A new state law requires New York City marshals to post notices of eviction to the state court website, in addition to serving them in person. Several marshals posted them late—or not at all—according to City Limits’ review of a sample of September eviction notices. Some lawyers say it’s a violation of tenants’ due process rights.

Adi Talwar

People entering Brooklyn Housing Court at 141 Livingston St. on the morning of March 20, 2023.Luis Compres, like many New Yorkers, saw his life upended by the pandemic. His small food service business, already just scraping by, went under. He struggled to get back on his feet, falling behind on rent while supporting his 12-year-old son and adult daughter, who live with him in a one bedroom apartment in the Bronx.

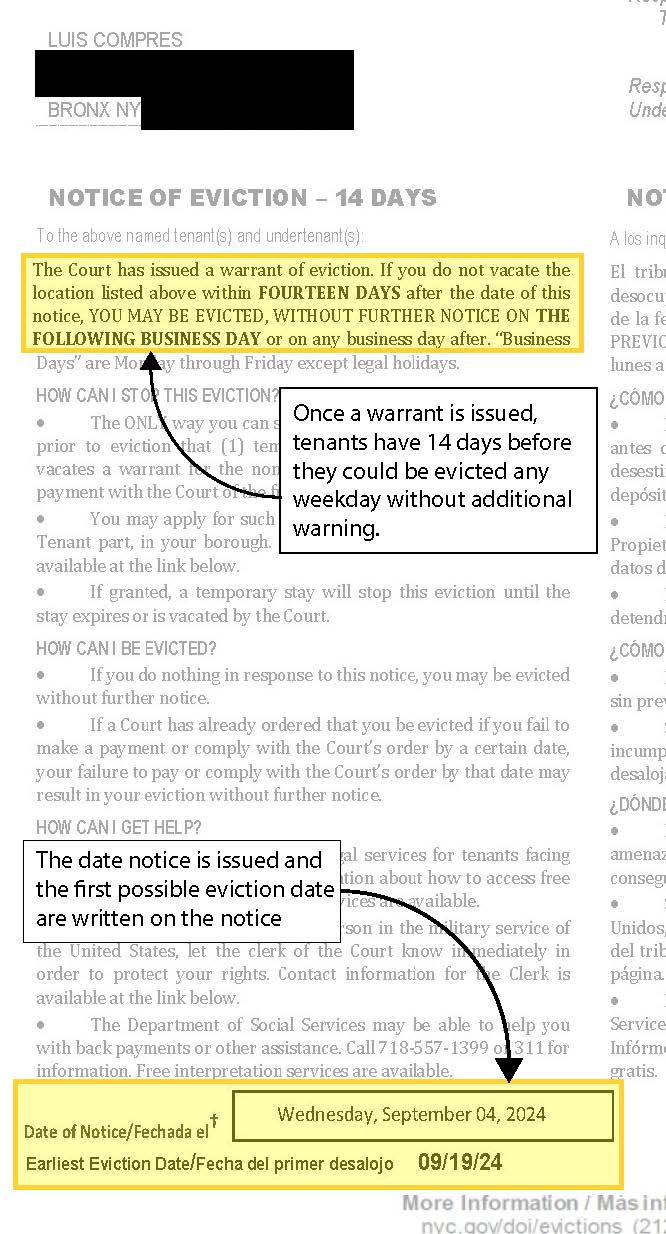

Eventually, he got a job as a chef in 2022 and could afford rent again. But his landlord had already filed for eviction. While applying for rental assistance to cover his remaining $20,000 in back rent, Compres was served with an eviction notice by Marshal Justin Grossman on Sept. 4.

An eviction notice is just that: a written warning, mailed to tenants and served in person, that after a 14-day waiting period, they could be evicted at any time. Beginning in late June, there was an added wrinkle: the State of New York now requires that notices of eviction also be posted to the New York State Courts Electronic Filing system, or NYSCEF, in addition to the traditional paper, in-person service.

The new regulation was passed by lawmakers at the end of this spring’s legislative session in Albany, an effort to make it easier for tenants, their representation, and housing advocates to know when an eviction is happening.

Marshal Grossman’s office didn’t post Compres’ notice of eviction to the NYSCEF portal until 11 days later on Sept. 16, 72 hours before Compres could have been evicted.

A City Limits review of 537 eviction notices served over a two-day period in mid-September revealed inconsistent compliance with the new requirement, with some notices posted within 24 hours of paper service, some posted after the first day an eviction could have taken place, and in some cases, not posted at all. Marshals executed at least two evictions without notice ever being posted online.

The timeliness of posting online notice, and the additional right for tenants to be notified that way, remain an open legal question as marshals, lawyers, and the courts determine how to enforce the new state mandate. The text of the law doesn’t specify when notice needs to be posted to NYSCEF, an omission tenant lawyers hope the courts will close.

Some tenant lawyers argue the failure to post notice contemporaneously with paper service constitutes defective service and a violation of tenants’ rights.

Thus far, the Department of Investigation (DOI), which oversees marshals, has not provided guidance on how to comply with the new regulation. In lieu of that guidance, housing courts have been hesitant to weigh in.

“The law, as written, is not precise and needs to be addressed with the various stakeholders so the marshals can have clear guidance about what they need to do to comply,” said Diane Struzzi, director of communications for DOI in response to written questions from City Limits.

Michael Woloz, a spokesperson for the NYC Marshals Association, said the law is “being defined by judges day to day.”

“We are all working together and sharing case law as it’s released to ensure that we can comply,” he said. Both marshals and DOI say that compliance is improving.

Thanks to a sympathetic judge, the new law did help Compres get more time to apply for rent relief. But with the law inconsistently enforced, some of the thousands of New York City tenants served with an eviction notice this summer might not have gotten the same opportunity.

“Marshals are sloppy and we want to hold them to it,” said Zachary Hale, an attorney and co-chair of the Brooklyn Tenant Lawyer Network. “Tenants are held to a very strict standard.”

Online service gaps

NYSCEF, Patrick Spauster

Getting an eviction notice had a devastating effect on Compres’ mental health. He contemplated suicide this past year, fearing that he would lose his home and not be able to support his children. “I don’t wanna be in the street,” he said. “I have so many [people] depending on me that I have to be strong.”

His lawyer, Payton Fisher of Mobilization for Justice, urged the court to stay Compres’ eviction. Marshal Grossman, he argued in a motion dated Sept. 20, did not provide Compres with proper service because he did not post the notice of eviction online in a timely fashion.

In a brief he wrote appealing to the Bronx housing court, Fisher argued that the “prejudicial lateness” of the notice denied Compres of his due process rights.

“The horse, so to speak, had already bolted. Closing the stable doors behind it does not bring it back,” wrote Fisher.

“The timing and completeness of the service matters,” emphasized Hale. The 14-day notice, he pointed out, kicks a legal defense into high gear, helping applicants expedite cash assistance or voucher applications and puts all hands on deck for attorneys and paralegals defending tenants.

Getting notice when it’s sent, rather than a few days later when a client comes home or finds it in the mail, adds “precious, crucial days, in the representation of someone in a crisis point,” said Hale.

City Limits reviewed files for 537 eviction notices served between Sept. 11 and 12, checking the state court system for notices of eviction and the dates they were posted. While they represent just a small sample of evictions, records confirm numerous cases of missing and late posting of eviction notices online.

Court and eviction records are accessible online, but data on when notices are served is not usually public. The data shared with City Limits comes from a “marshals activity spreadsheet” that DOI shared with legal service providers, according to multiple sources.

The spreadsheet is part of a new notification system for legal service providers that DOI rolled out in September. The spreadsheets, emailed to legal services providers, include data entered into a software system by marshals’ offices for all residential notices of eviction served upon tenants in the previous 48 hours, according to Struzzi. All notices on that sheet get served, except in instances where a case is discontinued or stayed before notice is served in person, Struzzi confirmed.

In all, marshals posted notices in 500 out of 537 instances; 293 of those postings came within the first day. On average, they were posted three and a half days after the tenant was served in person. But if and when marshals posted varied dramatically by which marshals office was responsible.

Marshal Grossman consistently posted notices well after serving in person, or didn’t post them at all for notices dated Sept. 11 and 12.

During those two days, Grossman’s office issued 123 eviction notices. Of those, he posted zero notices within the first week; 88 were posted between seven and 14 days after paper service, while 19 were posted after the first possible eviction date, 14 days later. Another 16 were never posted at all. Of all marshals who served notices in the two day period for which City Limits reviewed data, Grossman had the latest average posting date—11 days after the service.

Grossman declined to comment for this story, referring questions to Woloz of the Marshals Association instead.

“We do not comment on specific offices however, due to the timeline under which this law was enacted, each office did the best they could to comply with the directives of the law, notwithstanding various uncertainties and impossibilities that arose,” said Woloz when asked about Marshal Grossman’s postings.

Courts have not yet weighed in on whether late or defective online notice violates tenants rights under the new law. In individual cases where it has been raised so far, courts have generally left the issue alone or ruled on limited grounds to delay evictions, according to lawyers familiar with the decisions.

In a Sept. 27 decision, Queens Housing Court Judge Enedina Pilar Sanchez extended a stay on an eviction due to late online notice, writing that the tenants showed “good cause” to extend the stay: “the notice of eviction is vacated, the stay continues… for the service of a notice of eviction is required by law.”

But other judges, asked to stay evictions when online notice requirements weren’t followed, went the other way. In a Brooklyn case, Judge Jason Vendzules wrote that the “alleged violation of [the notice statute] does not justify the relief requested.” The notice was uploaded to the state court site between when the defendant asked for a stay and the judge ruled.

In Compres’ case, the argument that he wasn’t properly served in September helped earn him a stay, vital extra time that allowed him to expedite his application with the city’s Human Resources Administration for a “One-Shot-Deal”—cash assistance he used to help pay outstanding rent and stay in his home. With the case settled, the court didn’t rule on whether Compres was indeed properly served.

“We need the timeline,” said Munir Pujara, deputy director of the public benefits unit at Legal Services NYC, who emphasized the extra time is crucial to help people, especially the elderly and disabled, get benefits that can stave off eviction.

Compres expressed relief and gratitude that his case was settled in a phone interview with City Limits. But the toll of facing eviction lingers.

“You try to let it go, you can’t. I don't know how to explain that, because still I wake up in the morning or the middle of the night and I'm not right,” Compres said, noting how hard it is to stay afloat. “In order to support things, you gotta do two jobs seven days a week. It's not easy.”

Communication breakdown

Lawyers call marshals offices constantly. Sometimes tenants don’t get their paper notice and don’t know to show up in court, which can result in a default judgment in their landlord’s favor. Lawyers call to find out the first possible eviction date.

“There's a million reasons why a person wouldn't get a paper notice either, right? There's apartments that don't even have mailboxes or they have shared mailboxes or if it's one where they have to post it to the door, it could just fall off,” said Mobilization for Justice’s Fisher in a phone interview with City Limits.

Online posting, he said, “is a reasonable and very low intensity safeguard.” The online posting of notices would ideally cut out the need to call to find a copy of the notice, but when they aren’t posted promptly, lawyers say they end up calling anyway.

Evictions aren’t always scheduled for the first possible date after the 14-day notice period ends, so lawyers also rely on calling marshals offices to find out when an eviction is actually scheduled.

Multiple lawyers City Limits spoke to for this story said that since the new law passed, marshals offices have been resistant to answering their questions, pointing to the online notice requirement instead and saying lawyers can find out for themselves.

They noted that the service they get depends on the office and who answers the phone.

“Eviction dates are not finalized until the day prior to eviction; therefore, before the 14-day notice period ends, referring callers to the online posting may provide the most accurate timing marshals have,” said DOI’s Struzzi.

Marshals offices, Struzzi pointed out, should be responding about eviction scheduling when the 14 day notice period is up. “DOI was made aware of one complaint regarding this issue and handled the issue with the specific marshals’ office,” said Struzzi.

Some offices, lawyers told City Limits, are helpful in telling you when an eviction is scheduled, and will provide more than 24 hours notice, but others don’t provide such a courtesy.

“It’s very frustrating for attorneys generally that there is so much variability for everything from how they schedule to how much information they will tell you,” said Hale.

A spokesperson for the Marshals Association said their members did not receive advance notice from courts or DOI about the new law, which created “many issues” like the need to update their computer systems.

“Marshal’s offices are small businesses with limited staff. They are now complying with this new requirement and have been doing so while addressing the normal day-to-day operations of their offices,” said Woloz.

Marc Fader

A marshal's eviction notice, seen in 2010.“Marshals will comply with any new requirement put forward, but if given a more structured guideline with an advanced timeline they could be better prepared,” he added.

City Limits found that the pool of 537 notices served on Sept. 11 and 12 resulted in at least 128 executed evictions as of Oct. 23.

Two evictions—one on Grand Concourse in the Bronx and another on Seagirt Boulevard in Far Rockaway—that took place without notice ever being posted online. Marshal Edward Guida Jr. carried out both evictions on the earliest eviction date in late September (Guida Jr. declined to comment, referring questions to the Marshals Association).

Another eight evictions, all executed by either Marshal Guida Jr. or Marshal Grossman, were executed a few days after the 14-day notice period ended, but less than seven days after notice was posted online.

“I just don't understand why it takes this full court press to get them to do one extra little thing,” said Fisher, emphasizing that prompt notice can help prevent people from losing their homes. “It's like they have an interest in bending the rules because they get paid out whenever they execute an eviction.”

'The single most important piece of paper'

Lawyers, marshals, and DOI think compliance could improve with greater clarity on how to enforce the law.

Fisher and other tenant lawyers argue that notice needs to be posted on the same day as paper service, pointing to the bill’s sponsor memo, where Assemblymember Charles D. Lavine wrote, “this section requires marshals to provide contemporaneous notice by physical posting and electronic filing.”

“If we have a statute on the books that if you just read it, it says it should function a certain way and the courts ignore it, then what's the point of the statute?” said Fisher.

On July 18, three weeks after the law took effect, Floralba Paulino, chief investigative auditor for the DOI’s City Marshals Bureau, wrote an email obtained by City Limits notifying marshals of the new law.

“An advice letter will be issued by DOI… containing guidance on how marshals will upload Notices of Eviction,” the email read. “Marshals are advised to electronically file all Notices of Eviction served upon tenants as of the effective date of the amendment June 28, 2024.”

But DOI hasn’t issued formal guidance to marshals about how to comply with the new requirement, or when they need to post notices of eviction online.

“The law itself is silent on timing,” said DOI’s Struzzi. “DOI was not consulted on the final language of the law before it was passed.”

But the department is actively engaged in determining and providing clarity on the issue with various stakeholders, including courts, city marshals, the Legal Aid Society, and others, according to Struzzi.

“It is for the courts to determine what constitutes sufficient service in each case. DOI takes no position on that issue, but maintains that marshals must follow the law as enacted by the Legislature,” she said.

Lawyers want the courts or DOI to give the law more teeth. Some tenants, of course, don’t have lawyers at all to check the online court docket on their behalf, and might not be tech savvy enough to check it themselves.

In theory, the new requirement works in tandem with New York City’s right to counsel, which promises free legal help to low-income tenants facing eviction. But the program’s reach has been limited by underfunding, what Legal Services NYC’s Pujara called a “missed opportunity.”

For now, attorneys and advocates hope to see more stringent compliance with the new notification rules going forward.

“We’ve been relying on a dark age system, relying on a piece of paper sent through the mail or posted on the door, that is the single most important piece of paper in the eviction case,” said Fisher.

This story contains discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know need help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988. There is also an online chat at 988lifeline.org

Had an interaction with a marshal or failed to receive your eviction notice? Email patrick.spauster@gmail.com or the editor at jeanmarie@citylimits.org.

Data notes:

City limits reviewed all 539 notices counted in this story on the New York State Unified Court System (NYSCEF), plus several other cases where electronic notice was at issue. The case numbers came from the marshals activity spreadsheet, maintained by the Department of Investigation, which was shared with legal services organizations as part of ongoing negotiations about how to enforce the law, according to multiple sources with knowledge of the matter. City Limits verified the authenticity of the spreadsheet by talking to lawyers at multiple legal services organizations where the spreadsheet was shared in internal emails and by confirming matching information in the spreadsheet with individual notices that were posted with the dates and names listed. DOI provided matching details regarding the spreadsheet sharing in written comments to City Limits. The spreadsheet was also shared as an exhibit in court filings.

The marshals activity spreadsheet contained the notice date, number and name of the marshal, court docket number, borough, and names of plaintiffs and defendants. The data encompassed 537 eviction notices with notice dates between Sept. 11 and Sept. 12, 2024. To find cases in the online court system, City Limits relied on the court docket number and borough. In cases where the court docket number and borough were incorrect or produced multiple possible case matches, City Limits additionally relied on the names of plaintiffs to identify cases. In two cases, City Limits could not identify a case number that matched the information on the spreadsheet. Those cases are excluded from this analysis. City Limits checked cases for online notices between Saturday, Oct. 12 and Saturday, Oct. 19. Notices posted after Oct. 12 may not be represented in totals here (though any notice posted after Oct. 12 would be well after the first eviction date in any of the cases examined).

To identify the date posted, we use the posting date on NYSCEF for the eviction notice document. To identify the days since posting, we subtracted the notice date from the online posting date from NYSCEF.

Some cases had multiple defendants living at the property, who were each served their own eviction notice. In tabulating statistics for this story, we count notices, not cases, meaning there are fewer cases than notices in the period examined. Most of the time, notices for the same case are posted at the same time.

Some cases also have more than one notice served over the life of the case. Some of those notices have notice dates before or after the sample we looked at beginning Sept. 11. Often, these cases are still active because a notice is filed, but a stay or other legal proceeding prolongs the case. We checked the NYSCEF portal for only eviction notices matching the date on the marshals activity spreadsheet. Notices from previous or successive warrants are not counted.

City Limits determined if an eviction had been executed by matching the case number on the Marshals spreadsheet to the city’s eviction database on Open Data. We use the “at least” terminology when counting evictions because it’s possible City Limits is missing evictions that have taken place, but have data entry errors in the case numbers in the marshals activity spreadsheet.