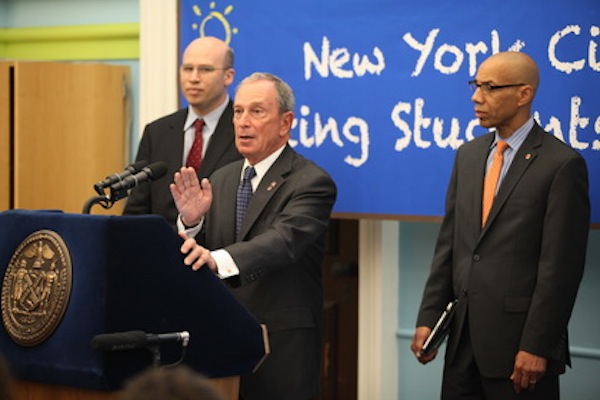

Photo by: Kristin Artz/City Hall

Chief Academic Officer Shael Polakow Suransky, Mayor Bloomberg and Chancellor Dennis Walcott discussing state test scores earlier this year.

On December 7, the National Center for Education Statistics released the results of standardized testing in 21 of the nation’s urban districts, called the Trial Urban District Assessment, or TUDA. As was true for most participating districts, New York City’s scores have largely stagnated since 2009, the last time the tests were offered. Changes in New York were so slight that none reached the level of statistical significance, according to the NCES. Yet New York City Department of Education leadership touted substantial gains.

“Scores for New York City students …have improved significantly” – since 2003, according to the Chancellor. In fact, scores rose by 6 to 8 points on three of the four tests in question – measures that assess reading and math proficiency in grades 4 and 8 – between 2003 and 2009, but not since. (The tests are graded on a 0 – 500 scale.)

NAEP the “gold standard”

National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, tests differ from state exams in that the test assesses student “samples,” rather than testing every student. Their results are expressed as averages because students do not receive individual test scores.

Walcott has called the NAEP the “gold standard” measure of student achievement. But NAEP differs in substantial ways from New York State tests, especially in its more-stringent intellectual demands, according to NYC DOE and New York State Education Department staffers – and the lack of harsh accountability consequences that accompany the test’s outcome.

School survival decisions are not tied to NAEP scores at the state or federal level, as is the case for state tests and for the No Child Left Behind criteria of Annual Yearly Progress, or AYP. Unlike the state tests, there’s no direct test prep for NAEP exams – children don’t practice taking the NAEP, and they don’t learn test-taking strategies or tips as part of their regular coursework or after-school programsFor NAEP advocates, this means that the test results are more objective, less vulnerable to coaching, and thus, more reliable.

NAEP scores don’t paint a rosy picture of American education – or of city students’ achievement. In New York City, about a third of fourth-graders are proficient in reading and math. For eighth grade, the news is worse: Just under a quarter of students score as proficient in the same subjects.

Better than Buffalo

Yet DOE frames these outcomes as gains, not cause for alarm: “The percentage of New York City students scoring at or above proficient has also climbed significantly since 2003,” in fourth-grade reading and math. Test scores have risen: Students from low-income families fare better in New York than elsewhere in the state and many parts of the U.S., for example –but rising to a level where most students are not proficient in reading and math is sour lemonade. City Journal‘s Sol Stern calls this the “We’re better than Buffalo” defense – DOE promotes its gains over other big cities in New York instead of acknowledging scant progress.

In fact, consistently fewer students are scoring at the highest levels, “above proficient,” on NAEP tests – a negative outcome that DOE omits from its official discussion of the city’s performance.

And since 2009 – the last time the exams were offered – progress is flat, scores stagnant. Some scores have even fallen backward: White and Hispanic fourth-graders’ math scores fell in 2011, even as scores for black students bumped up, by one point. (New York City’s hardly alone in this test-score plain: Scores for New York State and U.S. averages are all flat, essentially unchanged since 2009.)

At the state level, Education Commissioner John B. King was blunt: All lemons, and very little sugar. “The NAEP scores make clear a tough but necessary truth: Our students are not where they should be.”

King called the NAEP results “disappointing and unacceptable.”

“The goal is college and career readiness for every student, and that starts the first day a child walks into the classroom,” King said. In New York City, fewer than one in four 2010 high-school graduates were considered college-ready by New York State Regents’ standards.. (The State Education Department declined to respond to specific questions City Limits asked about New York City performance.)

Incremental progress

“On all four tests, low-income students outperform their peers across the nation, and that’s a reason to be proud,” said DOE’s Chief Academic Officer Shael Polakow Suransky. This is also true – but mixed news, in context: While New York students eligible for free- or reduced-price lunch outscored other low-income kids in urban centers and nationwide, NYC’s low-income fourth-graders score, on average, 18 points lower than better-off kids. This represents an improvement over the 24-point spread of 2003, but suggests a large distance still to be traversed. Low-income eighth graders in New York do better: their 34-point gap in 2003 has narrowed to 15 points.

These gains are real, but not as grand as Polakow Suransky’s praise might suggest: Poor children still score lower than middle-class children, and children of college-educated parents outscore classmates whose parents haven’t completed high school by nearly 20 points.

The persistent achievement gap that separates the races continues, only slightly narrowed: While it’s accurate to say that the gap that divides students of color from white and Asian students is smaller than in was in 2003, as DOE notes with pride, the decrease is slight: The reading score gap between African-American and Hispanic students and white and Asian fourth-graders, for example, closed by a single point – but still exceeds 25 points, overall.

In math, the average scores for white students in the public schools exceeded the scores of black and Hispanic students by a margin of 15 to 20 points, sometimes more. Notably, math scores dropped slightly for the city’s fourth-graders, by what NAEP describes as statistically insignificant margins. For English language learners, however, the 8-point drop since 2009 was statistically significant – but unremarked upon by DOE officials.

Overall, 39 percent of fourth graders were “below basic” in reading – more than were rated “proficient.” For children with learning disabilities and those learning English, twice as many were below basic – 73 and 74 percent, respectively, in 2011, compared with 70 percent for both groups in 2009.

Asked about these score changes, DOE spokesperson Matt Mittenthal told City Limits, “New York City students are in a far better place today than they were nine years ago, but we cannot be satisfied with current levels of performance.”

Between two tests

The city says that 44 percent of students in grades 3 through 8 are proficient in reading, and 58 percent are proficient in math.

NAEP’s proficiency scores are far lower, suggesting that between a quarter and a third of city schoolchildren are working at or above grade level.

Why the disconnect?

NAEP and state tests are different animals. They do not cover the same material (or “scope”) and they don’t demand the same sets of skills. New York state standards, which drive school survival, instruction and accountability, overlap with some NAEP standards – but significant gaps between what the state expects and what the national test measures undermine local students’ performance on the latter, according to DOE.

NYS Content Standards only support “a microcosm” of the objectives set forth in the NAEP framework, one DOE staffer said.

Differences in test design and rigor, including NAEP’s expectation that students will use math concepts and procedures to reason and solve mathematical problems, overshadow the “narrower set of skills” required by New York state content standards. That state standards have narrowed suggests that state goals, modified to assure steady progress toward NCLB AYP goals, have essentially undermined some of the higher-order thinking skills that NAEP assesses – and that, according to New York’s State Regents, are essential to college readiness.

For example, vocabulary is more demanding on NAEP; reading passages are longer and ask more of students. Half of the test items in the fourth-grade reading test require a ‘constructed response’ – otherwise known as original student writing. But for New York’s standardized assessment, 90 percent of questions are multiple choice, with many fewer challenges that ask students to synthesize, analyze and express their original thoughts.

“We are not satisfied with the level of progress since 2009,” DOE spokesperson Mittenthal said. Mittenthal added that higher academic standards, stronger curricula, and “turnaround” in the middle schools – Chancellor Walcott’s signature mandate – presages that “schools will naturally begin to adjust their instruction.”

Pending reforms at the state level will raise academic rigor, demand greater analytical skills, and lift student performance, the DOE staffer predicted.

How the city’s 1700+ schools, which will be integrating new Core Curriculum standards in 2012 and new state standardized tests in 2014, will evolve to “naturally” adapt to higher standards is an ongoing challenge, and one that will be inherited by the next administration.

Data from the NAEP: