Photo by: Pratt Center

Oen proposed route would go from Sunset Park to JFK through southeast Brooklyn neighborhoods cutting a 90-minute best-case transit route to 75 minutes.

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), according to a policy proposal from then-mayoral candidate Bill de Blasio, “has the potential to save outer-borough commuters hours off their commute times every week and stimulate economic activity in neighborhoods the subway system doesn’t reach.”

Eight new proposed BRT routes, including two linking the Sunset Park industrial waterfront to points east, could have even more impact: making jobs available to potential employees who’ve been gentrified out to transit-deficient neighborhoods, said Joan Byron, Director of Policy for the Pratt Center for Community Development. The Pratt Center, in collaboration, with the Rockefeller Foundation, recently

nominated eight potential routes for BRT.

Businesses in Sunset Park could benefit. “We do know from our industrial work,” Byron said, “that access to the area is a significant barrier to companies locating or growing there.” The waterfront-area industrial zone, which has nearly 33,000 jobs, already draws many workers from nearby residential areas, as well as others who comfortably commute, but still has significant vacant space and opportunity for expansion.

The goal of BRT, Byron observed, isn’t just to speed trips for current commuters, but also “to enable people to reach destinations they now can’t realistically get to.” Neighborhoods in south and east Brooklyn, far from subways, now often have multigenerational households; even if they do have a car, she said, it can’t be used by multiple wage earners.

“Creating better access to get employees here is always a good thing,” observed David Meade, executive director of the Southwest Brooklyn Industrial Development Corporation, when asked to comment. “Our employers are always looking for good people. It would be a good thing for employers they have a wider net.”

Getting to BRT

The proposed corridors were selected based on their potential benefits—connecting job centers and healthcare/educational hubs with areas where many people live more than a half-mile from a subway station—as well as corridors where BRT is feasible, meaning streets with six or more traffic lanes, center medians and long distances between intersections.

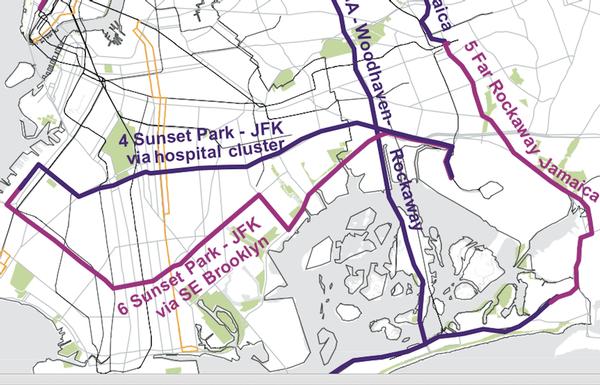

One route, among four “first-tier corridors,” would go from Bush Terminal/Industry City at 37th Street and Third Avenue to John F. Kennedy airport through the job-rich hospital cluster around Flatbush, then Brownsville and East New York. The report estimates that route would cut the current 55-minute commute—in a best-case scenario—to 21 minutes, a 62 percent improvement.

Moreover, the circular route would link to subway lines, fostering faster trips. Among those who could benefit are more than 7,800 people living in Brownsville and East New York public housing, currently far from subway lines.

The Pratt report, “Mobility and Equity for New York’s Transit-Starved Neighborhoods: The Case for Full-Featured Bus Rapid Transit,” lists four second-tier corridors—which have fewer wide streets and may already be densely built up—for a second phase.

One route would go from Sunset Park to JFK through southeast Brooklyn neighborhoods like Gravesend, Flatlands and Canarsie, as well as Queens neighborhood near the airport. It would cut a 90-minute best-case transit route to 75 minutes.

While that 17 percent improvement may seem relatively modest, even relatively modest changes may be helpful. Some 36 percent of workers who live in the community districts along this corridor must travel an hour or more to their jobs.

Next steps

BRT would be more costly and more difficult to implement than the current Select Bus Service, which lacks physically separated lanes.

But Pratt urges “real BRT,” so it sought corridors with wide streets and medians. Not only could this bring much faster bus service, it could build safer streets as corridors are redesigned to curb speeding and dangerous turns.

BRT, said Byron, “isn’t going to happen if stakeholders in community don’t want it to happen,” so the next step is to test the ideas with constituents, mindful of potential challenges like conflicts with other uses of the street.

But if de Blasio does create 20 new routes as promised, industrial neighborhoods like Sunset Park would benefit. BRT isn’t cheap—perhaps $100 million per route—but, compared to the cost of a new subway, it’s hugely more affordable.