In a recent settlement of a federal lawsuit, New York City will modify its approach to affordable housing lotteries by imposing substantial cuts to the percentage of units reserved for local residents.

Adi Talwar

A building in Brooklyn with affordable units distributed via the city’s lottery system.New York City will amend its long standing practice of giving preference to locals applying for affordable housing lotteries in their neighborhoods—the result of a years-long lawsuit that accused the practice of fueling residential segregation.

Traditionally, 50 percent of affordable units available through the city’s housing lotteries must be allocated to residents from the specific neighborhoods where the development is taking place.

However, following the approval of a settlement by Manhattan Federal Judge Laura Taylor Swain on Monday, this preference for local residents will undergo a significant reduction, decreasing to 20 percent in late April this year and dropping to 15 percent in the next five years.

The lawsuit was filed in 2015 by the Anti-Discrimination Center and attorney Craig Gurian on behalf of two Black women, Shauna Noel and Emmanuella Senat, who were unable to get housing when they entered city lotteries outside the community districts they lived in.

The plaintiffs alleged the community preference had a discriminatory effect, causing a disparate impact on the basis of race.

“Since the city as a whole is more racially and ethnically diverse than most individual community districts, a preference for community-district residents naturally favors a less diverse applicant pool,” Gurian said during a Zoom press conference earlier this week.

“For the first time, we are moving away from the idea of racial turf,” Gurian added. “Every neighborhood should belong to all of us regardless of where we come from and regardless of where we want to move.”

The settlement closes a chapter in a nearly decade-long legal debate about how best to ensure equitable opportunities for New Yorkers, and comes as the city grapples with a housing shortage and uneven distribution of affordable homes.

The city has long employed the community preference policy in its affordable housing lottery system with the original intent to safeguard low-income residents in gentrifying areas. Affordable housing developers have largely endorsed the policy, as the added community benefit made it easier to get approval from local community boards and residents, helping to push projects through the City Council.

Speaking to the press on the decision Tuesday, Mayor Eric Adams called the community preference policy, “a double edged sword.”

“As much as we think we live in an integrated city, we live in a hugely segregated city. And many people have prevented building in communities to keep people out. Many people have used other methods to keep people out,” the mayor said.

The NYC Law Department referred City Limits to an additional statement from Adams, in which the mayor called the remaining community preference allotment “a critical tool” for providing housing opportunities “for New Yorkers in every neighborhood.”

Harry DeRienzo, president emeritus and special advisor to Banana Kelley, a community organization based in the South Bronx, said he used to favor the policy in the past but suggested it had outgrown its usefulness in recent years.

“While such preferences might have made sense in the 1960s, the dynamics have changed with gentrification, making the notion outdated,” he said. “Nowadays, people, especially the younger generation, are moving into areas once avoided by others, challenging the rationale behind a community preference based on geography.”

Howard Slatkin, executive director at Citizens Housing and Planning Council, called community preference—originally employed as part of the Koch administration’s efforts to redevelop low-income communities that were abandoned during the city’s fiscal crisis—“a tool that was used to allay concerns about gentrification as the city rebuilt neighborhoods.”

“We went from a city where abandonment was the predominant theme to a city where gentrification was the predominant theme, and I think that heightened the appeal and demand for community preference,” he said.

In adherence to the settlement terms, the city, while not admitting fault, has committed to resisting any future legal attempts to revert to the 50 percent community preference level.

It also will provide $100,000 each to Noel and Senat as part of the resolution, and beginning March 1, add new text to its housing lottery application portal saying: “New York City is committed to the principle of inclusivity in all of its neighborhoods, including supporting New Yorkers to reside in neighborhoods of their choice, regardless of their neighborhood of origin and regardless of the neighborhood into which they want to move.”

City Planning Commissioner and tenants’ rights attorney Leah Goodridge told City Limits the settlement raises other questions around the effectiveness of the city’s affordable housing lotteries, which can often feature apartments at higher price points than local residents can afford.

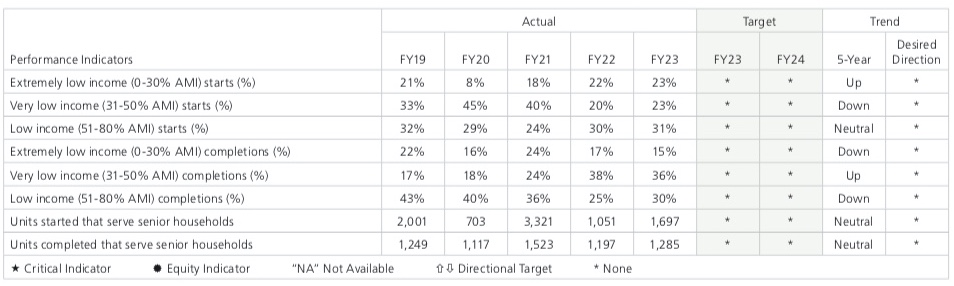

Of the affordable units created or preserved by the city during the most recent fiscal year that ended in June, 23 percent of started projects and 15 percent of completed projects were for households considered “very low income”—earning between 30 to 50 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI), or $38,130 to $63,550 for a a family of three.

Mayor’s Management Report/HPD

The city’s affordable housing production in Fiscal Year 2023, broken down by income level.A greater number of affordable units last year—31 percent of started projects, and 30 percent of completed ones—were earmarked for those earning between 51 to 80 percent AMI, or up to $101,680 for a three-person household, according to data published in the Mayor’s Management Report.

“A lot of the projects start at moderate income and don’t have as many units as they should for truly low income people,” Goodridge said. “When you look at projects that start at $80,000, for the affordable housing units in the Bronx, you have to wonder if the affordable housing itself is part of what is perpetuating gentrification.”

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Chris@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org.

3 thoughts on “Community Preferences Curtailed: City’s Affordable Housing Lotteries Face Changing Dynamics”

I would add that I also stated in the interview that even though geography based preference is now irrational, there is no reason why, after a century of discrimination of Blacks and other people of color through racial zoning, exclusionary zoning, Southern Jim Crow laws, Northern mob violence, redlining, FHA-required restrictive covenants, and plain old racism, there should not be a preference for those who bear the legacy of that racism.

It’s stupid to penalize people for just wanting to remain in their own neighborhoods, near friends. This will backfire because local councilmembers will be pressured to oppose ‘affordable’ apartment buildings if local residents are being excluded.

NEWSFLASH! Gentrification is still very much alive and well, displacing the poorer populations of many communities. Alleviating that problem was the purpose of these regulations – by giving residents at least a slim chance to remain in the communities where they had their roots— instead of being forced out by the rising rents that rampant development precipitates. Rather than reducing these ratios we should remove them from ALREADY wealthy neighborhoods, areas where there is no gentrification in the true sense of the word. Likewise, we need to limit the advantage to long-time residents of gentrifying neighborhoods. Of course NYC and America have long had a sad history of pushing out indigenous peoples, beginning with the original native inhabitants onwards. This with the mantra: “Hey, we like this place that you call home. It has potential. So get out!”