Adi Talwar

A view of 535 Carlton Avenue (right of frame) and 550 Vanderbilt Avenue (left of frame) from Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. The developer wants to treat them as part of the same zoning lot in order to enjoy a bigger tax break.

Developers of 550 Vanderbilt, the first condominium building in the long-gestating Pacific Park (formerly Atlantic Yards) project, seem poised to turn a sweet deal into a bonanza, thanks to real-estate alchemy that super-sizes an already large tax break.

When Greenland Forest City Partners in 2015 prepared the Offering Plan for buyers at 550 Vanderbilt, the pending 421-a tax abatement meant an overall yearly tax bill of $1.2 million, a 69 percent discount off the annual property-tax hit that would have occurred without the tax break.

Now, however, owners at the 278-unit luxury building would collectively pay less than $123,000, a 97 percent discount.

But that $1.1 million increase in savings would be just the start. Since the new tax break would last 25 years, not 15 years like the initial one, plus remove an assessed value (AV) cap, owners could save a cumulative $86.5 million over the life of the tax benefit, by City Limits’ calculations. That would be $50 million more than in the earlier projection. (Neither the city nor the developer would address this estimate, which assumes static tax rates and assessments.)

How can they do this? By treating the luxury condo building and an affordable rental building down the block as a single “affordable project,” though several hundred feet and two future building sites separate the two. This allows the developer to avoid constraints that, under the version of 421-a in effect when construction started in 2015, applied to buildings in a broad zone of Brooklyn lacking affordable units.

The move delivers no new affordable units, because the apartments in 550’s partner building were already approved and subsidized, though it does prompt an uptick in affordability in 11 of those units. The administration of Mayor Bill de Blasio seems dismayed by the developer’s request but hamstrung by the fact that the change appears within the boundaries of the law that existed at the time shovels hit ground.

The 421-a application remains pending. The Department of Housing Preservation and Development responded to City Limits’ queries with a statement: “While approval will be based on whether all of the requirements have been met, this project underscores the reasons we fought so hard to reform 421-a to stop subsidizing luxury condos and incentivize the kind of rental housing our city badly needs.” (The new Affordable New York program requires 25 percent to 30 percent affordability in rental buildings, with various income mixes, limits the tax exemption to condo buildings with six to 35 units, and imposes an AV cap.)

Informed of the tax break and City Limits’ calculations, Michelle de la Uz, executive director of Fifth Avenue Committee, which has called for deeper affordability at the project, called it “ridiculous.” The developer, she said, “devised a way to substantially reduce their tax burden” while offering “extremely limited improvement in the affordability levels” in a project “whose ‘affordable housing’ is too expensive for most New Yorkers in need of housing… When will Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio say enough is enough?”

For the developer, though, it’s good news. “The joint application results in 10 additional years of exemption with no residential cap on the 421-a exemption and is a far better benefit than… in the original offering plan,” lawyer Paul Korngold wrote in a letter included among the changes to the Offering Plan, known as amendments.

Asked several questions related to this 421-a application and 550 Vanderbilt, the developer responded with a general statement: “Greenland and Forest City are proud to have completed nearly 800 affordable homes to date, working across business cycles and evolving policy regulations to meet our commitments. We continue to partner with the City and State to deliver on our shared vision for growing a vibrant mixed-income community at Pacific Park.”

Greenland Forest City (owned 70 percent by Greenland USA, an arm of Shanghai-based Greenland Holdings) surely faces pressure to sell apartments at or above listed prices, as its projected profit has seemingly shrunk.

In June 2015, Forest City Realty Trust (parent of Forest City New York, the original Atlantic Yards developer, and current 30 percent owner) estimated $361.6 million in overall building costs, with a projected sell-through of $388.6 million, suggesting an expected profit of $27 million.

This past August, however, it estimated $388 million in costs, with a projected sell-through—after minor price increases—of $391.1 million. That would seemingly leave a tiny $3.1 million profit, plus rental income from three retail units.

Lowered taxes reduce the cost of ownership without changing the sticker price—essentially a covert price cut. While Greenland Forest City told The Real Deal in July that two-thirds of the units had sold, more than half the building’s value—larger units representing more than $200 million—remained available.

The 421-a switch would especially boost the allure of the most expensive units, vaporizing taxes thanks to the removal of the cap. For example, the four-bedroom, 4.5-bath Penthouse West, priced at $6.86 million, was formerly projected to require annual taxes of $42,711 (already a 20 percent discount off taxes without 421-a). Now, annual taxes would be just $1,665. The buyer would save nearly $1 million more over 25 years, by City Limits’ calculations. Whether because of the anticipated bigger tax break or not, the joint venture recently raised prices slightly on five units.

Though no definitive database exists, the building’s overall $3.76 million annual savings seems unusually large for condos gaining a 25-year abatement. As of 2014, according to City Limits’ analysis of data compiled by the Municipal Art Society, the single largest annual saving in a 25-year condo abatement was $3.46 million. (Several condo and rental buildings in Manhattan, with either more units or valuable locations, had much larger annual abatements, but over a shorter time period.)

Ben Keel

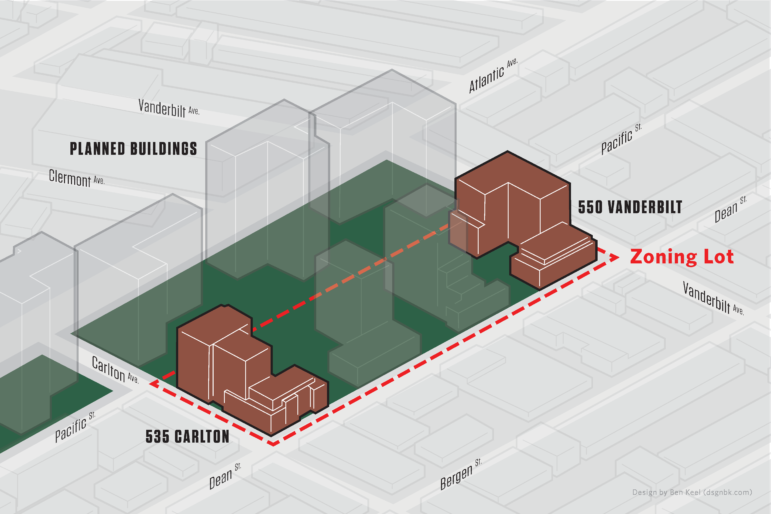

535 Carlton and 550 Vanderbilt are the only buildings constructed at the eastern end of the project site.

How can 550 Vanderbilt, long promoted as a market-rate building standing solo on Vanderbilt Avenue between Dean and Pacific streets in Prospect Heights, be part of what attorney Korngold stated would “be deemed to be an ‘affordable project’ by HPD”?

For the tax break, 550 Vanderbilt would be paired with 535 Carlton, a rental tower with 100 percent affordable housing at the far end of a long block, separated by two sites for yet-unbuilt Pacific Park towers. The pairing can qualify, according to Korngold’s letter, because both buildings were built at the same time and they share the same “zoning lot,” which the city defines as “a tract of land comprising a single tax lot or two or more adjacent tax lots within a block.”

The boundaries of that zoning lot were not publicly stated in the Atlantic Yards General Project Plan prepared by Empire State Development, the state economic development authority, which makes reference to multiple zoning lots. HPD says that the two buildings may be treated as one zoning lot because they are on the same block.

It is unclear—and neither the city nor the developer would say–how many affordable projects have taken advantage of such zoning-lot flexibility, though Ashley Cotton of Forest City New York said at an Oct. 17 public meeting that “we’re just applying like any other building under existing law, under the regulations that exist.” A project like Extell’s One Manhattan Square contains an affordable building adjacent to a market-rate building, without intervening building sites. After the rezoning in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, waterfront “development parcels” contained adjacent market-rate and affordable buildings.

Atlantic Yards, renamed Pacific Park in 2014, had already gained special treatment. Reform of the 421-a program in 2007, based on the widespread criticism that many subsidized buildings needed no tax incentives, expanded the zone in which onsite affordable housing was required in exchange for the tax break.

But the legislation offered Atlantic Yards–expected to contain 2,250 below-market units and 4,180 market-rate ones–what was widely called a “carve-out.” It allowed any exclusively market-rate buildings 421-a benefits as long as the project met an overall goal: 20 percent of the total units would be affordable to households averaging no more than 90 percent of Area Median Income (AMI).

That proposal was criticized by the administration of Mayor Mike Bloomberg, otherwise a strong supporter of the project, so it was pared back to 15 years from 25 years, reducing the estimated benefit by at least $100 million. Indeed, 550 Vanderbilt, according its 2015 Offering Plan, was slated to get a 15-year tax break.

After the passage of Affordable New York this year, however, Greenland Forest City recognized that the condo building could not get the 15-year tax break, Cotton said, apparently because the Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park “carve-out” wouldn’t be triggered until a cumulative 1,500 units were built. Instead, they pulled a rabbit out of a hat, concluding 550 Vanderbilt could take advantage of other 421-a provisions that few, if any, expected would be invoked for market-rate buildings in this project.

“Since this project commenced prior to January 1, 2016, it is covered by the 421-a law that was in effect at the time,” Korngold wrote, citing “require[ments] that 20 percent of the units in the application for 421-a benefits be made available for onsite affordable housing.”

Indeed, the 2007 legislation allowed “any multiple dwelling” within Atlantic Yards to gain the 25-year tax break, as long as it contained 20 percent affordable housing. Instead of having the tax break phase out over four years, starting in year 11, it would start in year 21. It also represents a vastly larger benefit, given the elimination of the AV cap, which as of 2017/18 set an $84,810 limit on the assessed value of an apartment seeking the tax exemption. Owners typically pay taxes on the value above the cap.

The increased tax break could be seen to raise the overall public cost for 535 Carlton because the city will now forgo more revenue in exchange for the same number of affordable apartments. Indeed, had the extended 421-a benefit surfaced before the July 2017 disclosure in an amendment to the Offering Plan, it could have put a damper on the city’s announcement a month earlier hailing the 535 Carlton opening, which Mayor de Blasio said was “delivering on the affordable housing this community was promised.”

The creation of a separate building with affordable housing in a sense recreates the “poor door,” a concept that Bruce Ratner, executive chairman of Forest City New York, has roundly decried, at least while highlighting plans for Pacific Park buildings with 50 percent affordable units.

Not only was the increased tax exemption not known when the 535 Carlton opened, there’s been no requirement to inform Brooklyn Community Board 8. HPD last year received confirmation that the an earlier 421-a application had been disclosed, as required, to the community board. But if the application is later amended—as happened in September—the sponsor is not required to resubmit it.

The “affordable project” has some curious aspects. Though 535 Carlton has been promoted as “100 percent affordable,” the 298-unit building contains mostly middle-income units too pricey to trigger the 421-a benefits for its zoning lot associate. It must supply 116 units, in various sizes, renting below 120 percent of AMI, to meet the required 20 percent affordability in the 576-unit pairing.

But the building has just 30 two-bedroom units and six three-bedroom units renting below 120 percent of AMI, while while 38 and nine are required, respectively. So eight two-bedrooms (previously said to rent at $2,611, or 130 percent of AMI) and three three-bedrooms (two at $3,009, 130 percent of AMI, and one at $3,716, 160 percent of AMI) must be reclassified at lower rents.

“[W]e had to make B14 [535 Carlton] more affordable, so the benefit on the affordability side is there,” Cotton said at the meeting. “But, in addition, another good benefit, depending on who you care about, is that B11 [550 Vanderbilt] has a 25-year abatement.” (Affordable housing advocate Barika Williams, who raised the issue at the Oct. 17 meeting, soon countered that “this vastly changes the amount of tax revenue these buildings will produce.”)

Cotton suggested that changes in 421-a had upended the developer’s plans for the Pacific Park, which is well behind schedule: “Getting a benefit for condos ever again is something we had counted on… and we no longer have that,” given that large condo buildings are excluded.

Even more strangely, after Greenland Forest City Partners in July announced a new real estate broker for 550 Vanderbilt, advertising for 550 Vanderbilt condos on the three web sites–550Vanderbilt.com, new broker Nest Seekers International, and the database StreetEasy–for weeks claimed owners would owe just $1 in monthly taxes, not the newly-shrunken figures disclosed in the developer’s documents.

When queried about this in July, the developer and broker didn’t respond. The $1 tax deal lasted for weeks on both Nest Seekers and StreetEasy, and still appears on 550Vanderbilt.com today, well after this reporter’s second round of inquiries.

6 thoughts on “With 421-a Maneuver, Pacific Park Developer Could Save Buyers $50 Million More in Taxes”

This whole 421-a thing is amazingly convoluted but your getting your ‘affordable’ units so what’s the problem? If you really want ‘affordable’ units where they are really needed then developers should be able to what Pacific Park did but across neighborhoods. Allow increased number of market-rate apartments in areas that can support such units in exchange for building affordable units in poorer neighborhoods where the land and construction costs are cheaper. Everybody wins.

But in this case, native new yorker, the affordable housing was already coming in. The developer is wrangling a deeper tax break despite adding no new affordable housing.

Problem is the developer does NOT lose money on the “affordable” housing units. Low income tenants pay so much and the Fed or State kicks in the difference between what the tenant pays and full market. So, some of YOUR tax dollars go to subsidize rents (not a problem) and the developer not only gets full market rent but a tax break on top of it.

Just like Real Property Tax Law 339y, 480a and others, 421a was crafted and passed by politicians as an end around the real property tax for wealthy property owners and developers. 339y forces assessors to value condominiums as an apartment building. New York state is a market value state meaning property taxes are based on market value as opposed to cost or income when valuing residential property. Condos are residential property but 339y forces the value to be based on income which produces a much lower value. If a luxury condo has a market of, say 200,000 then the income approach forces a value of about 90,000. The condo owner gets at least a 50% break on his home, unlike you or me. 480a is a forest land exemption providing owners of large tracts of woodland an 80% break from taxes. To get this the owner must have a plan in place to harvest, and sell, timber from the land. When was the last time you got an 80% tax break while making a profit? 421a in general means if “some” affordable housing is included in a development then the developer gets tax incentives. The developer may get favorable financing to build the project or get it paid with your tax dollars, rents the units based on income with the difference between the actual rent and market rent paid to the developer with, again, your tax dollars. Property tax wise the assessment must be based on what the tenant pays, not what the developer gets in total. As you can see this can be a huge screwing to taxpayers, just like the others mentioned. Is it time for the people to stand up and demand their politicians to put an end to these welfare exemptions for the wealthy? I think so.

Pingback: 2:00PM Water Cooler 11/8/2017 - Daily Economic Buzz

Please update. What is the status of the application now. Is there actually an abatement in place?