In New York City, accumulating wealth is many times more difficult for Latino and Black New Yorkers, according to a recent report by the Robin Hood Foundation.

Edwin J. Torres/ Mayoral Photography Office

The report found that nearly half of white New Yorkers own a home, while only 28 percent and 16 percent of Black and Latino New Yorkers do, respectively.Lea la versión en español aquí.

Everyone has heard the saying that wealth begets wealth, but the racial wealth gap also begets racial inequality.

In New York City, accumulating wealth is many times more difficult for Latino and Black New Yorkers, according to a recent report by the Robin Hood Foundation,* which analyzed data pulled from the group’s Poverty Tracker, a project in partnership with Columbia University that regularly surveys a “representative sample” of city residents.

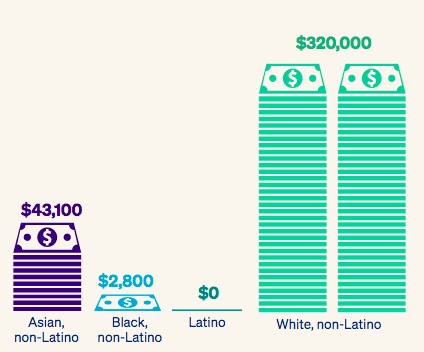

Unlike income alone, wealth is created in various ways and is calculated by adding all assets a person owns and then subtracting all debts. The report found that the median wealth held by Latino New Yorkers’ is $0, followed by Black New Yorkers at $2,800, Asian New Yorkers at $43,100, while the median wealth for white residents is $320,000.

Robin Hood

A graphic demonstrating the median total wealth of racial/ethnic groups in NYC.While wealth inequality exists in major cities across the country, wealth concentration is particularly severe in New York, experts explained, and closely linked to the high cost of housing. The report found that nearly half of white New Yorkers own a home, while only 28 percent and 16 percent of Black and Latino New Yorkers do, respectively.

The homeownership gap is even wider in other studies. For example, Urban Institute researchers estimate that Black New Yorkers hold only 12 percent of the city’s housing wealth, but represent 20 percent of the city’s population. Latino New Yorkers make up 26 percent of the population but hold only 11 percent of the housing wealth.

White New Yorkers, by contrast, hold 54 percent of housing wealth while representing 36 percent of the city’s population.

Andre M. Perry, senior fellow and director of the Center for Community Uplift at the Brookings Institution, said wealth is strongly influenced by historical factors that accumulate over generations. “History is kind of super vital for wealth,” explained Perry.

“Black people and brown people [are] climbing economic ladders in terms of income, because education is improving, people get experience, and you see greater opportunity lead to higher income,” he added. “But when you’re talking about wealth, you have to consider what has happened in the past, and we know that there were rules and laws that prohibited and/or throttled or restricted wealth.”

While income inequality has decreased nationally, experts explained, racial wealth inequality has not. “The gap has actually been growing for the last four decades,” said Madeline Brown, a senior policy associate at the Urban Institute.

Nationally, “in 1983, the average wealth of white families was about $320,000 higher than the average wealth of Black families and Hispanic families,” Brown explained via email. “By 2022, white families’ average wealth ($1.4 million) was more than $1 million higher than that of Black families ($211,596) and Hispanic families ($227,544).”

While Black and Latino families have generally increased their wealth over the past four decades, driven largely by home ownership, disparities have continued to grow because the vast majority of wealth in the country is held by white families, experts say.

“New York City is a standout in this regard, because it is hard living in New York City, and it’s harder if you don’t own property,” Perry added.

New York’s ‘rat race’

Bertha Chalar, an asylum seeker from Colombia, realized that between low wages and high rents in the city, it was very difficult to save money and there was no way to build wealth for her, her husband, and their two children.

“We fell into the rat race: living to work and not working to live,” Chalar, 31, said in Spanish. “Here, people have to sacrifice something: either to live huddled together or to eat badly.”

Chalar and her husband found work at an ice cream parlor and were able to leave the shelter system a few months after arriving in the city in 2021. But daycare for their youngest child was still too expensive. So for the past few months, she has been working on the long, complicated process of opening a new daycare of her own.

“The only way out is entrepreneurship,” Chalar said in a recent phone call with City Limits, as her son fussed in the background. “If we wait for a raise at work, it will not come. And if it does, it won’t be too much.”

According to Robin Hood’s report, only 7 percent of both Black and Latino New Yorkers have other assets such as a business, compared to 24 percent of white residents.

To start her own business, Chalar explains, she had to go through many other steps: obtaining an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number, opening a bank account, increasing her credit score, and completing a finance program with Ariva, an economic justice and financial inclusion organization based in the Bronx.

“This is the only way, and not to live on a day-to-day basis,” Chalar said. “I dream of having my own house and helping my mother in Colombia. It hurts me not to give. Now I am concentrating on my family.”

When it comes to homeownership in the city, historical racism fueled disparities and undervalued predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods. Black and Latino New Yorkers have faced discrimination in mortgage lending, while receiving higher denial rates and paying higher interest rates, experts explained.

“Redlining, racially restrictive deeds, and unfair mortgage lending practices have blocked non-white communities in America from one of the most reliable paths to wealth-building, owning a home,” said Richard Buery, Jr., CEO of the Robin Hood Foundation.

“Furthermore, densely populated minority neighborhoods were often a target of 20th-century urban renewal policies—such as the construction of interstate highways through neighborhoods like the South Bronx—that caused widespread displacement and property values to plummet,” Buery added.

Adi Talwar

A view of the Sheridan Expressway that cuts through the South Bronx.According to the report, the median value of home equity among white city homeowners is about twice that of Black homeowners, 1.5 times that of Latino homeowners, and 1.2 times that of Asian homeowners.

Assets from multiple sources

In addition, white households across the country accumulate wealth from a wider diversity of sources than Black and Latino households. According to the report, only 7 percent of the city’s Latinos and 8 percent of Black New Yorkers have achieved wealth of more than $500,000. In comparison, about 48 percent of white residents have this level of wealth.

“The gains in average wealth of white households have come from multiple sources including business assets and rental properties while Black and Hispanic households’ gains have come overwhelming[ly] from home equity,” said Joseph Dean, racial economic junior research specialist for the National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

New York City mirrors that trend. “Black and Latino New Yorkers are less likely to hold most asset types than Asian and white New Yorkers,” reads the Robin Hood report.

Again, the past and what you inherit is crucial, Perry insisted. “If you received an intergenerational wealth transfer, you simply have more resources to invest. And so we see those who are investing in the stock market in general have higher levels of wealth,” he said.

Anastasia Koutavas, a research analyst at the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at the Columbia School of Social Work and one of the report’s authors, explained that wealth levels also help protect against economic and financial instability.

“Assets can support your debts,” Koutavas said, “so assets not only help contribute to wealth levels, but also help prevent against economic and financial shocks.”

According to the report, slightly more than half (54 percent) of the city’s Latinos do not have at least $2,500 in easily available assets; 38 percent of Black New Yorkers are in the same situation, while this is the case for only 13 percent of white New Yorkers.

One factor to consider is what analysts call “wealth poverty”—when someone is unable to afford meeting basic needs for three months. Asian New Yorkers are roughly 1.5 times more likely to experience wealth poverty than white residents, Black New Yorkers are more than twice as likely, and Latino New Yorkers are more than three times as likely.

Last week, Mayor Eric Adams announced an additional $41 million for the city’s HomeFirst Down Payment Assistance Program, which provides up to $100,000 for down payments or closing costs to first-time homebuyers. He also expanded this assistance to moderate-income individuals and families earning up to 120 percent of the Area Median Income (up to $167,760 a year for a family of three).

The New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, which runs the program, did not provide City Limits with data on the race/ethnicity or incomes of people who have received this assistance since the program was created.

Expanding homeownership through this program was one of the Robin Hood report’s first recommendations for reducing the racial wealth gap in the city.

The report also lists proposals such as strengthening fair lending practices, “innovative ideas such as Community Land Trusts or a Public Bank that provides low-interest loans,” as well as robust Child Tax Credits and Earned Income Tax Credits.

*Robin Hood is among City Limits’ funders.

3 thoughts on “Tale of Two Cities: Report Finds Stark Racial Wealth Gap Among New Yorkers ”

Don’t worry. The whites and asians are being pushed out of NYC. So in a few years the progressives will have the crime-ridden dysfunctional minority-dominated city they have always wanted. LOL!

you should certainly leave ASAP. I think the rest of us progressive whites will be ok without you 🙂

Actually, the people that are being pushed out are mostly Black and Latino. This city is becoming more White and more affluent every year, while everyone else gets squeezed out of affordability. Which is the point of this article, and apparently your goal as well:

https://fiscalpolicy.org/new-census-data-show-population-growth-as-well-as-continuing-affordability-challenges