“Rising unaffordability, worsened by a global pandemic, has created a cycle where many Black and brown New Yorkers, along with other marginalized groups, see leaving the city as their only option.”

Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office

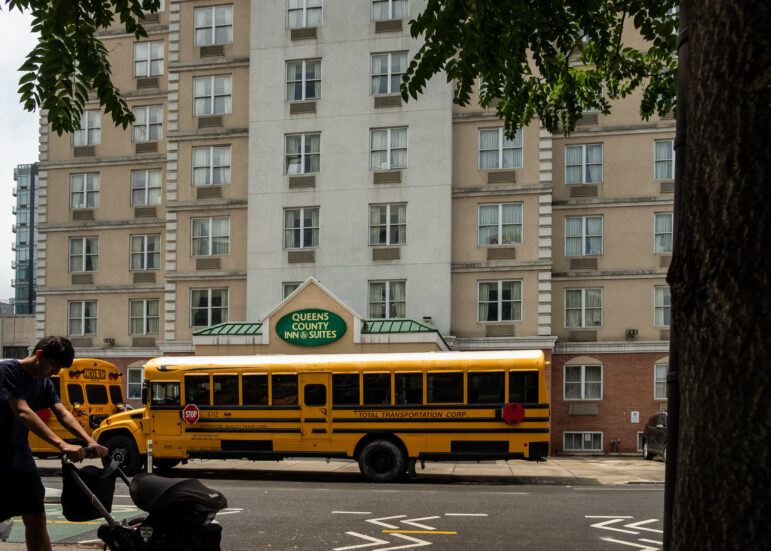

NYC students lined up for the first day of school in 2021.As another school year begins in New York City, so do conversations on how to make a school system serving nearly 1 million students more effective in providing a high-quality, equitable, and inclusive education for all. While many educational justice advocates rightly focus on issues within the purview of schools, I also recognize a need to broaden the conversation to include another critical social sector—housing.

This year marked the 70th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, offering a moment of reflection for organizations working to address school segregation. While it’s crucial to recognize the progress made, we must also confront the challenges that still impede true integration in our schools—including the impact of residential segregation and the legacy of redlining.

One such example of their intertwined history is the effect housing affordability and unaddressed historical neighborhood divestment have had on student enrollment trends across the city.

Affordability—in particular housing and the cost of raising a family—is increasingly driving population loss across the entirety of New York State. Households with young children are more than 40 percent more likely to leave the state, and twice as likely to move out of New York City, as households without young children.

The affordability crisis has a twofold effect on our school system. It has led to the hoarding of resources and opportunities in affluent neighborhoods, making them largely inaccessible to low-income families and historically marginalized Black and Latino families. Simultaneously, it has continued to compound on the legacies of redlining, concentrating divestment in historically Black and brown neighborhoods. Rising unaffordability, worsened by a global pandemic, has created a cycle where many Black and brown New Yorkers, along with other marginalized groups, see leaving the city as their only option.

Between 2012 and 2022, public school enrollment in New York City declined by 12 percent. Enrollment declines, and out-migration trends, are particularly stark amongst Black students— enrollment has declined by 32 percent over the same time period. As a result, school utilization rates in historically Black and Hispanic neighborhoods like Central and Eastern Brooklyn and the South Bronx are declining, raising concerns about the financial sustainability of those schools. Notably, these underutilized areas often overlap with those marked in red on housing redlining maps from the late 1930s.

These trends underscore the urgent need to address segregation in both schools and communities. The historical persistence of these invisible boundaries calls for a level of intention and effort that matches the forces sustaining them.

While direct efforts to address segregation in schools have not received the required attention for change, we are encouraged by the current administration’s commitment to forwarding a housing plan. Specifically, the City of Yes for Housing Opportunity, a proposed package of reforms that would ease barriers to adding new housing that is expected to be voted on by the City Council later this year, would move to ensure every neighborhood in New York City is doing its part to affirmatively further housing and address segregation head-on.

Between 2014 and 2021, nearly half of New York City’s 51 council districts produced fewer than 500 affordable units, compared to thousands of new units added to historically Black and Latino neighborhoods in the Bronx and Brooklyn. This is a pattern—low-density, affluent neighborhoods rely on restrictive zoning while communities of color carry the weight of adding new housing.

City of Yes has tailored strategies for all neighborhoods to add new housing while reflecting communities’ needs. Low-density neighborhoods could add new multi-family housing near transit hubs or on top of existing commercial corridors. In high- and medium-density areas like the Upper West Side of Manhattan, City of Yes would increase the amount of affordable housing by encouraging developers to grow a building’s footprint only if the additional units of housing are permanently affordable.

City of Yes naysayers may say that adding new housing will only exacerbate challenges such as overcrowding in classrooms, but this rests on two flawed assumptions: that school and housing advocacy remain siloed and that policymakers continue to allow the concentration of educational opportunities in a handful of schools. It also assumes noncompliance with the recent law lowering class sizes.

We’ve been ready to turn the page on our troubled history of segregation. While many education advocates remain disheartened by the lack of focus on school policies that could further integration, Appleseed finds a silver lining in forward-looking policy changes, like the City of Yes that showcase potential for New York City to be a more functional, affordable, and livable place for generations to come.

Nyah Berg is the executive director of New York Appleseed, which advocates for integrated schools and communities in New York City and New York State.

One thought on “Opinion: How NYC’s Housing Shortage Drives School Segregation & Disinvestment”

How can there be a housing shortage when, at least in Queens, numerous blocks of stores, restaurants and other small businesses have been closed, buildings demolished and big, ugly structures put up for apartments, the majority of which look empty?