New York is the only state with a refundable child tax credit that excludes low-income families from accessing the maximum amount, limiting its anti-poverty effect, experts say. If the governor’s proposal is enacted, that would finally change.

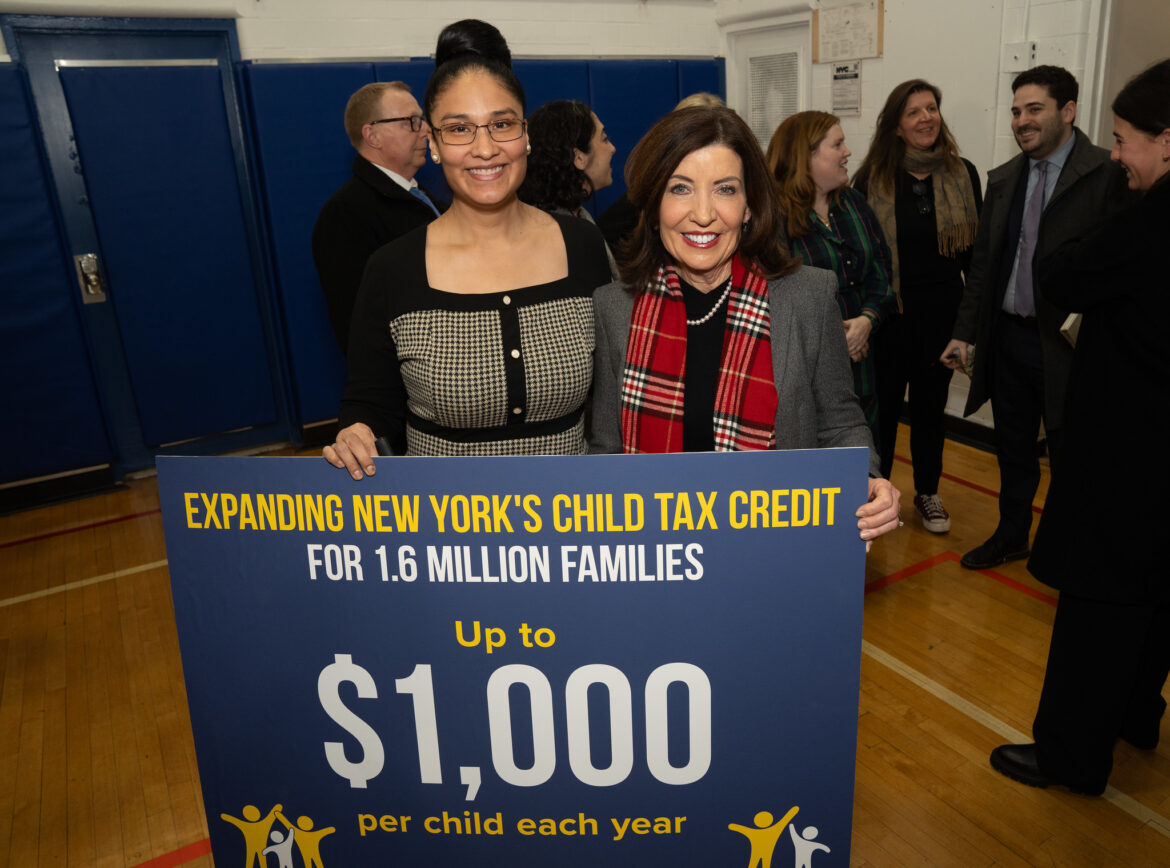

Don Pollard/Office of Governor Kathy Hochul

Gov. Hochul at a press conference earlier this month about her proposed child tax credit expansion.Lea la versión en español aquí.

Several priorities Gov. Kathy Hochul touted in her State of the State address last week—part of her vision for “putting money back in New Yorkers’ pockets”—aimed at reducing child poverty, and poverty in general; initiatives that advocates applauded.

Expanding the child tax credit is one proposal that researchers say could have a meaningful impact on New York State, where the child poverty level continues to exceed the national rate, as it has for more than a decade, according to data from the Schuyler Center For Analysis And Advocacy.

The governor’s proposal would expand the Empire State Child Credit (ESCC) to low- and moderate-income New Yorkers, increasing the maximum credit a household can receive from $330 to $1,000 for children under the age of 4.

The tax credit would be fully implemented over two years: in the first year, it would provide $1,000 to eligible filers with dependent children under 4, and in the second year, the credit would be expanded to provide $500 to filers with dependent children ages 4 to 16.

“The credit would begin to phase out when incomes rise above $110,000 for joint filers and $75,000 for single filers,” explained Ryan Vinh, a research analyst at the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University. “The credit would phase out at a rate of 1.65 percent for each dollar above these income thresholds.”

Currently, families with an eligible child whose members have different immigration statuses, and who file their federal taxes using an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN), are eligible for the ESCC. Hocul’s proposal doesn’t plan to change that, the governor’s office said.

“We haven’t seen bill language yet, but are hopeful that any expansion to the Empire State Child Credit will continue to include ITIN filers,” said Pete Nabozny, policy director of The Children’s Agenda. “We have no reason to believe that it will not.”

The proposal would also eliminate the phase-in component of the ESCC, meaning it would be fully refundable—allowing families to claim the full credit amount. Under the current rules, the lowest-income families are ineligible for the maximum credit, putting them at a disadvantage.

“The proposal does make some real structural changes to the way that the tax credit is formed,” said Kari Siddiqui, project director at the Schuyler Center for Analysis and Advocacy. “So it eliminates what we call the ‘income phase-in’ component.”

According to poverty experts, New York is the only state with a refundable tax credit that also includes an income level phase-in, excluding low-income families from accessing the maximum credit and limiting its anti-poverty effect. But if the governor’s proposal is enacted, that would finally change.

Nabozny explained that families earning less than $9,667 currently don’t qualify for the full $330 per child credit, and families with multiple children must earn more and more to qualify for the full amount.

The governor’s proposal would eliminate the minimum income threshold to receive the full credit. “That, in and of itself, making that structural change, really shifts the way that we’re thinking about and implementing our tax credit to make it more equitable and more targeted towards low-income families,” Siddiqui added.

Researchers at Columbia University’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy have recommended such a change for years, as have previous progress reports by the New York State Child Poverty Reduction Advisory Council (CPRAC). The council is charged under the state’s 2022 Child Poverty Reduction Act with making policy recommendations to cut child poverty in half within a decade.

And while advocates welcome the proposed increase, they also recognize that there is much work ahead. According to the governor’s proposal, the tax credit expansion alone would reduce child poverty in the state by 8.2 percent.

Other proposals on Hochul’s agenda include free school breakfasts and lunches, subsidized child care, and an inflation refund check. These, “ when combined with other measures already advanced by Governor Hochul…will see child poverty reduced by 17.7 percent,” reads a press release from her office.

However, researchers see the one-time inflation refund checks as a popular proposal, but without much power to reduce systemic poverty. It doesn’t adjust for family size, only by filing status: $300 for individuals earning less than $150,000 a year, and $500 for married couples and heads of household earning less than $300,000 a year.

“We believe families struggling with affordability in New York would be better served by a larger Empire State Child Credit expansion and investments in other priorities like child care and affordable housing,” Nabozny said.

Hochul’s proposal resembles one of the items in CPRAC’s secondary recommended policy package, but hers is slightly different from what the council suggested. The CPRAC report called for increasing the maximum ESCC to $2,000 for children under 6 and $1,500 for children 6 years and older, which it said would reduce child poverty by 25.5 percent. Hocul’s proposal would give smaller amounts, with the maximum for families with children under 4.

“When it comes to child tax credit policy design, we know from our research that larger credit amounts, full refundability (i.e., no phase-in or earnings requirement), and higher phaseout thresholds lead to the largest reductions in poverty,” Vinh said in an email. “With [Hochul’s] proposal, New York would be among the states with some of the largest state-level child tax credits, and it is designed to reach all children in poverty.”

According to the most recent data from the Schuyler Center For Analysis And Advocacy, children under the age of 4 make up about a quarter of the children living in poverty in New York State, who at the same time, are most positively impacted by these kinds of investments and supports, according to research.

Nabozny recommended including 17-year-olds, increasing the credit for children 4-17 above $500, and implementing the entire proposal in one year instead of two.

Advocates also agreed on indexing the credit to inflation as a way to more permanently eradicate child poverty. “Updating the credit amounts for inflation each year could ensure that the impact of these credits does not diminish over time,” Vinh said. “Additionally, even higher credit amounts in the future could yield even larger reductions in poverty.”

Another CPRAC recommendation was housing reform: The council called for creating a state-level housing voucher based on the Federal Housing Choice Voucher Program, allowing eligible New Yorkers to apply regardless of their immigration status.

For several years, advocates and legislators have proposed a subsidy designed to help homeless New Yorkers secure permanent housing, called the Housing Access Voucher Program (HAVP). When analyzing poverty reduction by location, a voucher program would be one of the largest single policies to reduce poverty for all ages in New York City, reducing it by 12.5 percent, according to the CPRAC report.

Advocates for immigrant New Yorkers have included HAVP among their top priorities for lawmakers this year. It remains, however, a proposal the governor continues to dodge and to which she makes no reference in her 126-page “State of the State 2025” book, which also does not mention migrants or asylum seekers, who have been arriving by the thousands since the spring of 2022 and who view the incoming Trump administration with trepidation.

“Governor Hochul must drop her inexplicable, years-long opposition to the Housing Access Voucher Program, which would immediately help New Yorkers statewide to avoid evictions and move out of shelters into permanent housing,” the Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development said in a statement.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Daniel@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.