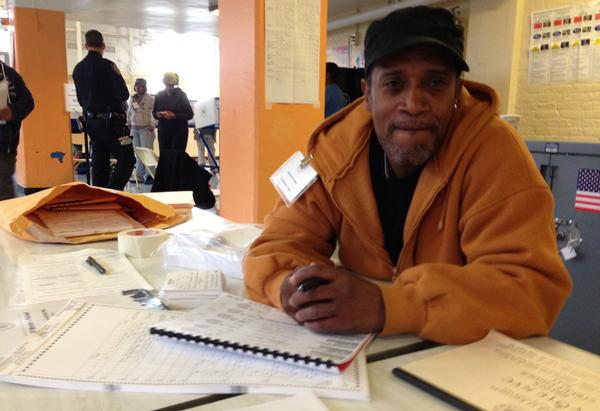

Photo by: Oliver Morrison

Poll worker Anthony Cooke maintains a Republican voter registration chiefly to facilitate getting work on election days. But he also always votes, because people died for that right.

Phyllistine Woods was manning the front desk of P.S. 6 on Tremont Avenue on Election Day morning, a little more than an hour after the polls had opened. She was working on a crossword puzzle from the National Enquirer.

15 feet to her left, Helene Jones, one of the West Farms polling station’s two site coordinators was on the phone with the Board of Elections. The third of only three electronic voting machines had just jammed and a line of voters was starting to build up.

The board told Jones to break the seal of the machine in the presence of a police officer and fix it.

“I had to do it or they would have all had to use emergency ballots,” said Jones. “I did get kind of nervous.”

Jones’s repair worked. The moment was just one of many on a day at PS 6 that was a study in the contrasts of democracy on Election Day. Workers and voters exhibited both extraordinary civic pride and narrow self-interest. It was frequently tedious but occasionally tense.

“The trio”

The polling place was located inside a small gymnasium, filled with cafeteria tables, fluorescent lights and a handful of silver refrigerators that hummed during the 16 hours the polls were open.

As voters entered they gave their home address and then were sent to one of the tables that represented each voting district, staffed by three poll workers each.

Near the entrance to P.S. 6 the poll workers Evelyn Furgusion, 51, Robin Dixon, 53, and Anthony Cooke, 57, reclined in their chairs and joked for much of the day. Not many voters came to their table.

“They need to pay us more,” said Dixon.

“They shouldn’t take our tax money out of it,” said Furgusion.

“You gotta know what to write. I put exempt,” replied Cooke.

They said they got paid $200 for the day, plus $100 for a training they had to do before.

“I like it when it’s busier,” said Dixon. “It’s too long of hours to be sitting here doing nothing. I like getting tired.”

“I like it when it’s slow,” said Cooke.” I don’t care if anyone comes. It’s all the same to me.”

Dixon explained the reason for their friendly banter. She said, “We’re the trio. Every election we’ve been working together.”

Cooke said that he originally registered as a Republican during the first Bush administration because he thought it would give him more power with elected officials. But now he keeps his Republican status, despite voting for Democrats, because he knows it means he is more likely to get a job at a polling site.

“You ever seen three black Republicans?” he said.

But while Cooke acknowledged his self-interest in wanting the job and maximizing his pay, he also was quick to move a table to help an elderly woman pass by and also to assist voter Ronald Hill, 70, read the small print in the ballot.

“You take that magnifying glass, you’re gonna need that,” said Cooke.

And Cooke said he always votes.

“I vote because people sacrificed their lives to give me the privilege to vote. The people in the Civil Rights movement, took a lot of lumps and bruises,” said Cooke, whose mom is Puerto Rican and father West Indian, but who identifies as black.

“This is the easy job. What have we been doing all day? Shooting the shit,” said Cooke.

Frustration at other tables

But at the table right behind “the trio” things didn’t go as smoothly. Sandra Tyler, 47, arrived at the polling site several hours after the polls opened, as an alternate. She said at first she wasn’t on the same page as the two other workers at her table.

“Stop licking the pages,” said Deidra Hall to Tyler. “I can’t work with people who lick the pages. That is so nasty.”

Then Hall showed Tyler how to rip off the ballots without tearing them. Several voters had been returning for new ballots because the machine wouldn’t accept them.

“The perforation of these new ballots is not perfect,” said Tyler. “The old ones it was simple, one, two, three.”

By the end of the day Tyler said, during a smoke break outside, her table had managed to get all of their papers back in order.

“You can’t have three people doing three different cards at the same time.” Because her table had to issue a new ballot to some voters, they had issued more ballots than voters but hadn’t been able to get the numbers to match up.

Tyler’s table also had more than three times as many voters as Cooke’s table.

“When you have more voters, you want to keep the line moving because you don’t want people getting frustrated and walk out,” said Tyler.

At a table in the very back of the gym, Hazel Williams, 82, read the Daily News, while Ellen Anderson, 41, complained that the cafeteria seats weren’t comfortable for a worker like her.

“I’m over 200 lbs. I’m scared to sit on that chair,” said Anderson. She brought a pillow to sit on and refused the plastic chair Williams sat in.

The third worker at their table, Katrina Rawlins, was one of the few who were missing their regular jobs to work the polls. Many at PS 6 were retired, on disability or collecting unemployment from seasonal work.

Rawlins was using one of her vacation days as a hospital administrator, which she normally uses to travel to places like Costa Rica. And while most said they were going to bed when they got home, Rawlins said she was going to stay up to watch the election returns.

The voters

Edgardo Ortiz, 43, showed up at a voting table in the back of the gym with his 9-year-old son, Edgardo Jr., translating for his father. Ortiz said his wife, who usually accompanied him, was at home sick.

But a minute later Ortiz Jr. returned to the table and asked if there was another ballot in Spanish that his dad could read. Poll worker Dorothy Zimmerman said that “that was just how the ballots were.” Another poll worker told Ortiz Jr. to ask the site coordinator.

Ortiz Jr. walked back to his dad in the voting booth and appeared to translate the ballot for him.

After much confusion, voter Juanita Baez, 58, was told to fill out an affidavit ballot because, though she has a mailing address in the Bronx, she lives in a shelter in Manhattan. Baez said she came to the same polling station the year before, after Hurricane Sandy, and didn’t have any problem.

Voter Jorge Santos, 55, who said that his father once served on the City Council, came in wearing a fedora and a Tennessee Titans jacket, chatted with poll workers and broke the news that there had been a major accident on Washington Avenue.

“Somebody’s car bumper is up on a tree right now, that’s how hard the impact was,” said Santos.

Tyrone Wright, whose job it was to relieve other poll workers when they went on break, said that most of the voters had been elderly.

“These old folks don’t miss nothing,” said Wright. “They come out with their home attendants. They make their kids come out and their grandchildren.”

With the rush comes tension

When poll workers Dixon and Furgusion returned from the Chinese buffet down the street, they slouched back in their chairs.

“I ate everything,” said Furgusion.

“That’s why she’s sleepy,” said Dixon.

But as the slow, repetitive work at midday started turning into evening, people’s frustration grew.

“Tony. Tony. Tony,” said Dixon across the room to Cooke, who was helping someone else out. “We are eating your cheese doodles.”

When Cooke returned he wasn’t in a joking mood.

“You don’t go through my stuff. I wouldn’t go through your purse,” said Cooke.

Their earlier banter turned more serious and political.

“They already shut down the government,” said Dixon. “Now they’re cutting people’s food stamps.”

“That has nothing to do with the mayor,” said Cooke. “That’s the senators.”

“They want to cut the deficit but they always want to take it from the poor,” responded Dixon.

“The poor are the deficit. They’re the one that want the benefits,” said Cooke.”

“It’s Wall street…” said Dixon.

“Look, kids graduating from Princeton and Harvard can’t get jobs either,” said Cooke.

While Cooke and Dixon were talking, Furgusion was on the phone. “Baby, I’m so tired you don’t even know. I can’t wait to get out of here.”

When the site coordinator told them they needed to sign their affidavit ballots into one of their booklets, they seemed annoyed.

“We didn’t have to do that last time,” said Cooke.

“They change things every year,” said Dixon.

Even the police officer on the scene, Glenn Wagner, on site for half the day, was anxious to leave. Although he was making overtime, it seemed the polling place duty isn’t a popular shift. “We get stuck with it,” he said.

It had been a long day for most of the workers, who like Wagner had to arrive at the polling site by 5 a.m. But unlike Wagner they didn’t get relived midday.

And because they get paid the same wage, no matter how long they work, many of the workers became more anxious to get done as the day dragged on.

“You have to wait when someone else messes up,” said Dixon. “I’ve been here where you have to stay here until 3 o’clock in the morning.”

As it got closer to the close of the polling at 9 p.m. the site coordinator, Helene Jones, became more frantic. “Someone keeps taking my pens,” she said, scurrying from one table to the next.

Though she said she had fixed the ballot problems earlier, this didn’t stop her from shouting last minute directions from one side of the gym to the other, where some couldn’t hear her or were not paying attention.

But the sense of humor in the room was also starting to return, even as each table became serious about packing up their stickers and ballots.

“You have to have some laughs to get through these 16 hours,” said Furgusion.

“We’re the funniest table,” said Cooke.

“A lot of the other tables are very uptight,” said Dixon.

Late arrivals

At 8:54 p.m., seven minutes before the polls closed, as workers started putting away their materials, mailman Louis Afanador, 58, showed up after a long shift in Queens.

“Hurry up, Louis,” said Fergusion. “You’ve got five minutes.”

A few minutes later Duane Jones, 54, walked in straight from the 2 train but was turned away. It was exactly 9 p.m.

Jones had stayed late at his job at a printing press that night, despite being given permission by his union to use two hours of paid work time to vote, because his coworker was in the hospital.

“Our company is not doing as good as we used to,” said Jones, as he walked back home from the polling place. “I’m getting ready to buy a house. I don’t want to be looking for a job.”