January inaugurations are typically a time to look forward. Although it’s fashionable to spend the year railing against the shortcomings of politicians, new administrations give voters an opportunity to feel renewed and hopeful.

I, for one, am enjoying the moment. In New York City, new City Council stars, along with our new Council Speaker, Public Advocate and Mayor, promise a progressive era in New York City. But for me personally, it’s also a moment to consider what might have been.

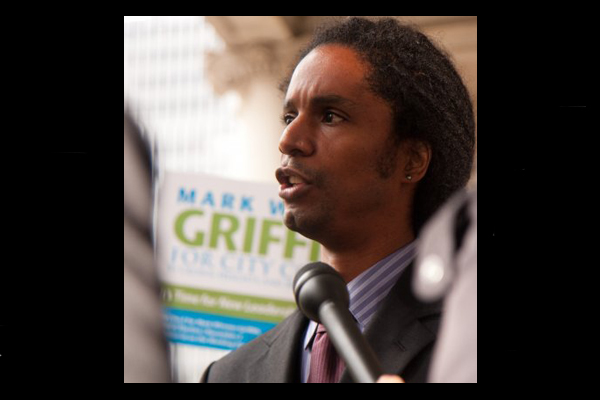

Four years ago I narrowly came in second to a forty-year incumbent in an eight-person race for the New York City Council. And two years ago, after establishing myself as the consensus front-runner in the 2013 contest, I ended my campaign for family reasons.

“Family reasons” is the cliché politicians typically use to avoid citing other, less noble, factors. In my case, family was indeed the sole reason. But to this day, some hardened political observers softly admonish me for my decision. In politics, the only thing that is truly respected, other than money, is winning. The fact that I did not show up to a race that I had a strong chance of winning was baffling and self-defeating in their eyes. For me, however, it was self-affirming and necessary.

Taking its toll

After the 2009 elections, I was praised and embraced by progressive colleagues throughout New York City for my strong showing and for helping to move the center of political gravity in Central Brooklyn. But the time I spent campaigning for the 2009 primary and general election, represented the most costly and personally invasive period of my life.

In order to have a shot of winning, I had to rearrange my relationship to everyone and everything that was important to me. I raided my Rolodex and converted every friend who had ever crossed my path since high school, and every family member, into a potential campaign contributor. I left the highest paying job I ever had and went the next seven months without a paycheck. I turned my home into a campaign office, and spent endless hours away from my wife and young children.

By the time the dust settled, I was in deep debt, unemployed and my marriage had suffered severe damage. This is often the price of the ticket for an insurgent candidate who is serious about winning.

There were longer-term professional repercussions too. In the wake of the 2009 race, along with some other neighborhood activists, I co-founded a community organizing group as an alternative way of building neighborhood power. But because my candidacy had threatened the political career and legacy of a powerful incumbent, I had became radioactive within local political establishment circles. Directors of peer organizations admitted that they were forbidden to work with me. At one point, I had to fight off a politically driven attempt to defund my organization.

These challenges only convinced me of my candidacy’s righteousness and the need to change the local political status quo. But, ultimately, my choice came down to either embarking on a promising political career and proving to the world that I could finish the electoral revolt I had started, or fighting to keep both my family and a promising social change organization in tact.

Crowded isolation

My campaign was a profoundly positive experience. I did so well because volunteers, my staff and I knocked on tens of thousands of doors. In doing so, I learned more about Central Brooklyn in one summer and felt more connected to my neighbors and our collective challenges than I had in years as an organizer. Holding intimate conversations with people of every conceivable demographic, in doorways, living rooms, backyards and stoops, was mind shifting. After I lost, instead of feeling broken, I was more inspired than ever.

But the campaign was equally isolating and not something I was anxious to relive. The best politicians embody ideas, represent the will of many, and walk with humility. At the same time, political campaigns and elected offices are almost by definition narcissistic pursuits. Unlike other public service enterprises, a single personality is ultimately the raison d’être and focus of the apparatus that surrounds them. As a result, people running for office become captives of, as the Working Families Party’s’ Bill Lipton likes to call it, their own “candidate bubble,” an often detached universe in which you can lose touch with outside reality.

Most local campaigns don’t have access to reliable polling data, and you can never verify which streams of advice you receive are of any value until the race is over. Candidates often confuse anecdotes and their own propaganda for the word on the “street.” If you don’t know what you’re doing, feedback delivered by random people you meet on the campaign trail can be mistaken for real data gathered from the tiny minority of people who actually cast ballots in your district.

As you hunt for dollars, institutional support and individual votes, the relationships you develop on the campaign trail grow increasingly transactional. And unless you are the clear favorite, potential allies who have their own political capital at stake will hedge their bets against you. You could be sure of someone’s support one day, and catch a picture of him cuddling up to your opponent on Facebook the next.

Wannabees

The moment my campaign ended, I joined the ranks of the also-rans. Like actors who are known forever for sit-com characters they’ve portrayed, most people who have lost a bid for local office never escape this dubious distinction—unless they win one day, of course. Whether they stand on the steps of City Hall, or merely show up at a PTA meeting, their simplest public action is perceived as a calculated positioning for the next electoral opportunity. People with a record of accomplishments are often reduced to political wannabees.

I hold deep respect for those who have remade themselves into newer, better public servants. Few people, for instance, remember or care that NY1 host and CNN contributor Errol Louis once ran for City Council in the nineties. Those of us who know him recognize that his political loss and his decision to not run four years later were the best things that could have happened to him and the rest of us.

I trust that I, too, cut a three-dimensional figure that transcends my one-time candidacy. But the truth is, when you repeatedly make, as I have, conscious decisions to keep swimming in the pond that is grassroots organizing, your professional options can be circumscribed accordingly. Today, after almost 30 years of this work, I strain to find positions that will honor my life experience and allow me to grow professionally, while paying me what I need—and deserve—to support my family.

The world of politics is a natural, sometimes inevitable, route for someone who has spent decades building institutions and fighting public battles on a neighborhood and city-wide level. It’s no wonder that you find veteran activists with no stomach for elected office, and an eye towards retirement, turning eventually to the financial security of government bureaucracies or foundations. Many just leave the game altogether.

After-life

I remain in the game. The organization I co-founded may prove to deliver more social change than I could as a councilman. But as I interacted this past political season with the candidates who would have been my competitors, and watched them survive the campaign gauntlet, I was sometimes overwhelmed by empathy and respect for what they endured. I can’t tell myself I would have beaten them because there is no such thing as “would have” or “could have” in politics. Those candidates had similar challenges as I did, perhaps even more, and overcame them. In the end, they had what it took to compete in 2013 and I didn’t.

Today my weeks are filled with daily school pick ups and drop offs of my sons, weekends given over to their soccer practices, bedtime story adventures, and vacations I get to enjoy with my extended family. What’s more, I’m part of an organization and social justice cause that is so much more than me.

I don’t know what my world would look like if I ran and won in 2013. All I do know is what I’ve chosen is not just a lifestyle worth leading. It may just be a life more whole.