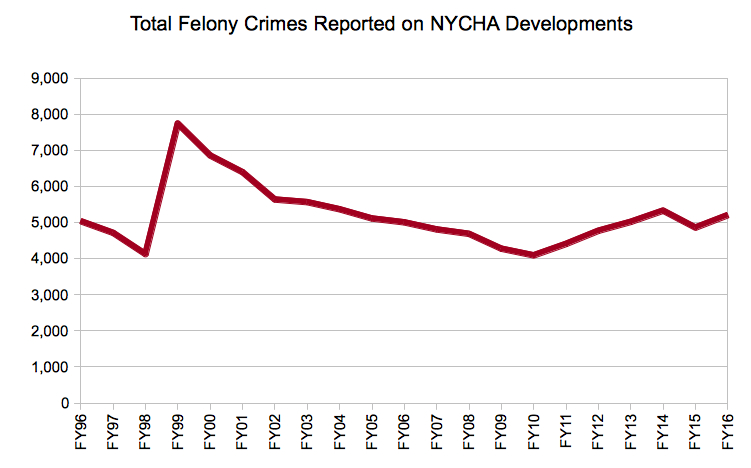

While violent crime has been steadily declining in New York City for the past couple decades, progress against crime in NYCHA has halted. After falling every fiscal year from 1999 to 2010, crime in NYCHA began rising again in FY 2011, and has returned to mid-1990s figures, according to a City Limits analysis of NYCHA data in more than two decades of annual reports. Nearly the same number of major felony incidents occurred in NYCHA in fiscal year 2016 as occurred there in fiscal year 1995: 5,205 incidents versus 5,266, respectively. The number of major felony crimes at NYCHA fell 2.32 percent from fiscal year 2016 to fiscal year 2017. The number of major felony crimes reported at NYCHA properties last fiscal year was still greater than it has been in nine of the past 11 years.

In February 2017, experts found that more than 33 percent of New York City shootings happen on or within 500 feet of NYCHA developments, and nearly a quarter of all reported New York City rapes happened within 500 feet or on a NYCHA campus.

That’s true “even though at best, or at most, public housing residents represent 10 percent of New York City’s population,” says Greg “Fritz” Umbach, assistant professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and author of The Last Neighborhood Cops: The Rise and Fall of Community Policing in New York’s Public Housing. “Statistically, you’re much more at risk of rape in public housing than you are elsewhere,” Umbach, who also works with NYCHA and the NYPD as a public safety consultant, tells City Limits.

After suffering from violence, thousands of NYCHA residents who have witnessed or experienced crime in their developments in the past 10 years have been transferred by NYCHA to a new development under the agency’s unique emergency transfer program. According to NYCHA data, more than 7,500 residents were approved for transfer between 2007 and 2015. In 2015 alone, 946 applications were approved for emergency transfer.

But a year-long City Limits investigation, which included interviews with dozens of NYCHA tenants, social-service providers, city officials, experts on NYCHA crime, and housing and legal advocates experienced with the program, as well as a review of almost a decade of emergency transfer program data, has found that many of the families who rely on NYCHA’s emergency transfer program are not getting the help they need.

A way out, for some

Administered by NYCHA’s Family Services department for nearly 30 years, the emergency transfer program is designed to help six categories of people — victims of child sexual violence, victims of domestic violence, victims of traumatic incidents and domestic violence witnesses, as well as other intimidated victims and witnesses of crime — move to a new NYCHA development after violent incidents in their current one.

NYCHA is one of a few large U.S. public housing authorities to offer this kind of program to residents who witness or experience crime. While housing authorities in San Francisco, Chicago, Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia and Los Angeles have similar programs, NYCHA is the only one nationwide that offers applicants additional help through partnerships with local social-service providers. With city rents climbing, there is a severe lack of apartments available to the the average NYCHA household, which earns $24,336. Most cannot afford to move after a crisis without the transfer program.

But for decades, many applicants who had proof that they had experienced crime were being denied transfers. Until mid-June, NYCHA required tenants applying under the category “intimidated victim” to prove, using police reports and other documentation, that they were victimized not only once, but twice within a one-year period, and in a “non-random” manner at the hands of the “same abuser or associate,” internal NYCHA management manuals and program forms obtained by City Limits show. Sometimes NYCHA showed applicants with one incident leniency and approved their transfer requests, advocates who have years of experience working with safety transfer applicants say. But without this proof, many transfer applicants were denied, these advocates contend. NYCHA denied more than half of the emergency transfer requests it received from applicants who reported being crime victims in 2015, a City Limits analysis of NYCHA data shows.

See a copy of NYCHA’s emergency transfer application form

See a copy of NYCHA’s emergency transfer application formThose who are approved for transfer often face long wait times to be placed in a new apartment afterward. The wait is on average three to six months, multiple advocates from Safe Horizon and Sanctuary for Families say. Both organizations work with NYCHA to assist program applicants. In July 2017, 256 families who had already been approved for a transfer were on NYCHA’s emergency transfer waiting list, including one family who had been waiting for an emergency transfer since March 2012, data obtained from NYCHA shows.

Families that stay on the waiting list a long time are likely hard to place because they are very large or very small family sizes, which don’t fit the majority of the vacant apartments. A 2015 audit, however, found that NYCHA lacked a rigorous system of monitoring its vacant apartments, and as a result didn’t have a clear sense of where it could place the more than 250,000 families waiting for housing in any of its developments. Hundreds of vacant apartments went unoccupied — some for up to a decade — while crime victims lived in fear. In a written response to the audit, NYCHA agreed to implement a better system of tracking vacancies, but said they didn’t have the funding to expedite repairs on the unoccupied apartments. At present, NYCHA reports that its average turnaround time for vacant apartments hovers at 50 days, well above its 30-day target.

Additionally, many victims are presented with relocation options in areas that are more dangerous than the places they are trying to leave, leading some applicants to decline NYCHA’s offer and stay put, says Maureen Curtis, a vice president at Safe Horizon, one of two nonprofits that works with NYCHA to help crime victims apply for transfer. She’s worked with program applicants for almost 30 years. Once given an offer, a household is allowed an opportunity to refuse it, then receive a second and final offer, which they can also refuse. By the end of that process, less than half of the crime victims approved for emergency transfer actually end up transferring, says Curtis.

“Often times, when people turn [transfer offers] down, they turn them down because they’re not in a nice area,” Curtis says. “And I totally understand that. If I’m fleeing my home because of violence in the home, and now I’m going into an area where maybe there is high crime, I won’t want to go into that area. Some developments you’re reading about in the news, and these are ones that people could be getting apartment offers in.”

Transfer applicants can file an administrative grievance concerning a transfer decision. And, according to Rajiv Jaswa, a staff attorney at the Urban Justice Center, a legal services organization in New York City, those grievances can prompt a review by NYCHA borough management or a hearing. But it is hard to file a grievance or be heard when you do, says Jaswa, who began his career working with NYCHA tenants. Some grievance filings — including those unrelated to emergency transfer — simply get ignored, he says. Some years ago, when he and his colleagues held legal clinics in and around NYCHA developments to help residents file grievances related to a variety of housing issues, Jaswa says he found that many grievances he submitted never received a response, despite follow up.

Even as crime rises in NYCHA, the number of tenants applying for transfer has been decreasing. Requests for emergency transfer have been on a mostly downward trend since at least 2007, declining for all five categories of transfer for which NYCHA supplied data.

One thought on “NYCHA Crime Witnesses Face Obstacles When They Seek Safety”

I have a son, & daughter-in-law, & numerous friends who work for NYCHA. I have observed from up-close the dangers, & hazards facing NYCHA employees DAILY, yet now, you expect them to continue to do the work with less resources, ARE YOU SERIOUS!!! NYCHA ranks right next to the Department of Sanitation as one of the dirtiest jobs, what with having to deal with vermin, (live & dead), vomit, feces, (of both the animal & human kind), toxic waste, filthy areas where they eat, having to enter into apartments that one would have to see to believe that tenants live in, drugs, etc. It is inhumane for both tenant & workers!!! As if that weren’t enough. we now have Mr. Ben Carson, who has been appointed to head NYCHA, who has absolutely “NO EXPERIENCE”, calling the shots. It’s demoralizing for the workers & adds “insult to injury”!!

Just picture for a moment, city without Sanitation, or, NYCHA to clean your filthy buildings?!! Let’s not forget that you are knowingly allowing tenants, calling special attention to children & animals, to live in inhumane conditions, allowing poor responses for repairs for months, while allowing politicians to lobby for gentrification, while tenants languish in filthy conditions. You are using re-zoning to displace hundreds, so, that you can sell them to the wealthy, who will receive all the financial assistance & convert these same filthy dwellings into beautifully restored apartments, complete with new trees, & playgrounds. Those poor living there currently apparently are not worthy of such treatment. You all forget, that God is watching & He Will Make It Right for All His Children!!