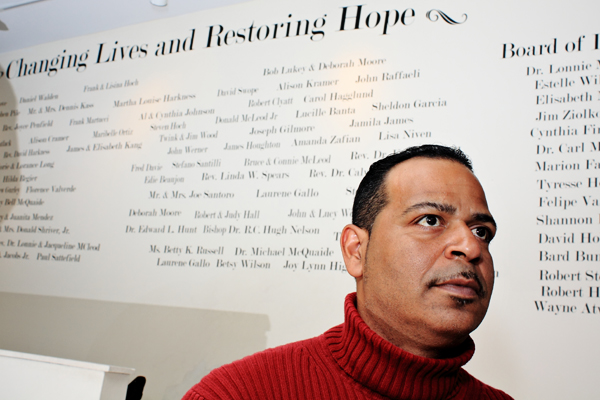

Photo by: Adi Talwar

A year after getting out of prison, John Molina was very active in the 2008 race. He knocked on doors, went to rallies, even got a bumper sticker. But one thing he didn’t do—couldn’t do—was vote.

In the run-up to the 2008 presidential election, 46-year-old John Molina—a self-described “political process junkie”—went all out. He attended rallies, put an Obama bumper sticker on his car and told all his neighbors to get out and vote.

“I’m one of those people that knocks on doors,”he says. “Don’t complain to me about your neighborhood, about the garbage in your street, if you don’t vote.”

But when November 4 came around, Molina didn’t go to the polls. He wasn’t allowed to. He was still on parole.

In New York State, anyone convicted of a felony and sentenced to time behind bars loses their right to vote while they’re incarcerated, and for the duration of their parole. For years, civil and prisoner advocacy groups have fought to restore this right, on the argument that ex-offenders who are civically engaged are less likely to fall back into crime, and make for better citizens.

“I was disappointed. Of course I was elated that Obama won, but I was disappointed I couldn’t be a part of the process,”Molina says.

He got out of prison in 2007, after serving eight years behind bars for armed robbery. After release, he worked hard to “reinvent”himself, he says. He got a job working for a nonprofit, went back to school for his bachelor’s degree and started taking classes for a master’s degree in public health at New York University. All the while, for the four years he was on parole, he couldn’t cast a ballot.

“People are still not allowed to vote even though they’re living the in the community, contributing to the community, sending their kids to local schools,”says Erika Wood, an associate professor at New York Law School.

Because a majority of those involved in the criminal justice system are people of color, advocates say the state’s felony disenfranchisement law stifles the voice of minority communities in the political arena, and is reminiscent of voting laws during the Jim Crow era. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, nearly 80 percent of the approximately 100,000 people who have lost their right to vote under New York’s law are African-American or Hispanic.

And while the majority of those behind bars can’t actively participate in the political process, prisoners still carry serious political clout—even if they can’t wield it. The state’s prison population is the rope in a longtime tug-of-war between upstate and downstate lawmakers over where prisoners should be counted as residents in the re-drawing of legislative maps.

Because these maps are based on Census population numbers, the districts set by the legislature this year will stay in place for the next decade. Last month, state lawmakers struck a deal, in accordance with a state law passed in 2010, agreeing—for the first time—to count prisoners as residents of their home addresses for the purpose of redistricting, as opposed to counting them in the districts where they’re incarcerated, as had been the practice for decades.

Civil rights and good-government groups have heralded the recent change as a landmark democratic boost to many New York City neighborhoods.

“The prison population is primarily made up of people of color, from low-income communities that have a lot of economic and social needs,”says Steve Carbó, of the advocacy group Demos.

“If their voice is being limited by parts of their community not being included, they have that much less political strength to get those needs meet.”

But while prisoners will be counted as residents closer to home under the new deal, neither they —nor parolees—will count as voters.

The chilling effect

Different states have different rules when it comes to letting ex-offenders vote. Some states, like Florida and Kentucky, permanently ban anyone with a felony conviction from voting, no matter how much time has passed since their offense, unless the government individually approves their rights be restored. Other states, like Maine and Vermont, let all prisoners vote, via an absentee ballot, even while they’re still behind bars.

“New York’s law is kind of in the middle,”says Wood.

Here, the law is different for different groups of offenders. Anyone with a felony conviction, whether on the local or federal level, who is sentenced to incarceration is barred from voting, for both their time behind bars and the duration of their parole. Those with a felony conviction who get probation instead of jail time, however, can still vote; so can anyone convicted of a misdemeanor, even if they’re incarcerated.

Right before the 2008 election, the Department of Corrections and staff at Rikers Island recruited advocacy groups to launch a voter education campaign at the jail, where a majority of inmates are there on misdemeanor convictions or are still awaiting trial, and therefore still eligible to vote.

Wood and others say that the complexity of the New York’s law creates confusion among formerly incarcerated residents and election workers alike, who might not understand the difference between probation and parole, or who think a misdemeanor charge can block them from the polls. That lack of clarity can keep some people from even trying to register, or to the state wrongly turning away someone who is, in fact, eligible.

“Our law here in New York State is sort of nuanced, and it’s exactly that nuance that creates a chilling effect, if you will,”says Glenn Martin, Vice President of the Fortune Society, a nonprofit that helps people coming out of prison and jail re-enter society.

“Misinformation is huge,”he says. “The law itself disenfranchises any number of people, but I would argue that the chilling effect disenfranchises many, many more.”

Martin, who himself spent time behind bars, says he was wrongly told by his local Board of Elections that he couldn’t register the first time he tried. A 2006 survey by the Brennan Center found that 24 of New York’s 63 local election boards either answered incorrectly or did not know if an individual on probation was eligible to register to vote; a 2005 survey of residents with current or previous criminal justice involvement, by the Sentencing Project, found that nearly 30 percent of New York respondents thought that an arrest in their past was enough to keep them from ever voting again, or said they didn’t know if that meant they were eligible.

Last year, the State Legislature passed a law that many hope will correct this trend, requiring criminal justice agencies to specifically notify those with a felony conviction of their voting rights as soon as they’re eligible to vote again.

Some advocates, however, say this isn’t enough, and that the only surefire solution is to restore voting rights to ex-offenders across the board, and as soon as they’re released from prison, even if they’re on parole.

“It eliminates some of those regulatory hurdles,”Wood says. Some version of a bill seeking that change has been introduced in Albany for years, but none have been passed.

Officially a citizen

Diana Ortiz spent much of her voting-age life behind bars. Sentenced to prison at 18, she was incarcerated for 22-and-a-half years, and then on parole for another three. She voted for the first time two years ago.

“I felt like: I’m officially a citizen. My vote counts,”Ortiz recalls. “It was one of the last acts of being an adult and being responsible. I felt empowered, like I was part of a community.”

Ortiz now works for Exodus Transitional Community, a Harlem-based nonprofit that works with people coming out of prison and jail. She and others in the field of re-entry say the case for restoring voting rights to those on parole can be made by looking at it as an important step to transitioning ex-offenders back into society.

“I would make voting a part of any prison release program,”says Gabriel Torres-Rivera, director of re-entry services at the Community Service Society. “You can ease their transition back by giving them this right; you can open them up.”

Civically engaged residents are more likely to be law-abiding ones, studies show. A report released earlier this year by the Florida Parole Commission found that ex-offenders who had their voting rights restored were less likely to end up back in the criminal justice system.

“What better way to have a person engage in re-offending than having them ostracized?”Martin says.

“Psychologically, it makes you not want to commit another crime,”says Julio Medina, founder at Exodus Transitional Community. “It makes you say, ‘Wait a minute, I’m here, I’m part of this community and I want to make sure the best things happen in this community.’”

‘It matters where we count people’

There are approximately 58,000 people incarcerated in New York’s prisons, and about half of those residents come from the New York metropolitan area. Of those, the majority come from just a handful of neighborhoods, like the South Bronx, Harlem and East New York.

For decades, inmates upstate were considered “constituents”of the districts where they were incarcerated—a process known by critics as “prisoner-based gerrymandering.”

Legislative districts are supposed to contain approximately the same number of residents, so that each district, hypothetically, holds the same political weight. Every 10 years, with the release of new Census data, a task force of lawmakers from both parties redraws the maps to adjust for population changes and to make sure the numbers are still evenly distributed across districts.

Critics of the practice of counting prisoners where they are incarcerated say it unlawfully shifts power to these upstate New York areas, meanwhile diluting the power of the low-income, minority communities downstate from which the majority of prisoners come.

“It matters where we count people,”says Peter Wagner, of the Prison Policy Initiative. “The Census Bureau is disproportionately counting a group of people, disproportionately black and Latino, in the wrong place.”

The legislative districts containing the largest numbers of prisoners are rural, largely white and often sparsely-populated areas of upstate New York, represented by Republican lawmakers who critics say don’t accurately represent the needs of the prisoners they count as constituents, who come from left-leaning areas and tend to quickly return to their home communities upon release.

“There’s a clear distortion of our democracy when you have local districts that are being padded by these phantom residents, who can by no means be considered real residents,”Carbó says.

What effect the 2010 law requiring prisoners to be counted in their home neighborhoods will have on how the actual legislative maps get re-drawn is still up in the air, though both Carbó and Wagner say the number of people who will now be counted downstate as a result is not enough for the creation of another, presumably Democratic, New York City district. The shift will only add about 25,000 people to the city’s count, a far cry from the 306,000 constituents required to make up a State Senate district, Carbó says.

“It’s not enough individuals to make a drastic change around the whole state,”he says.

But the changes could have repercussions for several districts upstate that, without their prison populations, fall below the threshold. Those districts would likely be consolidated or significantly redrawn, threatening the Republicans’ already slight majority in the Senate.

The state task force charged with coming up with new district lines, known as LATFOR, has yet to release any new maps, though its Republican members said last week that they want to add an extra seat to the State Senate, an attempt to hold on to the party’s slim majority there. The Republicans conceded earlier this month to count prisoners in their home districts, as the 2010 law requires.

Last year, a group of Republican lawmakers filed a lawsuit looking to block the new redistricting law. Sen. Betty Little, one of the suit’s lead plaintiffs, has a northern New York district that spans six different counties and contains 13 prison facilities.

An Albany judge rejected the lawsuit last month, though advocates predict an appeal.

“The state is majority Democratic, and the only way to draw a senate that is majority Republican is to engage in some very creative line-drawing,”Wagner says. “Being able to use the prison population as padding is one tool of the gerrymandering toolbox, and I believe the Republicans are going to use all of the tools.”