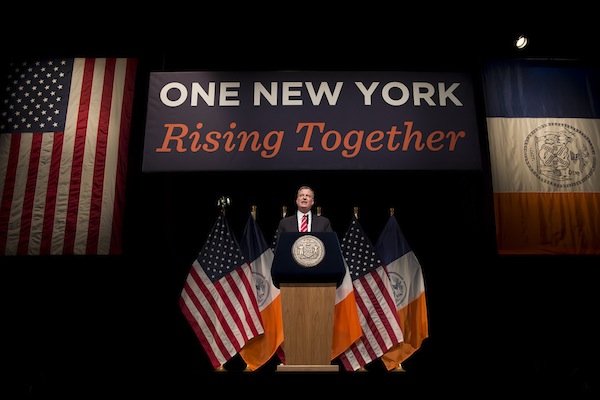

Photo by: NYC Mayor’s Office

Mayor de Blasio’s recent resounding electoral victory proved that his “tale of two cities” rhetoric struck a chord with New York; his vision of a just, accessible, and united New York City offered hope for the future. But in order for the city to actually “rise together,” it is not enough for de Blasio to simply enact his own policy agenda (however challenging that might be). The mayor needs to re-engage the public in the local political process, empowering citizens to solve problems in their own communities. And it’s worth the mayor starting with promoting a population that has systematically been excluded from the political process: our young people.

This election’s record-low turnout (a paltry 24 percent, the lowest seen since the mid-20th century) has been written about ad nauseam. While many ascribe the low participation to the expectation of de Blasio’s decisive win, it’s clear that New Yorkers are part of a nationwide trend of decreasing political engagement. While we can trace much of this to fallout from the gridlock and dysfunction of our nation’s capital, some of it stems from New York City. In addition to more bike lanes, less sugar consumption, reinvigorated park spaces, and a robust charter school sector, the Bloomberg years leave us a political reality in which constituents have effectively been removed from the equation. Bloomberg deftly navigated the bureaucracy’s hallways in efforts to independently enact his vision for a vibrant New York, but avoided engaging people in this process. De Blasio, a former organizer and local school board member, positions himself as a voice of the people, committed and eager to pursuing the causes of working New Yorkers. But he needs to move beyond populist symbolism.

More than serving as a voice, Mayor de Blasio should use his authority and influence to promote all voices, not only incorporating citizens into the conversation but guaranteeing that all of New York’s residents are able to continue to advocate for themselves and their communities long after after he leaves power.

De Blasio’s fight to expand pre-K opportunities demonstrates such a long-term investment, but in order to “lay the foundation now for the strength and stability of New York’s future,” words spoken during the mayor’s first State of the City, we must teach young people not just to be college- and career-ready, but also, to be citizen-ready.

This will not come easily. For many reasons, including the rise of standardized testing and the stipulations of No Child Left Behind, civics education has been largely pushed out of schools’ curricula. Yet, the Commission on Youth Voting and Civic Knowledge, in a recent report, acknowledges that even a strong civics education program is no silver-bullet solution for increasing youth participation – an effective approach must be multi-faceted. Recognizing this need, a diverse coalition of local youth-serving organizations has come together to urge the mayor to make youth civic engagement a priority in his vision for New York’s future. The coalition has outlined five specific actions, directed at both the municipal and state levels, to increase youth political participation, In order to promote youth political engagement, de Blasio should:

1) Use his authority and influence to focus on the importance of increasing youth political participation: De Blasio should use his position as mayor to make the case for the importance of youth political participation. As a former community organizer, he is keenly aware of the importance of citizen involvement in the political process. He could focus an early mayoral speech on the importance of youth political participation,.

2) Ensure that civics education is further incorporated into school curricula: Civics education should serve as a great equalizer, equipping all students with the knowledge and skills to effectively participate in their communities. As of now, this is not the case. Currently, city students are only required to take a one-semester, widely underutilized, Participation in Government class. As de Blasio and Schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña consider priorities for reforming the city’s education system, they should make civics education a priority.

3) Support lowering the voting age to 17 in local elections: The town of Takoma Park, Maryland, recent lowered the voting age to 16 for local elections. This act ensured that young people would be educated about voting, and encouraged to vote, while they were still in school, whereas most young people have graduated (or dropped out) from high school by the time they are of voting age. The act resulted in 44 percent of registered 16- to 17-year-olds voting in the recent local elections, compared with 11 percent of the overall town electorate. Supporting lowering the city voting age would demonstrate a commitment to youth political engagement and undoubtedly stimulate a national conversation on the topic.

4) Advocate for a bill allowing 16- and 17-year-olds to serve on community boards: Throughout New York City, community boards allow everyday citizens to participate in and help guide the political process, addressing zoning issues and other neighborhood concerns. The State Assembly and State Senate are considering bills (A02448 and S04142) that would allow 16- and 17-year-olds to serve on their local boards. This would allow young people to make their voices heard in the city, while also giving youth ownership over local issues. It would benefit communities by incorporating the voice of a larger percentage of local residents, by affording boards a direct outlet to advertise initiatives to young people, and by training the next generation of community leaders and advocates.

5) Support voter pre-registration legislation: The New York State Assembly and Senate are considering legislation (A02042 and S01992) that would allow 16- and 17-year-olds to preregister to vote, following the efforts of over a dozen states that have successfully passed similar bills. With only 46 percent of eligible voters between 18 and 24 years of age registered to vote as of the 2010 census, this change would ensure that more young people become both registered and educated in schools on the importance of voting, before they graduate.

In his 2009 run for Public Advocate, de Blasio emphasized that he wanted “to make sure the people are never kept at arm’s length from their own government,” and it’s clear that this philosophy has guided him throughout his organizing and political career and into Gracie Mansion. Mayor de Blasio and his administration can offer clear, bold leadership and take decisive action to move engaging New Yorkers in the political process beyond a sound bite and into reality. Perhaps one of de Blasio’s strongest legacies could be a New York City re-engaged in its local government. That starts with young people.