Amid a steep rise in people living in shelter, few are exiting the system, and even fewer are getting housing placements, a City Limits analysis of public data shows.

Adi Talwar

Starlite Harris lived in the shelter system for about a year in 2021 and 2022, staying in eight different facilities. She has since moved into her own apartment after securing a CityFHEPS voucher.Starlite Harris lived in eight different New York City homeless shelters between 2021 and 2022, thanks to a series of transfers and health crises that required hospitalization.

“It’s more exhausting than it sounds,” Harris said.

Eventually, she received a rental voucher and found an apartment that accepted it in Williamsburg. But for many, this outcome remains out of reach.

Data on shelter exits released by the City of New York beginning last year highlights just how narrow the path out of shelter is, and how hard it is for homeless residents—particularly single adults—to find permanent housing.

Through nine months of Department of Homeless Services (DHS) exit data from May 2023 to January 2024, an average of 10 percent of households in shelter left the DHS system each month, and just 2.6 percent exited to permanent housing.

Over the 12 months ending last June, DHS shelter residents had spent more than a year on average in the system. That’s even after average stays decreased nearly 20 percent from the year prior for most households—a change Mayor Eric Adams’ administration attributed to increased housing placements and an influx of asylum seekers with shorter stays overall.

People end up “stuck” in shelter, Harris said: “I just don’t feel like anyone should be in a place like that for more than a year.”

Among those who do exit shelter, where they go is often a mystery: an “exit unknown” as it’s tagged in DHS’ data system, accounting for over half, or 55 percent, of households who left shelter during nine months City Limits analyzed.

This group—which includes most single adults leaving shelter and about a quarter of families with children—is more likely to stay homeless than find housing, advocates say.

About 38 percent of exiting families with children secured permanent housing with a rental voucher, City Limits found, compared to just 9 percent of single adults.

“The limited data provided by the administration illustrates how the shelter system is perpetuating the cycle of homelessness, rather than interrupting it,” said Councilmember Shahana Hanif, a sponsor of Local Law 79 that made this data available, in a statement to City Limits.

Amid a homelessness crisis where a record 150,000 people stayed in shelter in December 2023, according to City Limits’ estimates, data on exits highlights a system with an inadequate release valve.

And even as the shelter population declines modestly, it remains largely unclear whether those exiting actually find housing, move to a shelter operated by another city agency, or end up doubled up, on the street or, eventually, back in DHS’s care.

Advocates for the homeless are calling for more detailed data, and say additional support is needed for clients who move in, out of, and around the system.

Many entrants, few exits

How did we get here? For one thing, there simply isn’t enough affordable housing to go around.

Over the last several years, the number of households entering DHS shelters has far outpaced the number of people leaving shelter for housing, even as housing placements have increased—up 17 percent in Fiscal Year 2023, according to the Adams administration, and 16 percent in the first seven months of Fiscal Year 2024, through January.

At a city budget hearing on May 6, Department of Social Services (DSS) Commissioner Molly Park touted this progress, which she attributed in part to new rental voucher policies, like reduced paperwork and statewide applicability for City Family Homelessness and Eviction Prevention Supplement, or CityFHEPS, vouchers.

But Park also acknowledged the supply shortage. “It’s hard to find housing,” she said.

The gap between entrances and exits has also grown with the arrival of tens of thousands of new immigrants to the city since 2022, more than 30,000 of whom were living in DHS shelters as of March.

For a closer look at how New Yorkers are exiting shelter, City Limits examined exit data from DHS shelters only, where roughly two in three shelter residents live. The data does not include exits from specialized DHS programs like safe havens or stabilization beds.

The city does not report data on exits for all New York City shelters, like the Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Centers (HERRCs) where additional tens of thousands of recently-arrived migrants are staying.

Accessing a housing voucher is the most common route from shelter to permanent housing—58 percent of exits to permanent homes were by way of vouchers in the period City Limits examined, primarily CityFHEPS, the city’s rental subsidy program.

DHS says it is on pace to move 12,000 shelter households into apartments using CityFHEPS vouchers this fiscal year, up 20 percent from the year ending last June. In 2023, the Adams administration eliminated a policy that had required households to be in shelter for at least 90 days before becoming CityFHEPS-eligible.

But City Hall has so far refused to implement a suite of laws that would eliminate the vouchers’ work requirements and broaden income eligibility, among other reforms.

Discrimination against voucher holders is also a persistent issue. “There's just a lack of affordable housing and landlords and brokers that are willing to accept these subsidies,” said Jina Park, senior vice president of families with children services at HELP USA.

Measuring the unknown

In 2022, the City Council passed legislation requiring various agencies to overhaul how they report data on unhoused New Yorkers, including—with new granularity—how many exited shelter each month, by what means, and where they went. The data is published on a delay in a PDF on the city’s website that is overwritten monthly.

Most households exiting shelters aren’t getting a voucher, or a placement in a supportive or public housing unit. Some who leave report staying with family and friends, finding housing on the private market without a voucher, or entering medical care.

But overall, the city doesn’t know where the majority of people go when they leave the system: 56 percent of household exits were categorized “unknown” in reports published from May 2023 through March 2024, with data lags varying based on household composition.

Single adults exited unknown 64 percent of the time during this 11-month period, far more often than families with children, who exited unknown 25 percent of the time.

In written responses to City Limits’ questions, a DSS spokesperson emphasized that the agency has different approaches for single adults versus families with children.

In particular, they seek to maintain lower barriers to entry for service-resistant single adults who may cycle in and out of shelter as staffers work to build trust, which may account for a high number of unknown exits in that population.

At the May 6 budget hearing, Park of DSS described adults in shelter as a more “transitory” population that tends to “come and go” from shelter and is not required to report where they are, in part out of respect for privacy.

"If we placed somebody in permanent housing, particularly if it’s a subsidized permanent housing that we’re paying for, we do track that, and we know where they are,” she said. “But for people that make their own arrangements, that’s not data that we track on a regular basis.”

Those who exit “unknown” might double up with friends and family, switch to another shelter that DHS does not track, leave the city entirely, or end up on the street. But the gaps in the data make it hard to say for certain.

“There is a sizable number of people you just can’t really say. That remains an issue,” said Ashwin Parulkar, associate vice president of research at HELP USA who has been researching exits and movement within New York City shelters.

Shelter providers input data on clients who enter and exit in a city-run database, DHS CARES. But it was designed prior to passage of the Council law requiring more detailed data breakdowns and misses too much, Parulkar says, including movement within the system and more specific reasons for why people exit unknown. “The system is behind the mandate,” he said.

The responsibility of following up with and assisting clients after they exit shelter often falls to overtaxed shelter staff, who are trying to manage other cases and help place people in housing.

“In addition to the work that they're required to do, there's a need to continuously follow up with these clients. It's just sort of too much,” said HELP USA’s Park.

Migrants in shelter who either take the city up on its offer for a plane or bus ticket out of town, or—in the case of single adults and families without children—leave because of a shelter eviction notice, are included in the exit data as “other,” according to DSS, among other known exits that don’t fit in the listed categories.

The most common exit for families with children in City Limits’ review period was a housing voucher, accounting for about a third of those who left. But among families with children, unknown exits spiked in the latter half of 2023.

Experts say that rise can be attributed in part to the fact that many newly arrived migrants—over 29,000 of whom were living in DHS shelters as part of families with children as of March—must navigate obtaining asylum-seeking status and finding on-the-books work to be eligible for city housing programs.

“They're in a really bad spot,” said Seth Frazier, supervising social worker at the Urban Justice Center’s Safety Net Project.

High mobility

Households only need to spend a certain number of weeks outside of a DHS shelter to be deemed “exited”—two months for single adults and one month for families—making it difficult to track how many people end up returning to shelter after those time frames.

But Parulkar of HELP USA believes those who exit unknown are more likely to bounce between shelters, the street, or other temporary housing situations. They may leave out of frustration, or because they find a given shelter too harsh of an environment. Missing curfew or otherwise failing to return to shelter can also mean losing a placement. (DSS emphasized that filling vacancies is important to maintain capacity and meet right to shelter requirements.)

Housing specialists, or staff that help shelter residents apply for housing, can also be hard to get in touch with, advocates say. “[Shelter residents] don't feel like they're getting the help they need for housing and so they just get up and leave,” said Safety Net Project’s Frazier.

Shuffling between shelters within the DHS system, as Harris did, can make consistent communication more difficult.

“One of [the shelters] didn't help me at all. And the other one just gave me paperwork and said you have to do it on your own, and they didn't have a specialist,” she recalled. “And then when [the housing specialist] came in, she was right back out because she broke her foot or something. So it made it very difficult.”

DHS can transfer residents within its shelter network for a variety of reasons—if they need more intensive services, or if staff feel there are domestic violence, safety, or medical concerns—movement not reflected in the city’s exit data. A spokesperson for DSS said that transfers were particularly necessary for safety during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to manage shelter capacity during the migrant influx.

Harris was transferred on several occasions: when she returned to shelter from the hospital, when she got sick with an infectious disease, when she needed to move out of a traumatic situation, and when she needed to move to a facility that could better accommodate her medical needs.

While sometimes requested by residents, transfers can also be involuntary, and clients have limited recourse to challenge them and only 48 hours required notice. DSS emphasized that the city makes efforts to avoid interruption of services during transfers, for example by having caseworkers share some client information.

Still, moving shelters can be frustrating and time consuming. In addition to packing up one’s belongings, a person may have to fill out fresh paperwork and share personal information. (Even though single adults—unlike families with children—are spared repeating the full intake process.)

Dinick Martinez moved shelters four times in two years before landing her current placement, a single room in a hotel shelter in Long Island City. “Just [moving to] a different shelter… you still have to do paperwork, 50 pages [of] paperwork,” Martinez told City Limits recently.

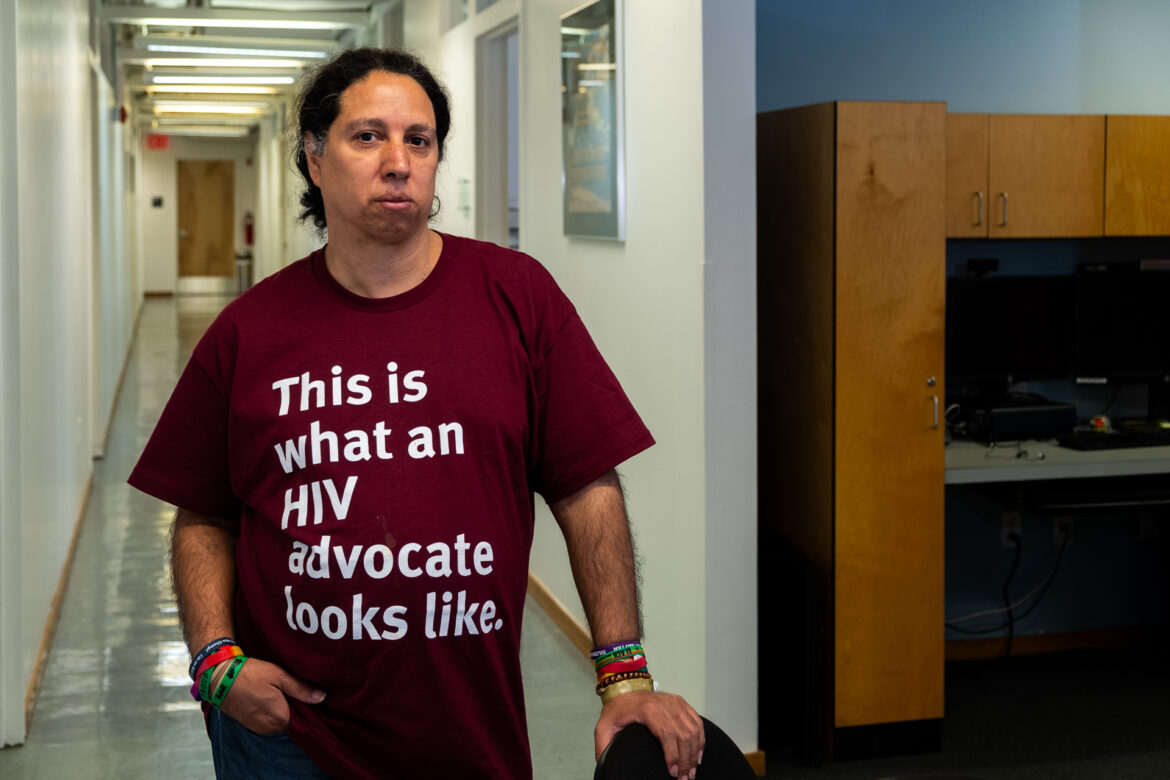

Adi Talwar

Dinick Martinez, pictured at Housing Works in Downtown Brooklyn, moved shelters four times in two years. Each move was a paperwork-filled process.Towards a better system

More accurate and detailed exit data, and more support for street homeless New Yorkers, could help the city better understand mobility around the system and reduce shelter recidivism, experts say.

“It allows you to target the right type of service for the right subpopulation at the right time,” Parulkar said.

Borough-based offices within the city’s Homebase program are intended to help families avoid homelessness by accessing rental assistance and finding lawyers to fight eviction, among other resources. They also help tenants renew their rental subsidies, according to DSS.

But the volume of unknown shelter exits highlights the importance of improving support not just for those with apartments, but for hard-to-reach clients who leave shelter without a housing placement, advocates say.

That could mean more street outreach. According to DSS’ Park, the Adams administration has doubled its outreach staff since taking office, to nearly 400. The city estimates that over 4,000 New Yorkers are street homeless as of January 2023.

Advocates would also like to see more support for voucher holders while they are in shelter, as they hunt for apartments. As it stands, finding an apartment even with a voucher in hand can take tremendous persistence.

Harris, for example, was eventually able to secure a CityFHEPS voucher with the help of a housing specialist. But she didn’t get much help when it came to actually searching for an apartment to take her voucher.

Helping clients find housing is a specific skill set, said Jamie Powlovich, executive director at the Coalition for Homeless Youth. Funding for more staff to help with the housing search would help relieve overburdened shelter workers.

“Giving someone a piece of paper is a success, but it doesn't always lead to the desired outcome because you need those wrap-around supports to ensure they can turn that piece of paper into a set of keys and actually move into an apartment,” she said.

After countless apartment viewings, calls, and follow-ups, Harris finally found her apartment in Williamsburg in February 2022.

“I got to the point where I got frustrated and I said, I'm not going to ask anybody [for help],” she recalled. “I'm just going to go out like I have a job everyday, and that's what I did. I got up every day, got out and went purposely looking.”

Editing and additional reporting by Emma Whitford.

To reach the editor, email Emma@citylimits.org and Jeanmarie@citylimits.org.

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.