As city lawmakers negotiate a package for the “City of Yes” zoning reforms, a report from the Independent Budget Office highlights the importance of city subsidies in creating deeply affordable housing.

Adi Talwar

An affordable housing development sites in East New York, Brooklyn.As “City of Yes” for housing nears a vote in City Council, lawmakers are deliberating how the zoning reform package should address the need for apartments affordable to low-income New Yorkers. A new report from the Independent Budget Office (IBO) suggests city subsidy funds play a crucial, complementary role in financing deeply affordable housing.

City of Yes for Housing Opportunity, Mayor Eric Adams signature housing proposal, seeks to spur residential construction by loosening zoning regulations in neighborhoods across the city. The Council’s Zoning and Land Use committees, due to convene Thursday morning, will consider modifications to the mayor’s proposal, which advanced through the City Planning Commission earlier this fall.

The city allocated a record $26 billion for affordable housing development over the next 10 years in the most recent budget, but some advocates and lawmakers see City of Yes negotiations as an opportunity to secure more.

City lawmakers are pushing for a larger deal that may include capital funding for affordable housing development as part of the agreement, according to sources familiar with the negotiations—but the situation remained fluid as of Wednesday night.

The IBO report, released Wednesday finds that under de Blasio- and Bloomberg-era zoning incentives like voluntary and mandatory inclusionary housing, which require developers to include affordable units in exchange for more density, buildings often relied on direct public subsidy in addition to zoning and tax relief.

“Density bonuses alone have not driven deep affordability,” the report said.

One component of the Adams’ administrations proposal, the “universal affordability preference,” would incentivize developers to create affordable homes by letting them build more total units as long as they’re income-restricted, designed to work in tandem with the new 485x tax credit.

“‘City of Yes’ has been carefully crafted to complement state tax policy, delivering more housing and more income-restricted affordable housing than either policy could deliver alone,” said a spokesperson for City Hall in a statement. “The IBO’s newest report shows the need for a comprehensive, all-of-government approach to housing affordability, and that’s exactly what we are delivering.”

While proponents argue “a little more housing everywhere” will mediate overall prices, some city lawmakers have said the proposal doesn’t do enough to address housing affordability directly.

In a counter-proposal released earlier this month dubbed “City for All,” City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams called for deeper affordability targets for new housing production, increased funding for affordable housing development, and for affordability mandates to be included in the proposal’s transit-oriented development and town center zoning provisions..

“New York City is facing an affordability and housing crisis that requires the creation of new housing, especially homes for low-income families,” a spokesperson for Council Speaker Adrienne Adrienne Adams in a statement Wednesday.

Emil Cohen/NYC Council Media Unit

Council Speaker Adrienne Adams at the body’s pre-stated meeting on Feb. 8.“We know that creating affordable housing demands city support, and the Council’s City for All plan tackles this need by calling for capital funding into existing programs to achieve that goal,” the spokesperson added. “The Council continues to negotiate for the investments needed to truly tackle our housing crisis and the ways it impacts New Yorkers.”

Some housing advocates have joined calls for deeper affordability in the plan, while others have warned not to pin all hopes to zoning changes alone.

“If we are trying to look at the needs of people that are currently in shelters, in eviction proceedings, the populations that are bearing the brunt of the housing crisis right now, market rate housing is not accessible to them,” said Emily Goldstein, directory of organizing and advocacy at the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development.

Additional subsidies would help create housing at the deepest levels of affordability, according to Howard Slatkin, executive director of the Citizens Housing and Planning Council. But affordability levels are a balancing act, he added: requiring affordability too deep could limit how much gets built.

“Zoning doesn’t build housing, dollars build housing,” said Slatkin. “You can’t really increase the amount of subsidized housing that we build without increasing the amount of subsidy.”

And zoning reforms should be flexible enough so projects pencil out even if there isn’t enough subsidy to go around, Slatkin argued. “If you condition the zoning on the availability of subsidy, then you’re back in that zero-sum game, where given the amount of subsidy available there’s a cap on the amount of housing you can build,” he said.

Under Mayor Adams, the report says, new affordable construction has kept pace with the de Blasio administration.

From 2017 to 2023, 50 percent of all mandatory inclusionary housing projects received city subsidies as well. That funding allowed inclusionary projects to build units affordable to “very low” and “extremely low income” New Yorkers, like a family of four that makes less than $77,650.

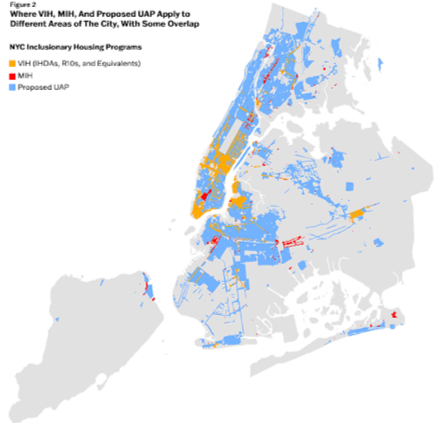

NYCIBO

The areas in blue would be eligible for the proposed Universal Affordability Preference option. The yellow shows areas covered by the city’s existing VIH program, and the red by MIH.“In 2023, two-thirds of directly subsidized units financed without inclusionary housing were reserved for extremely low-income and very low-income households,” the report said, compared to “30 percent that received inclusionary housing benefits and no subsidies.”

The area affected by the universal affordability preference (UAP) is much larger geographically than either of the previous zoning incentive programs studied.

The math to build affordable housing in other parts of the city is harder, according to the report. “If UAP is passed, some UAP projects will likely require City subsidies to be financially feasible, particularly to develop in weaker rental markets and to reach deeper affordability levels,” IBO says.

City of Yes supporters say that the UAP is designed to work with the new 485x subsidy program, which, instead of providing direct subsidy, provides tax exemptions to developers building affordable units, with less stringent requirements outside of the city’s highest density areas.

Advocates and lawmakers appear in agreement that every neighborhood needs to contribute to producing housing New York City needs—but the devil is in the details.

“We’ve seen from past programs that years later folks in government look back and realize there was an opportunity to do more,” said Goldstein.

To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.