New York City officials secured agreements from Uber and Lyft to “drastically reduce access restrictions” for drivers. But the New York Taxi Workers Alliance called the deal “a corporate give-away” that doesn’t do enough to improve workers’ conditions.

Melanie Gonzalez, Subrina Singh

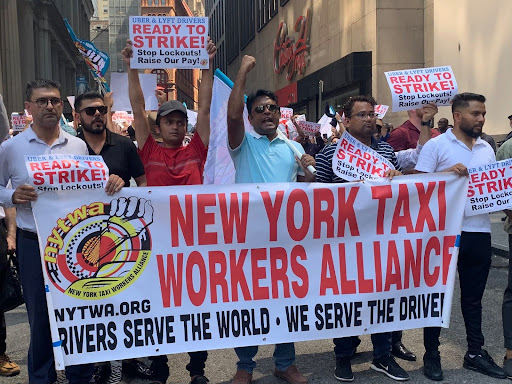

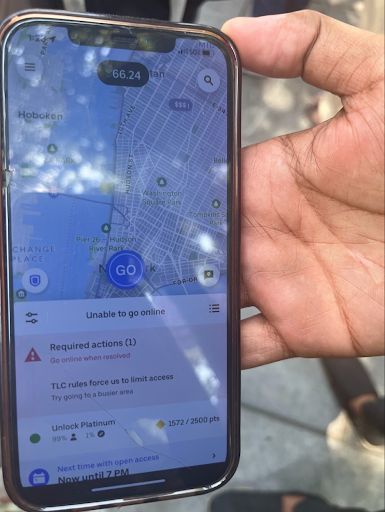

Left: Uber and Lyft drivers rallying against the lockout policy outside City Hall on July 17. Right: A driver displays how a lockout looks on the app.This story was produced by student reporters in City Limits’ CLARIFY News program.

New York City officials secured agreements from Uber and Lyft to “drastically reduce access restrictions” for drivers—referred to as “lockouts”—according to an announcement from City Hall Wednesday. But the New York Taxi Workers Alliance (NYTWA) called the deal “a corporate give-away” that doesn’t do enough to improve conditions for drivers.

Under the terms of the agreement, Uber will immediately “begin phasing out access restrictions for drivers using its platform,” with a goal of ending them entirely by early September as long as the company’s rival, Lyft, “maintains an annual company utilization rate (the time drivers spend with a passenger) of at least 50 percent.” Meanwhile, Lyft will “minimize lockouts,” according to the agreement. Both companies will pause onboarding for new drivers.

“The deal we’ve secured today will put money in the pockets of hard-working drivers and help them continue to afford to live in the greatest city in the world,” New York City Mayor Eric Adams said in a press release last week.

But the NYTWA, which represents both taxi drivers and drivers for ridesharing apps, called the deal a “betrayal” and said City Hall is “turning its back on drivers and letting these companies walk all over them.”

“This ‘deal’ won’t resolve the immediate crisis that drivers are facing,” Bhairavi Desai, the co-founder and executive director of NYTWA, said in a statement.

“Lockouts will continue for all drivers until at least the fall, and they’ll be especially pronounced for drivers who rely exclusively on Lyft for income. There’s no compensation for income that drivers have already lost, and no guarantees that lockouts won’t resume at some point even this year at full scale,” Desai added. “Moreover, this deal gives Uber and Lyft a free pass for manipulating the utilization rate for at least an entire quarter of this year.”

The deal between the city and the rideshare companies comes after a rally earlier this month, where hundreds of for-hire vehicle drivers gathered in protest outside of City Hall over Uber and Lyft’s recent practice of denying workers access to the app at times of low demand.

The “lockouts” practice prevents drivers from using the apps to pick up customer fares. The NYTWA claims that Uber and Lyft are doing this in order to avoid paying workers based on the Taxi and Limousine Commission’s minimum payment formula, which requires drivers to be indirectly compensated for time waiting for trips or on their way to pick up passengers.

The commissioner of the Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC), the city agency that regulates taxis and for-hire drivers, said in a press release that the agency’s priority is to “provide relief to the city’s drivers as quickly as possible.”

“This deal is the shortest possible path towards that relief,” TLC Commissioner David Do said. “At the same time, we have prepared a robust rule package designed to disincentivize access restrictions, and we are absolutely prepared to introduce that should it become necessary.”

At the driver-led rally on July 17, the NYPD reported that about 350 drivers showed up to speak on the issue and raise awareness. However, the NYTWA claims that closer to 2,000 drivers attended the protest. Members of the NYTWA led the charge, and City Councilmember Shekar Krishnan, along with State Assemblymember Zohran Mamdani, also spoke out on behalf of drivers at the rally.

Uber and Lyft drivers rallied in Manhattan on July 17 calling for an end the to “lockouts” practice.

Photos by Andrew Vera and Melanie Gonzalez.

Following impassioned remarks from drivers and advocates that began at 1 p.m., the NYTWA led a march down Broadway to Zuccotti Park around 2 p.m. Drivers flooded the streets as they chanted “driver power, union power, shame on Uber.” Some of the protesters heckled passing rideshare drivers who were not participating in the protest.

“We are starving,” said Javed Tariq, co-founder of the NYTWA. “Uber is making billions of dollars of profit off the hard work of Uber drivers. It’s a sweatshop on wheels.”

Desai said the lockouts are affecting over 80,000 drivers and their families in New York City and causing “financial crisis.”

“They’re trying to lock out drivers out of a living wage,” Desai said.

In 2018, the TLC implemented a law requiring ride-hailing companies to pay their drivers based on a new rate, the equivalent to around $17.22 an hour after expenses. This rate encompasses their pay during both active driving time and the time between picking up customers, known as “empty time.”

But in 2023, TLC changed the payment formula, resulting in an average annual pay cut of $5,000 for drivers, according to the NYTWA.

In March, the TLC raised the minimum per trip pay by 3.49 percent to compensate for inflation. The city claims that “the new pay rates will amount to almost a dollar extra for a typical 30-minute, 7.5-mile trip.”

Both Uber and Lyft have blamed TLC’s rules for necessitating the lockouts, including a required 53 percent utilization rate—the percentage of on-duty time that a driver has a passenger in tow—that the industry must meet on average.

A Lyft spokesperson said the rideshare service has been advocating to further change the pay formula.

“The current NYC pay formula is broken because the way it measures utilization works against drivers, not for them,” a Lyft spokesperson said. “It forces rideshare companies to limit when drivers can earn, and therefore how much they can earn.”

There’s now a waiting list to become a Lyft driver in New York City, according to the company.

A spokesman from Uber said that they stopped onboarding new drivers in January, and said the TLC’s rule “lumps the industry together rather than holding each company accountable.”

The spokesperson said Uber is being penalized for low-utilization rates from Lyft.

“Uber was meeting the requirement on its own, but because Lyft was not and the rule takes the average, the industry fell below the requirement,” the Uber spokesperson said in an email. “As a result, we have to bring our utilization up even higher to make up for Lyft’s low utilization. To do so, we must more strictly ensure that supply on our app meets demand, which requires us to limit drivers’ access when there aren’t enough ride requests.”

Ginger Rogers

A driver shows a City Limits reporter how his screen looks during a lockout.Uber and Lyft lockouts can happen unexpectedly and vary in duration, according to drivers at the rally. Some said they’ve experienced lockouts for five minutes, while others have been shut out of the apps for over five hours.

During a lockout, drivers can still open the app and see a map, but are unable to take on a new customer. One driver showed his Uber app displaying a red warning label, with the text that reads “TLC rules force us to limit access.”

“I’m here because I’m not able to work when I want to work,” said Oltimdje Ouattara, an Uber driver since 2015. “So if I am not able to go online, I can’t get any money. So I can’t pay my bills, I don’t work, [Uber] is the only job I have.”

For many drivers, it’s a gamble, as they are forced to waste time and resources while remaining idle and waiting for the app to come back online. Drivers often aren’t sure whether they should wait around or just go home.

“They’re locking us out so they don’t have to pay us. They are abusing and exploiting us,” said Malang Gassama, a driver. “They’re stealing our money for themselves.”

The growth of ride-hailing apps in New York City has put financial strain on both taxi drivers and rideshare drivers, leading to tensions between the two groups. Eight professional drivers died by suicide in 2018, including some who were struggling to make ends meet.

Both groups pushed city lawmakers to limit the number of for-hire drivers on the road and create a minimum pay rate. The city passed a cap on the number of drivers in 2018, but lifted it in the fall of 2023 to allow for new licenses for electric Uber and Lyft vehicles. While a lawsuit soon halted the city from once again accepting new applications, the temporary allowance added more than 7,500 electric ride sharing cars to the city’s streets, the Daily News reported.

“Our union warned the TLC and the city last October that if they release [license] plates with no order, no sense of the number of new cars, that each driver would be left empty longer and there would be the threats of lockouts and deactivation,” said Desai.

In a sea of drivers advocating for a stop to the lockouts and a livable pay at City Hall, there was one voice at the rally who didn’t agree that Uber and Lyft are at fault.

Melanie Gonzalez

Drivers and NYTWA members rallied against the app companies on July 17.“This union [NYTWA] has been around for 26 years, and they do some good work but they refuse to do the real work of calling for the reform of the Taxi Limousine Commission,” said Raul Rivera, the founder of NYC Drivers Unite.

Rivera—who sported a “Trump 2024” red cap—argued the lockouts are happening as a result of TLC advocating for the minimum wage law, and for treating drivers as employees rather than independent agents. Equipped with a percussion instrument, Rivera loudly and verbally sparred with a few of the drivers in attendance.

While Rivera urged drivers to stand up to the TLC and “fight for your rights,” another driver shouted back, “I am fighting for drivers’ rights, not your rights. This is BS.”

In a letter sent to the TLC in June, NYTWA claimed the apps are using the lockouts “to make drivers look less empty when its utilization for 2024 is reviewed” at the start of 2025, to avoid having to pay more to meet the minimum required by the city’s formula.

The union says the TLC “must use the actual utilization rate to re-calculate driver pay rates,” which it says has averaged at 51 percent so far this year.

“The solution is easy,” said Desai. “The TLC can fix the utilization rule and Uber and Lyft can acknowledge that they mismanaged.”

With reporting by: Andrew Vera, Cesar Jimenez, Suhani Cuenot, Allen Mantilla, Jovanna Wu, Chloe Zi Ching Wong, Namarachi Okwuka, Mannat Kaur, Mujtaba Raja, Emmanuel Brown, Duncan Park, Subrina Singh, Melanie Gonzalez, Pierce Malter, Jayleen Torres, Ean Bermudez, Haja Ceesay, Anyeli Clemente, Saniyah Davis, Deanna Hayward, Dylan Hernandez-Abreu, Fatima Konneh, Giana Newball, Naheema Olatidoye, Akeelah Outland, Ginger Roger, Paww Susannah Scott, Erica Tillman, and Maya Wierciszewski.

To reach the CLARIFY editors, contact Julian@citylimits.org and Melissa@citylimits.org

One thought on “City’s Plan to Address Uber & Lyft Driver ‘Lockouts’ Won’t Resolve Crisis, Union Claims”

Given the ongoing dispute between the city, Uber, Lyft, and the NYTWA, what potential long-term solutions or compromises could be explored to address the underlying issues affecting drivers’ livelihoods?