Photo by: NYC.gov

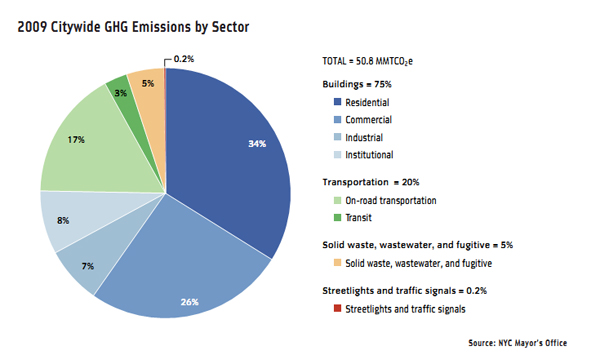

A graph from Mayor Bloomberg’s PlaNYC illustrates how crucial residential buildings are to any hopes for a greener city: Homes contribute twice as much carbon as cars and trucks in New York.

At the bottom of a hill on 168th Street is the old Morrisania Hospital, an elegant yellow-brick structure surrounded by apartment blocks in the South Bronx. The city abandoned the building during the fiscal crisis of the mid-1970s, and for 20 years the once-grand hospital sat empty and windowless, its interior a ruin open to the elements.

Nancy Biberman, president of the Women’s Housing and Economic Development Corporation, recognized the building’s potential, and a gut rehab produced 132 apartments for low-income and formerly homeless families, with health- and child-care centers, plus a commercial kitchen for small start-up businesses. The 1997 project won accolades, but soon WHEDco faced an unanticipated crisis.

“This building was going to tank the organization,” recalls Biberman, who says tenants routinely opened their windows in the winter to cool down overheated rooms. “We literally saw money blowing out the windows, and it was bleeding us.” Raising rents was out of the question. “But it would be irresponsible to continue to let things go. We would have gone bankrupt.”

The solution was an energy-efficient retrofit of the building, now known as Urban Horizons. But once WHEDco began to realize savings on such measures as low-flow water fixtures, energy-efficient appliances, and compact-fluorescent lightbulbs—and tenants saw their electricity bills decline—the search for green solutions turned into a permanent, evolving process. The organization even hired a sustainability manager.

WHEDco’s experience with Urban Horizons may ultimately be a valuable example in a city with an old housing stock and little available land. It provides one roadmap for existing structures to comply with stricter laws, as the Bloomberg administration implements regulations to make multifamily buildings more energy efficient and to stop the use of the most polluting grades of heating oil. The new rules will reduce energy consumption and bring down costs over the long term, but they also could put a more immediate strain on affordable housing.

New rules for a greener city

The city aims to slash carbon emissions 30 percent by the year 2030, blaming air pollution for 3,000 annual deaths and twice that number of emergency-room visits for asthma. The only way to achieve this goal is by increasing the energy efficiency of buildings, because buildings account for three-quarters of carbon emissions.

About 85 percent of buildings were constructed before the availability of energy-efficient technology, according to the mayor’s Office of Long-term Planning and Sustainability, so the new laws address the process of retrofitting, or the installation of new equipment in older buildings.

Last year, large apartment buildings had to start reporting their annual use of energy and water, forming benchmarks for improvement. Next year they’ll have to pay for energy audits, which will survey buildings and recommend measures to bring down consumption. In July, buildings will begin to eliminate the use of the dirtiest heating oil.