Councilmember Crystal Hudson’s development framework details criteria that projects in her district should meet if they need city approval for zoning changes. “We can all contribute to the housing crisis that we’re in and build more housing, but do so in a way that’s really responsive to the needs of our local communities,” the lawmaker said.

John McCarten/NYC Council Media Unit

Councilmember Crystal Hudson, pictured during a tour of her district in 2022.Frustrated with the piecemeal approach to development in her district, a city councilmember introduced a comprehensive framework for developers that she hopes could guide projects across the city and set a precedent for her peers.

On a rainy Friday afternoon in mid-April, Councilmember Crystal Hudson convened a press conference at the Brooklyn Public Library to unveil her framework for projects that require a zoning change in Council District 35, which spans Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, Prospect Heights, Crown Heights and part of Bed-Stuy.

Designed to complement the traditional Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), it offers developers two tracks of criteria that residential projects should meet if they need city approval for increased density, height or other zoning changes.

“It’s really about engaging as many people as possible, and more people that aren’t traditionally included in the formal processes that we have to ensure true representation and that everybody’s voices are heard,” said Hudson, who sees potential for other councilmembers to adopt a similar framework for their districts. “So that we can all contribute to the housing crisis that we’re in and build more housing, but do so in a way that’s really responsive to the needs of our local communities.”

The framework is separate, according to Hudson, from the aim of the Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan (AAMUP), an ongoing city-led effort to rezone 13 predominantly industrial blocks near the thoroughfare to facilitate more development. Hudson and other lawmakers had pressed for that initiative, citing the need for a more comprehensive plan in the face of several spot upzonings proposed by developers in the area recently.

In February, the Council followed Hudson’s lead in voting against a 150-unit project planned for Pacific Street that sought approval for a zoning change, urging the applicant to wait until the wider AAMUP plan is in place. “The whole purpose of doing the rezoning was not to continue approving projects one by one without the full context of the area,” she told City Limits of that decision.

Adi Talwar

Hudson during a walking tour of the Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan (AAMUP) area in April 2023.Her new framework for the district as a whole makes a similar case. “Current land use decisions are made piecemeal,” it reads. “Many of these decisions don’t consider the surrounding area or incorporate resident input; instead, these isolated decisions can hurt communities and displace long-standing residents.”

To craft the framework criteria, Hudson’s office partnered with Hester Street, an urban planning nonprofit, to conduct a district-wide survey, garnering over 1,000 responses from community members.

The findings revealed a significant financial strain: more than three-quarters of respondents said they pay 30 percent or more of their monthly earnings on housing, irrespective of income level. Even among those earning above $100,000 a year (36 percent of respondents), affordable and supportive housing still emerged as their top choice for what their district needs more of.

The need for affordable grocery stores was another primary concern, as were commercial rent prices, which 44 percent of those surveyed said were the biggest challenge for small businesses in the area.

Using this input, Hudson’s office formulated a list of priorities for developers to include when pitching new projects. To gain Hudson’s approval, they need to fulfill one of two tracks: The first would prioritize deeply affordable housing and/or access to homeownership, while the second sets standards for mixed-income rentals.

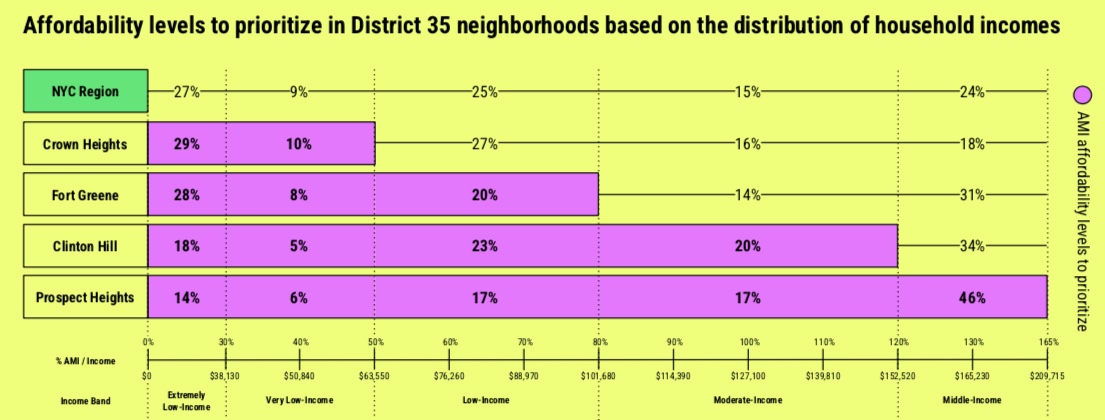

The councilmember won’t support rental projects unless they include some portion of income-restricted apartments. The first track under the framework calls for at least 80 percent of units to be affordable to households earning up to 80 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI)—about $111,840 for a family of three—portions of which must be set aside for earners in “extremely low income” and “very low income” bands. It also includes affordability requirements specific to supportive and senior housing projects, as well as a breakdown of household incomes in the district by neighborhood, as well as race and ethnicity.

Crystal Hudson’s Development Framework

The framework includes a breakdown of household incomes in district 35 by neighborhood.“So instead of relying on the area median income determined for the New York City region, the development framework includes the actual median income for District 35 neighborhoods and parses it further by race to identify which AMI brackets to prioritize in each neighborhood,” said Hudson.

The other option in the first track is for projects that include subsidized homeownership opportunities, such as those under the Department of Housing, Preservation and Development’s Open Door program. At least half those units would have to be available to households earning 80 percent AMI or lower, or alternatively, 75 percent be made available to households earning up to 100 percent AMI.

Under the second track, developers seeking to build mixed-income projects with market-rate units would have to “meaningfully” surpass the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) requirements—in which at least 20-30 percent of apartments in projects that benefit from an upzoning must be income-restricted.

Alongside those prerequisites, developers must meet a series of other baseline criteria: incorporating universal design principles for accessibility, proactive pest management practices, and a commitment to sustainability. Moreover, they must pay workers a living wage and prioritize the employment of local residents from disadvantaged and underrepresented backgrounds.

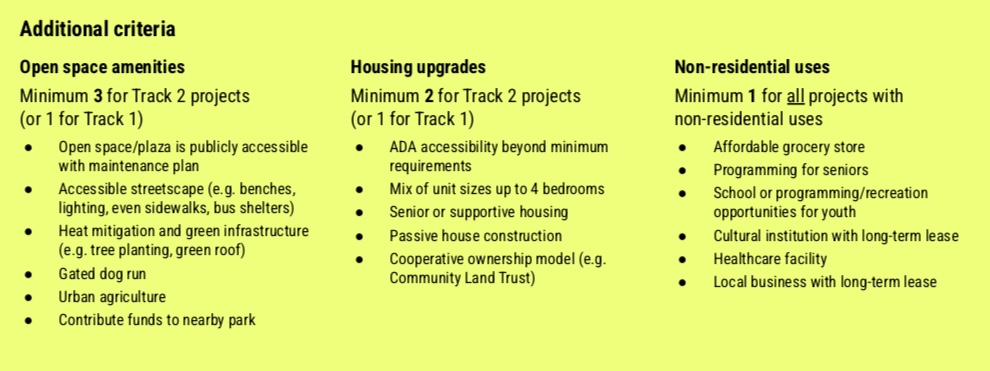

Projects in both tracks must fulfill additional criteria across three categories: providing open space amenities like a dog run or plaza area, “housing upgrades” such as senior and supportive apartments or the inclusion of four-bedroom units, and “nonresidential uses” like an affordable grocery store or health clinic.

Crystal Hudson’s Development Framework

Projects must include a certain number of other community benefits.

But District 35 is one of many parts of the city Hudson believes could benefit from the planning model, noting some of her colleagues are creating their own versions, like Councilmember Julie Won of District 26, which encompasses several neighborhoods in western Queens.

“Since taking office, I have advocated for comprehensive planning over piecemeal zonings parcel by parcel and created my own land-use principles to holistically address our community’s needs for affordable housing, schools, parks, transportation, sewage infrastructure, and climate resiliency,” said the councilmember in a statement to City Limits.

She noted that her district also has “vastly different” income levels and unique needs.

“Therefore, following CM Hudson’s land use planning process, I advocated to fund two separate comprehensive plans/neighborhood studies to gather targeted findings to inform decisions about how we use our land,” continued Won. Those studies include the “Heart of the District” (also with Hester Street), which focused on parts of Astoria, Woodside, and Sunnyside, and “One LIC” with the Department of City Planning (DCP) and WXY around Long Island City.

Gib Veconi, chair of the Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Council and longtime member of Brooklyn Community Board 8 in Hudson’s district, said he was impressed by the councilmember’s new framework. But he also questioned its long-term viability and the role of community boards “that may or may not see things the same as the city councilmember ordinance.”

“After there’s another election, what happens? What if the incoming city councilmember has a different view of things than the outgoing one?” he asked. “What happens to developers who’ve already tailored their plans around the existing plan that the existing city councilmember put in place?”

Despite these questions, Veconi thinks Hudson is being “proactive” by laying out her district’s objectives and priorities. “Developers will read this, and they will be responsive to it,” he said.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Chris@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.

6 thoughts on “Building in Brooklyn Council District 35? Here’s What the Rep—And Community Members—Want in New Development”

There are other places to build besides CD 35. Her ‘demands’ will only push developers out of her district.

Needlessly complicated. We need a ton more housing everywhere.

The only restrictions I care about imposing on developers is that there should be more units on a lot than there were before they broke ground. Build housing until landlords are competing for tenants, not tenants competing for units.

Glad to see CM Hudson taking leadership on this issue with a comprehensive plan for development. Other “progressive” CMs should take note and not allow spot rezoning without A LOT of public benefits attached.

This is a prime example of something well-intended that will actually only slow down housing construction by creating an overly complicated web of idealistic requirements. I can understand incentivizing the inclusion of affordable housing units or subsidized homeownership programs, but I was shaking my head in disbelief when I got to the part about mandating the inclusion of things like gated dog runs and green roofs in developers’ proposed housing plans. I know this councilperson means well, but they are getting in their own way with this unrealistic wish list.

Since professional urban planning firm was hired to develop this plan, I assume they did an economic analysis of the impact of all these requirements. Would love to see a cost benefit analysis from an honest broker.

80% affordability requirement will never pencil out without heavy (and customized) subsidies from the City, which we all know it can’t really afford. I see the intent of putting your dream agenda out – but this seems like such a waste of time and a spit in the face of the last 7-8 years of work with CB8.

MIH projects – or the baseline level of affordability in the original rezoning plan (25-30% of units) would work in combination of the new 485x. This would make new housing units pencil out with a ‘decent’ return, a little better than buying a long term treasury bill. This is realistic and would yield a lot of housing in a matter of a few years.

What she is proposing now will yield 0 units in any years. Developers are not a charity and it’s strange to think these projects can bankroll extensive public services she is unable to provide for her district.