DOENYC

District 3 in Manhattan

When my kids entered kindergarten on the Upper West Side, a half-taboo conversation was whispered down the hallways. Almost everyone was white, and even more were fairly wealthy. Like me, they had opted for public school for two reasons: they couldn’t stomach paying hundreds of thousands of dollars for private school when public school is free, and they wanted their kids educated in a diverse setting. But the school was not diverse at all. It was much whiter and vastly wealthier than the surrounding neighborhood. Compared to the district as a whole, it was even wider of the mark.

Talking about the missing kids was incredibly touchy. A few parents formed a committee to ask simple questions like “what’s going on here?” and “how can we help?” Moving tentatively, we started with race rather than income. But many parents and school administrators really didn’t want to discuss it, especially the race of children. They groped to describe it in any other terms. In one painful conversation it came out as “kids of different… nationalities… I mean, backgrounds… experiences…” In another, someone pointed to Jewish and French-speaking families as evidence enough of diversity.

These kinds of talk-arounds helped the school resist change. Administrators labeled “unfair” some of our basic requests to address how admissions and school life work against Black, Spanish-speaking, and low-income families. One example: the school initially refused to translate notices into Spanish (the primary language of the neighborhood, after English) saying that speakers of other languages might be offended. The same year only 5 of 100 kindergarteners were Black, and the school put one in each class. In hallway discussions, often whispered, many parents of color were appalled. But the cost and stress of raising race as an issue weighed against the urgency of objecting, and no one did. For this article I spoke to parents who stayed at the school after my kids transferred. Some said that more parents are now talking about diversity in general, but many still fear raising specific issues; for example, concerns that the school deals more punitively with students of color and less collaboratively with their parents.

The conflict over diversity was head-shaking. But it turned out that it had been ongoing for years. In 2004 the Center for Immigrant Families collected and analyzed low-income families’ experiences of discrimination, including at our school. As my kids entered school, the Parent Leadership Project was still raising it, and had just created the District 3 Task Force for Equity in Education, which I later joined. Even so, parents like me had continued to send kids there seeking diversity. (Other parents seeking a mostly-white school had also found it there, attesting to our short-sightedness.)

How could well-meaning parents continually be so wrong? Well, here’s how it happened to me: I opted for public school on principle. And again, it’s free. But I wasn’t going to sacrifice my children on the altar of a failing system. So I scoured websites and reviews to find the “good schools.” My zoned school was never on the list. When I found the right one, I assumed we’d be waitlisted because we had no right to a seat. To get my kids in I used connections, stalked administrators, showed up at school events. If there were things I didn’t do – volunteer for PTA fundraisers or whatever – it’s because they were too nuts for me to think of. Even as I used all my privilege to advocate, I assumed that families who got seats the regular way would look like the neighborhood.

What I hadn’t accounted for was that, in fact, there is no “regular way.” Instead, there are two separate school systems. One system is zoned schools, where kids are assigned to schools near their homes, and they attend. That’s for poor kids. (Wealth and race are closely linked in NYC.) The other is the shadow system with no name, where parents choose the school they want their kids to attend and advocate six ways to Sunday to get them in. Sometimes they move close to the school, often straining their budgets, and use the zoned school system to claim a spot: you could call that buying in. Sometimes they just get on the waitlist and call, volunteer, donate, or pull strings. If forced, they do kindergarten at a school they don’t want, then switch.

That unnamed system is for wealthy, well-connected, or privileged families. The shadow system is so shadowy that it’s hard to define exactly who accesses it, although the Center for Immigrant Families report lays out its complex operations. Wealth helps, but families with modest incomes use it: plenty of artists, for instance. Education and familiarity with bureaucracy helps, as does a strong sense of entitlement. Being white helps, but it’s not required. And it’s easier to access sought-after seats if you’re a “good fit”, which often means fitting into a privileged, mostly-white environment.

This is no exaggeration. Families privileged in this way choose their schools. Other families – broadly, low-income families – don’t have the same choices. There are exceptions, but those are the systems. Privileged families don’t send kids to low-income schools unless they’ve chosen to. With few exceptions, they only choose low-income schools where they can get seats in Dual Language, Gifted and Talented, or other special programs; they don’t throw in their lot with a low-income Gen Ed program. When families like mine make our well-intentioned entry into the public school system, we’re actually pushing aside low-income kids aside twice. That’s because we’re not entering the same system.

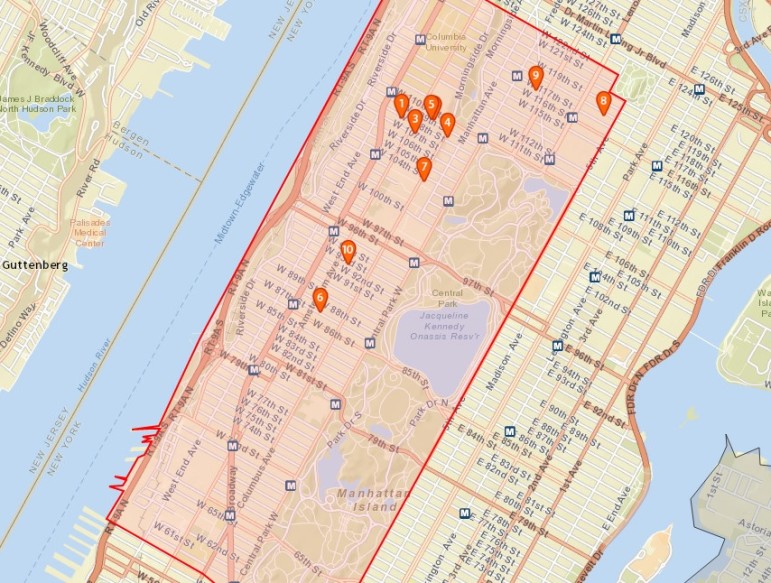

The reason I hadn’t accounted for two separate school systems is the myth that insists there’s one system for everyone. That myth is demolished when you look at District 3, covering the Upper West Side and part of West Harlem. It’s a mess. Our schools are deeply segregated (some marked “apartheid schools” in a much-cited UCLA study) by families’ income, race, and national origin. Gentrifiers move wealth uptown, but they don’t send their kids to local schools.Poor schools lose basic funding through budget cuts and kids fall behind, while in rich schools PTAs raise a million dollars to fill gaps and add enriching programs. The “rich schools, poor schools” rift is so deep that sometimes it’s hard to believe we’re talking about public schools. Maybe we’re not: the Times labelled the wealthy ones “public private schools” in 2012.

The myth of a single school system is kept alive by policymaking ostensibly aimed at making schools fairer. Often, efforts to address segregation suggest to parents that New York City’s difficult housing market is to blame. Since that seems intractable, segregation does too. Or it invites discussion of bussing, which is the surest way to shut down a conversation about equity. (We don’t need bussing to fix this.) For instance, CEC3 spent 2014-2015 wrangling over a few high-income schools that have become overcrowded. Many families moved there at great expense specifically to access a well-resourced school – in other words, to take advantage of how segregation has allowed some schools to beat budget cuts by concentrating wealthy families. But the CEC and DOE treated it mainly as a housing and neighborhood problem, rather than looking at why people didn’t want to live (more cheaply) near other schools. As it happened, there was space in a mostly low-income school nearby where wealthier parents refused to send their kids. But many parents, including CEC members, continue to insist that schools are segregated because neighborhoods are.

Another example came a year later. DOE announced a pilot program in 7 schools where seats would be set aside for low-income kids. Some are in gentrified Brooklyn neighborhoods where low-income families have famously been priced out by the Mamarazzi. But most are actually in neighborhoods where the median income is low enough to qualify for free lunch. If those schools are colonized by wealthier families, it’s because of the dual school system, not a lack of low-income kids nearby. But without acknowledging that there are two separate school systems, it just looks like DOE is fixing an imbalance created by gentrification.

Under pressure from advocates and parents, CEC3 held two Upper West Side forums in March to discuss Community-Controlled Choice, the kindergarten admissions policy that would make each elementary school approximate the diversity of the district. It’s a good start, but the CEC still hasn’t made school equity a concrete goal, nor set up a process to hear from low-income parents. More importantly, the CEC broadly denies the existence of the dual school system.

The mystery of how privileged but diversity-seeking families keep ending up at “private public” schools is cracked. We drank the Kool-Aid that we were living out our principles by sending our kids to public schools, because the uglier truth is constantly papered over (and maybe because it worked for us.) Faced with the reality of a separate and unequal system, will privileged parents will want to do something about it? I’m optimistic that they will. That’s one reason that Community-Controlled Choice is gaining momentum. Parents exhausted by the scramble for kindergarten, and disgusted at the dual system, are excited by an admissions policy that doesn’t give privilege any power – and makes sure public schools are really for all kids, as we’ve been promised.

Parents do need the DOE and CECs to take up desegregation and equity, we can’t make the change entirely by ourselves. But moving the starting point of the conversation from destructive myth to reality, so we can actually address the problem? Parents can do that.

* * *

Emmaia Gelman is a member of NYC Public School Parents for Equity and Desegregation (www.nycpsped.org). It’s a new group uniting parents from “private public” schools, “public public” schools, and not-yet-in-school-kids.

7 thoughts on “CityViews: Addressing School Inequities Means Admitting There’s a Shadow System for the Rich”

DON’T BE STUPID CITY LIMITS………there is no such thing as white flight parents saw the next generation of kids on a Jail track and not a college one and moved…guess what blacks did too!!!

What’s so bad about having schools that the middle and upper classes want to send their kids too? Middle-Class flight could happen again.

or think about it backwards….are inner city kids born inferior? if not then the only difference between a good school and a failing one is…the good school forces you to speak English when you enter the building

No one is born inferior. The truth is that even so-called ‘progressive’ parents won’t send their kids to a school with large numbers of troublesome students. Look how some want to water down NYC’s superb specialized high schools.

exactly so why are black people always bitching about poor schools? if they are not inferior than its personal choice to be ghetto, gangsta, illiterate and in jail….right?

Shut your dumb racist ass up.

is that all you can say??? how is it racist? explain it to all of us…….