Jimmy McMillan’s performance in a gubernatorial debate in October 2010 sealed his status in New York political lore and cemented a six-word slogan into our vernacular. Today, he is fighting to hold on to his apartment from a nursing home in Queens.

Adi Talwar

September 30, 2022: James McMillan III, founder of the Rent Is Too Damn High political party. Mr. McMillan Is currently residing at a VA health facility in St. Albans, Queens.This story has been updated since original publication.

Exactly 12 years have passed since Jimmy McMillan, then-candidate for governor, sat on the debate stage at Hofstra University and seared a six-word slogan into our vernacular.

McMillan’s famous phrase went viral that night—earning him immediate Saturday Night Live treatment—and continues to live on in endless memes and timeless headlines by capturing a fundamental fact of life for millions of New Yorkers then and now: The Rent Is Too Damn High.

About two-thirds of New York City’s nearly 9 million residents rent their apartments and more than half of them spend at least 30 percent of their income on housing, an arrangement that means they are considered rent-burdened. The problem is only growing: Asking rents have risen faster here than any other large city in the country, according to a recent analysis of Zillow data by City Comptroller Brad Lander.

Median rents have spiked in every borough, reaching historic highs after a pandemic-induced plunge at the higher ends of the market. But low-income tenants saw no such COVID breaks. For them, the rent never stopped being too damn high.

So what does McMillan think about all of it?

“The rent really was too damn high,” McMillan, 75, said on a gray afternoon late last month. “And I knew it was going to get worse.”

City Limits caught up with the founder of the Rent Is Too Damn High Party at his current residence, the Veterans Administration nursing home in St. Albans, after a handful of conversations over FaceTime. McMillan, who served in the Vietnam War, has been staying there since February, when a stroke sent him to the hospital. He blames an improper dose of medication.

These days, he greets the occasional visitor inside the nursing home’s “Mets Pavilion,” an enclosed patio decorated with blue and orange metal chairs sponsored by the Queens ballclub. Quilts representing various branches of the military hang from the windowed walls, while a sign near the entrance advertises the 2013 Major League Baseball All Star game in Flushing.

McMillan’s familiar face and trademark white mane are thinner than they were during his two runs for governor, with multiple bids for mayor along the way. But he maintains the same elaborate mustache and continues to passionately denounce the plight of tenants, albeit in a quieter voice and with a smaller audience.

During the conversation, he recalled the debate performance that sealed his status as a legendary New York City political character.

“I put my gloves on in the backseat of the car at Hofstra University and I looked up at the heavens and I said, this is my moment. I took a comb and brushed my beard and said, ‘Let’s go to work,’” McMillan said. “My job was to try to use my entertaining ability to get people to pay attention.”

That they did, leading to a slew of articles and TV segments when McMillan found himself facing eviction in 2015. He decided to retire from politics soon after.

Improbably, he is still fighting to hold onto his apartment. The owners of his building at 107 St. Marks Place first moved to eject him from the then-$872/month unit in 2011, arguing that he kept another place in Flatbush as his primary residence and allowed his son to stay in the East Village apartment. McMillan countered that the Flatbush address was the headquarters of the Rent Is Too Damn High Party, not his home, and secured a stay of eviction in 2015 that allowed him to remain in the unit.

But McMillan then fell behind on rent a year later, court records show. He told City Limits that the owner, a limited liability company connected to developer Nader Ohebshalom, would not give him a key in an effort to drive him out of the unit. The landlord’s attorneys from the firm Borah Goldstein have not responded to emails and phone calls seeking comment.

In July, McMillan made a $10,737 arrears payment to the landlord after giving them another roughly $9,000 in March and April, according to court documents. His regulated rent is now just under $900 a month—not so damn high relative to most East Village apartments—and the court appointed the Jewish Association of Services for the Aged (JASA) as McMillan’s guardian during the previous eviction case. He has challenged that guardianship and said he now appears remotely to prove his capabilities.

JASA has not responded to emails seeking comment and McMillan said he has not applied for back rent through the state’s dwindling Emergency Rental Assistance Program, which has covered some arrears for tens of thousands of landlords while temporarily pausing eviction proceedings for applicants.

For many older adults, a nine-month nursing home stay often turns permanent, but McMIllan said he is committed to leaving the facility. His niece Tennille and close friend Erlene King, the current head of the Rent Is Too Damn High Party, agree that is possible so long as he continues to regain his strength. It will likely also depend on having an apartment to return to.

In the meantime, McMillan has been following the dramatic increases in the rental market. Though it takes McMillan some time to organize his thoughts and he meanders into conspiracy theories about stolen elections and the power of law firms to appoint judges, he speaks with ferocity when it comes to apartment costs.

“How can you be here if you can’t pay $5,000?” he said, referring to average rents in Manhattan. “The housing is limited.”

McMillan called for changes to current zoning laws that restrict the number of legal units on a property. He also slammed “Not in My Backyard” attitudes when it comes to housing homeless New Yorkers and recently-arrived immigrants making their way to the five boroughs. “All they need is a place to stay,” he said. “You’re sitting at a table for dinner, you have five plates. You have two people come and you’re gonna say, ‘No you can’t eat?’”

At that, he paused and began to tear up: “You change the housing laws,” he said.

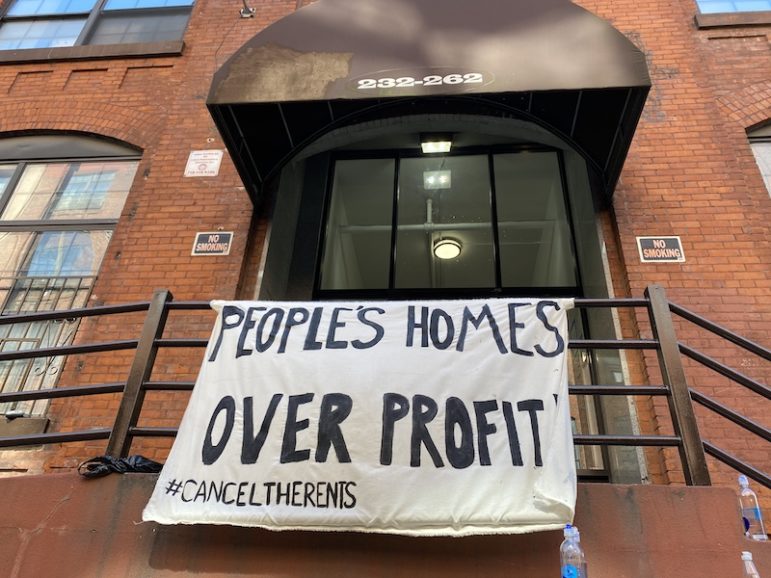

Sadef Ali Kully

A sign protesting rent collections in Brooklyn during the height of the Coronavirus epidemic.

‘We were never wrong’

McMillan’s performance on the debate stage more than a decade ago drew chuckles from the moderators and from another candidate on the stage that night, future governor Andrew Cuomo.

But McMillan isn’t fond of the ex-governor, or other Democratic party leaders in general. As far as he sees it, Democrats have failed to respond to rising rents and displacement, even though Albany lawmakers passed sweeping measures to extend rent regulation in 2019.

In 2016, he endorsed Donald Trump for president, saying the famous property owner—who was charged with discriminating against non-white tenants and whose company has been accused of lying about apartment improvements to illegally inflate rents—was the only candidate talking about veterans issues.

Now, he says, Democrats are too consumed with fighting Trumpism to tackle out-of-control housing costs. “You hear Donald Trump’s name. Donald Trump has nothing to do with this,” he said. “The Democratic party? [Tenants] have no one to fight for them.”

In 2005, McMillan made anti-Semitic statements blaming Jewish New Yorkers for high rents and later faced criticism for those statements following the 2010 debate. McMillan now says too many groups blame each other for the rising rents when they should work together. “It’s got nothing to do with that,” he said. “It’s about the Democratic Party wanting control.”

McMillan’s political ideology and controversies aside, his old friend King, who once challenged Jumaane Williams for his former Council seat, said she was hopeful the Rent Is Too Damn High Party would recapture the spotlight and motivate more young New Yorkers to vote.

King, now the formal head of the party, said she first met McMillan as he proselytized for lower rents aboard the B44 bus through Brooklyn. She helped him set up an actual political party, one eventually recognized by the city’s Board of Elections after a dispute over the word “damn” in the official name. BOE officials said the problem was the number of characters in the title, not the curse word, so McMillan changed the word “too” to “2” to meet the 15-character limit on ballots and official documents.

King said the quirky battle with the BOE underscored the purpose of the party in past election cycles: to raise awareness and generate attention.

“We didn’t run to win, we ran to get on the debate stage,” she said.

With rents soaring, King said the time is right for a revival.

“Next year, we’ll have our party active,” she said. “We were never wrong.”

3 thoughts on “The Rent Is Still Too Damn High: Catching Up With Jimmy McMillan”

It’s neither the Political parties or the Jewish people that the rents are too high. It’s the influx of the people coming from the Midwest states of Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin et al.

The Williamsburg crowd is the reason for inflating rents. Mayor Adams said it correctly a few years back when he said “go back to Ohio” or wherever you came from. These people are not the fabric of NYC. as long as this group of people keep moving to the city the rents will keep rising. We have to start changing an interstate moving tax from these states, and maybe they will stop coming to the city. They contribute nothing to NYC except for high rents and Trader Joes

Sick of rent being raised every year on subquality rentals masquerading as luxury apartments bc they stage a pool.

I had the pleasure of meeting this man when the memes were blowing up around Flatbush. His car was plastered with his face, and Rent is Too Damn High iconography.