Peter Stehlik

These days, fewer things burn, but fire trucks make more runs.

Fire Commissioner Daniel Nigro will unveil a plaque on Monday at the statue of the kneeling firefighter on 43rd Street as the department continues the commemoration of its 150th anniversary year. The statue eerily arrived in New York City on its way to Missouri two days before September 11 but never left because it became a memorial to the steep sacrifice the FDNY made at the twin towers.

Fourteen years later, it stands a reminder that for all that’s changed since the Metropolitan Fire Department formally took over fire protection in New York on August 1, 1865, firefighters still face unique and serious risks, whether at a catastrophic disaster scene or in a run-of-the-mill attic fire. City Limits reported four years ago on lessons learned from FDNY line-of-duty deaths before and after the World Trade Center attack. One clear takeaway was that no matter how few fires there are, the city will need people who know how to extinguish them, who are willing to rescue people from them and who are close enough to get there in time.

Still, it is striking how few fires there are these days. According to Terry Gorman’s masterful history of the FDNY, So Others Might Live, there were 153,000 fires in 1976. By 1993, the number had dropped to 94,000. Last year, there were just over 42,000 blazes—most of them not in structures.

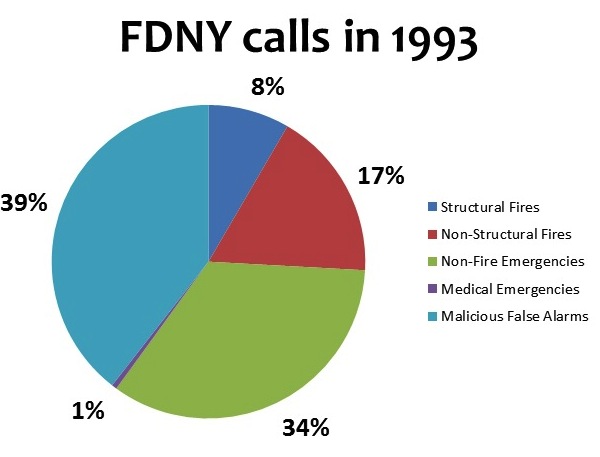

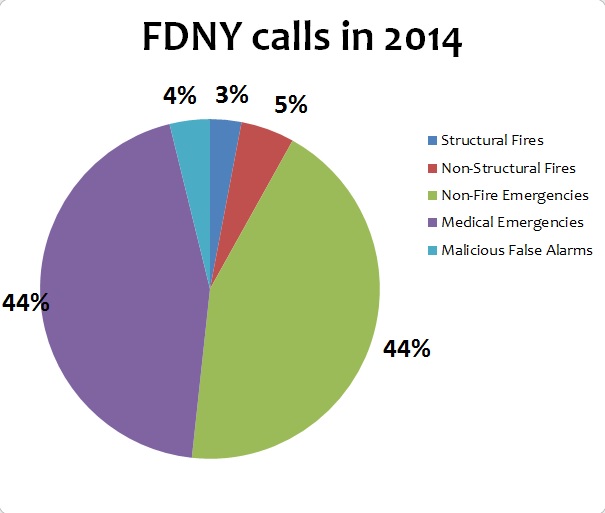

Yet 2014 stands as the busiest year on record for FDNY, with 520,000 calls—43 percent more than in 1993. The divergence of fire numbers and FDNY business can be chalked up to the huge rise in medical emergencies to which firefighters responded. In ’93, fire companies logged just under 2,000 medical emergencies; last year there were 226,000 — a 116-fold rise*. The number of calls under the separate category of non-fire emergencies, which includes stuff like gas leaks, has also soared, leaping 84 percent over the past two decades. (You can get all the FDNY and EMS stats you want here. The huge decrease in malicious false alarms is also noteworthy.)

As Gorman notes, fire companies had long responded to medical and other non-fire emergencies: “In the social chaos of the 1960s and 1970s, New Yorkers learned that the quickest way to summon medical assistance was not bt calling for an ambulance but by calling the Fire Department.” When he took office in 1994, Mayor Giuliani sought to formalize and expand that role. With the number of fires dropping steadily, the FDNY looked to the budget-conscious mayor like abundant first-responder talent with a shrinking workload. In 1995, against some resistance from both parties, Giuliani proposed merging FDNY with the city’s emergency medical service. In March of ’96, Nigro was sworn in as the first chief of the new FDNY EMS.

Since then, fewer things burn, but fire trucks make more runs. The merger was, one FDNY official once told me, “a job saver.” And for people who’ve benefitted from the :32 second improvement in response to medical emergencies since 1993, it’s probably been a life-saver, too.

*CORRECTION: The original version of this story misplaced the decimal point, reporting this figure as 116 percent. In fact, it’s more than 11,600 percent.