The AAMUP plan could deliver 4,600 new apartments and other investments in Central Brooklyn. But passage by City Council may involve negotiations to increase the amount—and affordability—of housing at publicly owned sites.

Adi Talwar

A Department of City Planning public meeting on the Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan on April 16, 2023.The long-gestating Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan (AAMUP), which could deliver 4,600 new apartments, including 1,440 affordable units, plus job-creating space, street improvements, and city investments in Central Brooklyn, is moving forward, with a vote expected next month by the City Planning Commission.

However, passage by the City Council may involve negotiations to increase the amount—and affordability—of affordable housing at publicly owned sites.

In her testimony Feb. 5 to the Planning Commission, 35th District Councilmember Crystal Hudson said the 21-block AAMUP “has the potential to transform Atlantic Avenue and the surrounding area, turning vacant lots, self-storage facilities and gas stations into a vibrant, mixed-use neighborhood with deeply affordable housing.”

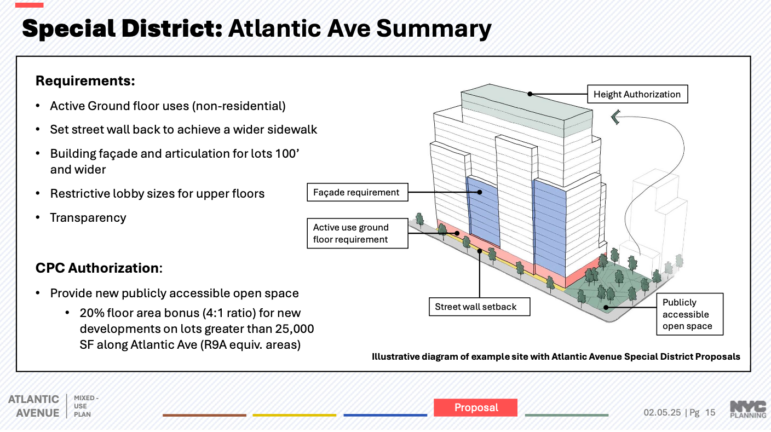

The rezoning boundaries stretch west from Vanderbilt Avenue to (nearly) Nostrand Avenue and as many as three blocks south and one block north. Buildings could rise 17 stories on Atlantic Avenue, 11 stories on some perpendicular avenues, and eight stories on inner blocks.

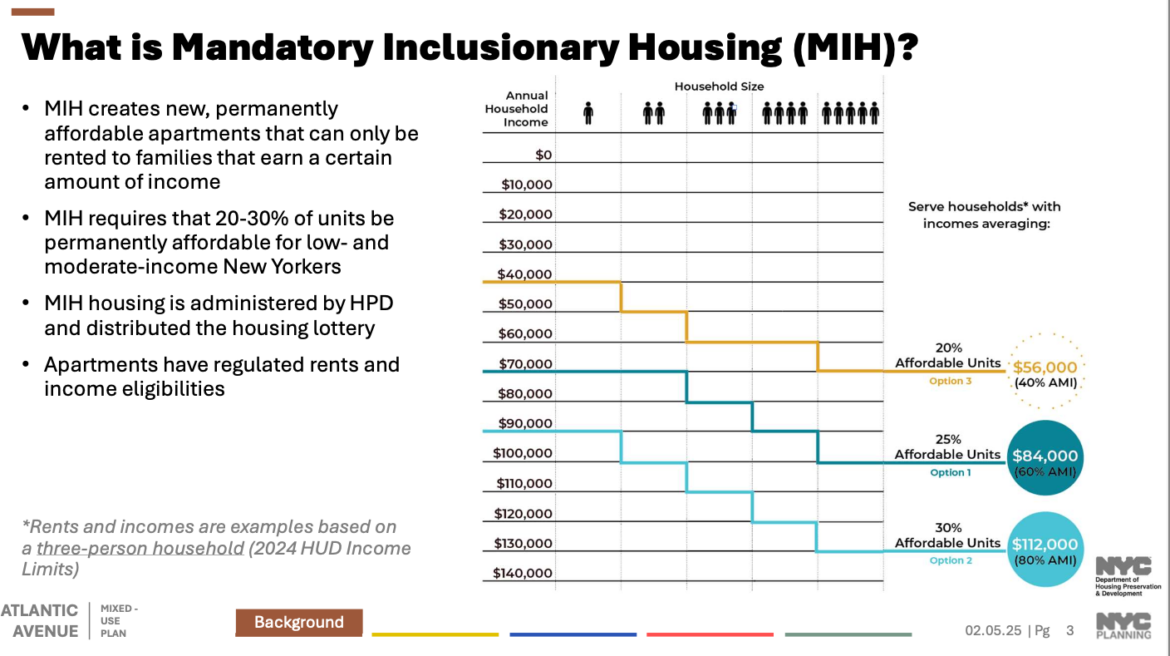

Under the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) rules, developments in rezoned areas need to set aside 20 to 30 percent of units as income-restricted. Despite her enthusiasm, Hudson said more is needed.

“The community has been clear that AAMUP must go beyond the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing [MIH] requirements, increasing the supply of deeply affordable housing, through both new construction and stronger preservation investments, and we can do that by leveraging every potential city-owned site in the area,” Hudson said.

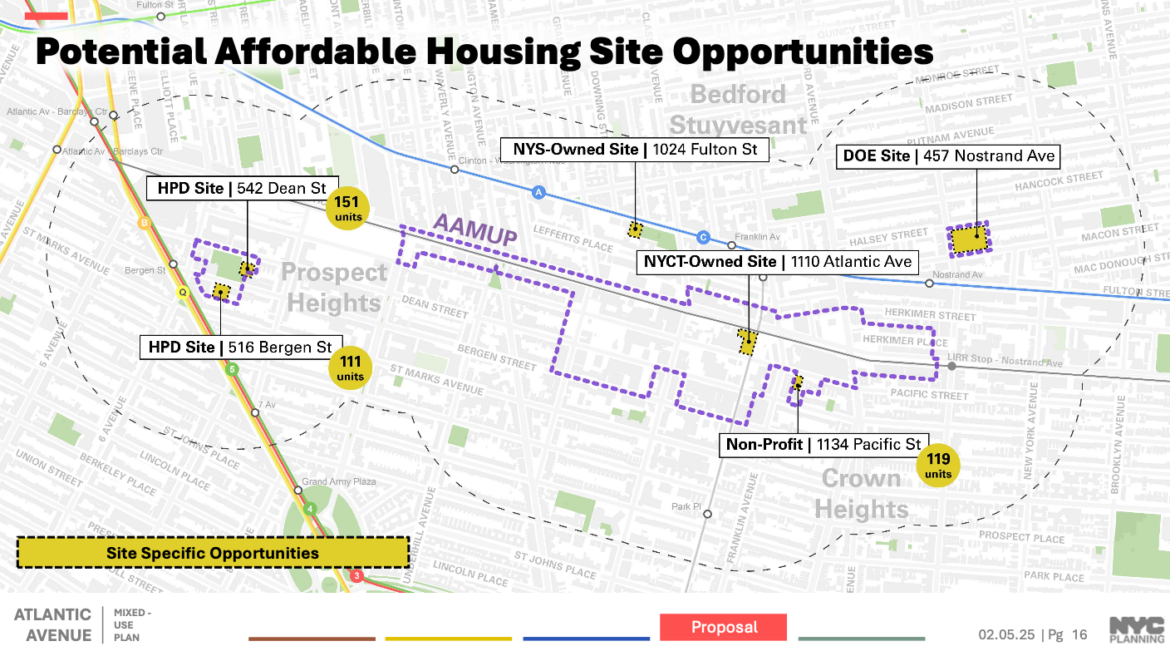

While the Department of City Planning (DCP) listed six standalone affordable housing sites in its presentation—five publicly owned and one owned by a nonprofit— Hudson added another. Only two of those seven sites are located within the rezoning boundaries; the rest are relatively nearby.

Dept. of City Planning

For now, DCP projects 1,055 MIH units at privately owned sites, plus 381 apartments in 100 percent affordable buildings. The latter total, however, encompasses just three sites, perhaps leaving room to announce a larger commitment when Hudson, along with 36th District Councilmember Chi Ossé, wrangle approval later at the Council.

A primary goal with the AAMUP plan is “to bring more affordable housing to my rapidly gentrifying district,” Hudson told City Limits in a statement, noting the district had lost “20 percent of our Black population in the decade preceding my term.”

Citing a Community Vision and Priorities report that stressed affordable housing, safer streets, small business support, and preservation of light manufacturing, Hudson said, “Though we are still negotiating with the Administration, I am confident that the final agreement will secure many of the community’s priorities.”

Limiting MIH options?

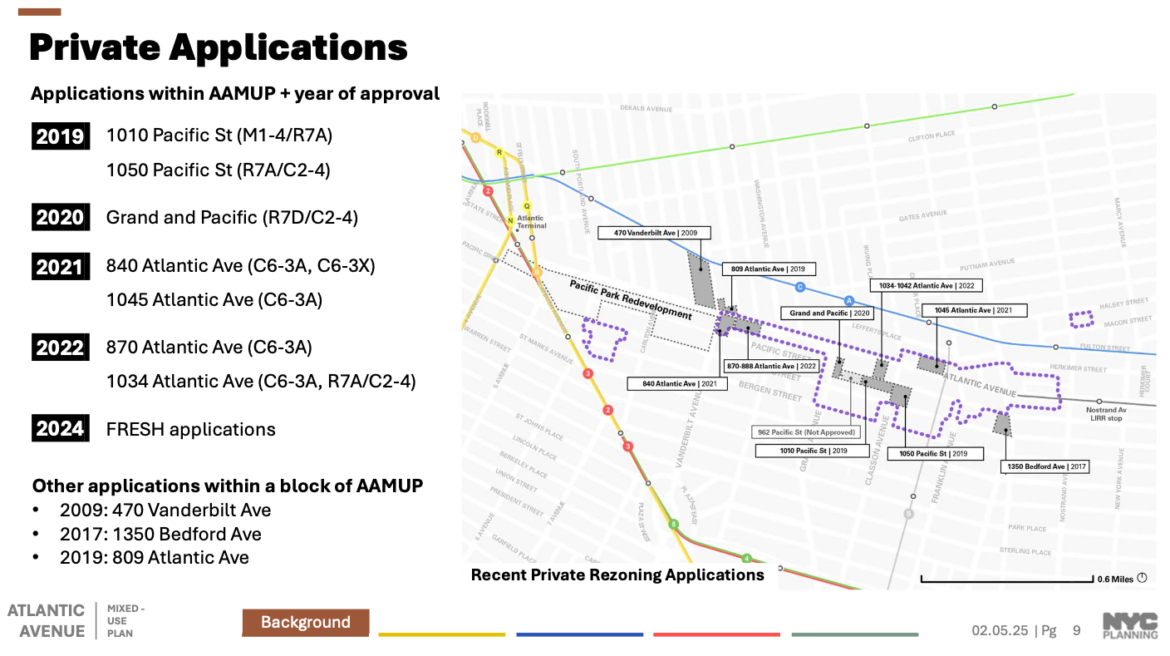

Speculation on blocks long shackled by outdated manufacturing zoning was spurred by the slowly-gestating Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park plan at the rezoning’s western border and gentrification, combined with development constraints in nearby blocks controlled by contextual zoning or historic districts. So Brooklyn Community Board 8 pursued a rezoning proposal, known as M-CROWN (Manufacturing, Commercial, Residential Opportunity for a Working Neighborhood), a precursor to the current plan.

Since 2019, seven private rezonings have been approved in the area, six of them within CB 8 and one in CB 3. In 2022, Hudson notably negotiated 35 percent affordability at two Atlantic Avenue parcels, more than the maximum 30 percent under the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing, and at lower average rents: 54 percent of Area Median Income (AMI).

Dept. of City Planning

CB 8 conditioned its support for the Atlantic Avenue plan on the city removing the two main MIH options for developers, leaving Option 3, the Deep Affordability Option, in which 20 percent of units must be affordable to households earning 40 percent of AMI, or $55,920 a year (as of 2024) for a three-person household.

Along with Option 3, DCP seeks to map Option 1, which requires that 25 percent of the housing be affordable to households earning 60 percent of AMI, or around $83,880 a year for three people. DCP also proposes Option 2, with 30 percent of the units aimed at households earning 80 percent of AMI, or around $111,840 a year for three. Most developers would choose that more lucrative option, AAMUP steering committee member Gib Veconi, who led the M-CROWN efforts, told City Limits in September 2023.

Dept. of Housing, Preservation and Development

Can MIH be revised?

CB 8, frustrated with a pattern of local displacement even as the area’s housing supply has increased ahead of the city average, proposed a new MIH option 3.5, mapped with 40 percent of floor area targeting an average of 30 percent of AMI, or $41,940 for three people.

Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso, in his conditional approval, recommended that DCP analyze that proposal, noting that MIH is based on a market and financial study from 2015. “Given the significant changes in market conditions since then,” he wrote, “DCP should update this study to ensure the MIH program reflects current realities and needs.”

At the City Planning Commission hearing, Commissioner Juan Camilo Osorio, a Pratt Institute urban planning academic, asked about CB 8’s proposal. Such modifications would be out of scope, he was told by the Department of Housing Preservation and Development’s (HPD) Aleena Farishta. She noted that, thanks to the City of Yes changes passed last year, the Deep Affordability Option was enabled as a standalone option for the Council to choose.

Osorio suggested that the “specific conditions of this community” meant the proposal deserved consideration. Alex Sommer, director of DCP’s Brooklyn office, cautioned, “I don’t think we yet have the tools or capability to modulate based on very micro, local neighborhood financial considerations.” He acknowledged that they’d “heard loud and clear from the community board about deep affordability,” and could pursue that on public sites.

“We understand an amendment to MIH was not intended to be part of the AAMUP rezoning,” Sharon Wedderburn, chair of CB 8’s Housing and Land Use Committee, told City Limits after the hearing. “However, if the city intends to continue to add housing units through neighborhood rezonings in districts that have seen significant increases in median rent in combination with demographic changes that indicate substantial displacement of residents, we expect it will continue to hear demands to go further with affordable housing.”

Hudson told City Limits that the Council should bring stakeholders together to update MIH and “provide deeper affordability specifically in rapidly gentrifying communities.” She didn’t comment on whether she backed Option 3 as a standalone.

MIH negotiations

There can be room to go beyond MIH. After the City Planning Commission hearing, Councilmember Shahana Hanif negotiated 40 percent affordability, at 60 percent AMI, in a spot rezoning in Windsor Terrace, pointing to the economic feasibility of such deals in certain neighborhoods.

Hudson in February 2024 voted down another spot rezoning, at 962 Pacific St., suggesting it was presumptuous to say the proposal was consistent with the “comprehensive planning for this area.” CB 8 had gotten the developer to promise 32 percent affordable housing—more than MIH—after the developer offered 25 percent, consistent with MIH Option 1.

“The whole purpose of doing the rezoning was not to continue approving projects one by one without the full context of the area,” Hudson later said.

Under MIH, whoever builds at 962 Pacific would seemingly have a lesser affordable housing obligation than negotiated, but would no longer have a head start on competition. Hudson didn’t respond to a query about comparing the previous promise with the likely scenario.

New support for tenants?

At the Planning Commission hearing, Osorio also asked about CB 8’s proposal that HPD establish a registry for tenants displaced from the AAMUP study area, giving them preference for half the affordable apartments developed as part of the rezoning plan.

HPD Neighborhood Planner Paula Diaz noted that the city’s longstanding 50 percent community preference in affordable housing lotteries had already been challenged as violating fair housing law. Under a settlement announced in January 2024, the local preference was cut to 20 percent and will, after five years, reach 15 percent. “So we have the same limitations there,” she said.

She noted that, thanks to the City of Yes passage, $7.6 million was restored to the city’s Anti-Harassment Tenant Protection program, and the agency was exploring the possibility of local expansion. CB 8, however, seeks $3 million a year, over five years, to both defend against evictions and to stave off other displacement tactics.

As CB 8 and Crown Heights Tenant Union member Sarah Lazur commented at the borough president’s hearing on this rezoning, more than half of tenants are unrepresented in housing court; meanwhile, when landlords try to deregulate apartments, tenants “are completely unrepresented” during proceedings of the state Division of Housing and Community Renewal.

Hudson, in her testimony, said, “We must secure dedicated funding for legal support for tenants facing eviction or experiencing landlord harassment.” She didn’t attach a dollar figure.

Atlantic Avenue changes

Hudson also seeks “a fully funded commitment for a comprehensive redesign” of dangerous, broad Atlantic Avenue, given the expected new population. Reynoso went further, saying the Department of Transportation (DOT) must commit to a road diet from six to four lanes along Atlantic Avenue, in line with the rest of the corridor.

Adi Talwar

NYC Councilmembr Crystal Hudson speaking at a public hearing about the rezoning in 2023.At the hearing, DOT City Planner Dash Henley said a separate study would be needed to assess a road diet. Meanwhile, the agency plans safety improvements at various intersections in the area, including painted curb extensions and enhanced crossings.

Given the expected increase in population, Veconi, speaking as chair of the Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Council, urged that at least half of Atlantic Avenue “should prioritize people and nature,” offering “safe and healthy walking and biking environments.”

New open space possible?

In this auto-centric area, open space options are limited. After Osorio asked about such city commitments, Sommer pointed to a $24 million investment in St. Andrew’s Playground, which is outside the rezoning border, 2.5 blocks east of Nostrand Avenue.

Sommer acknowledged a trade-off, on public sites, between affordable housing and open space. “We are working to try and balance that: to maximize affordable housing on public sites and then reinvesting in existing open spaces,” he said.

The rezoning does propose a floor area bonus for developers supplying public plazas on large Atlantic Avenue lots: four additional square feet for every square foot of open space.

Dept. of City Planning

Industrial jobs

Echoing CB 8’s long-standing push for jobs within the rezoning, Hudson noted that, unlike with the special Gowanus Mixed-Use District, “AAMUP currently lacks the tools needed to ensure these outcomes.” She suggested modifying the incentives for job-creating space and requested funding for job training and business development.

Reynoso, in his recommendation, said the city’s efforts to incentivize manufacturing through zoning fall short, because residential space would always be more valuable. He said his support was contingent on DCP mandating manufacturing uses in part of the rezoned area.

Oversight

CB 8 also requested that the city fund a consultant to facilitate oversight, over 10 years, of the promised benefits. Wedderburn, in her testimony to the Planning Commission, said that reflected a lesson from the adjacent Atlantic Yards project, where 876 more required affordable units face a May 2025 deadline, which won’t be met.

While the Gowanus rezoning did create a similar stakeholder task force, it was funded through a private grant. To foster accountability, she told City Limits, it “should be funded by the city to level the playing field for any district where rezoning is proposed.”

To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.