While the Department of Social Services says more people were accepted into supportive housing last year than the year prior, a new report shows persistent barriers and rejections, including some that violate the city’s own guidance.

Adi Talwar

Kat Corbell, co-founder of Supportive Housing Organized and United Tenants (SHOUT), said she experienced a range of dead-end interviews before being placed in an apartment in 2019.By the time Corey O’Connor started sitting for interviews with supportive housing providers in August 2022, hoping to secure an apartment with accompanying mental health services, more than two years had passed since the pandemic upended his life.

In June 2020—shortly before he was laid off—his landlord shut down the dorm-style apartment where he and other flight attendants shared bunks. O’Connor then entered the New York City shelter system, where he learned that his post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis might qualify him for a low-cost apartment.

But the application process proved complicated, requiring everything from housing and work history to a psychiatric evaluation, with pitfalls like typos and incorrectly-checked boxes. “Ultimately I had to apply six times before getting approved,” O’Connor recalled.

The ordeal spanned more than 20 months, and that was just step one. Only with an approved application in hand could O’Connor face the next two steps in the process—referrals to interviews with housing providers, and the interviews themselves.

“There was just a lot of false hope going into each interview,” he said. “I would do these interviews, and even if it wasn’t my ideal apartment, I was so eager and desperate for an apartment that I would just say ‘yes, yes, yes’ and then would never hear back.”

O’Connor finally landed a placement in Harlem last November. In the shelter, he had been fearful for his safety, and was entirely preoccupied with finding a home. Now he could focus on medication management.

Outcomes like O’Connor’s are a stated priority for Mayor Eric Adams, who has said supportive housing is “where the money should go,” as the shelter system stretches to its limits.

But while the city is touting an increase in both available apartments and placements in the last year, a new report shows that bureaucratic hurdles persist. And while a supply and demand imbalance is at play—eligible applicants exceeded vacancies last year by the thousands—some people are being rejected in violation of city guidance.

By the numbers

There are currently about 37,000 supportive apartments in the city, most of them occupied. These units have restricted rents and come paired with support services for vulnerable tenants, including those who’ve experienced homelessness and people living with a mental illness, disability or substance use disorder.

During the most recent fiscal year, from July 2022 to the end of June, about half of the 8,235 individuals and families deemed eligible for supportive housing were subsequently referred for an interview. And just 1,787—58 percent of those interviewed and 21 percent of those eligible overall—were accepted, though not all had moved in as of June 30.

Mayor Adams has put special emphasis on finding apartments for street homeless New Yorkers. Yet only 26 people accepted last year were living in a public space at the time—14 percent of those eligible. (A broader “street homeless solutions” category cited by the city, including people in low-barrier shelters, saw 354 acceptances.)

The new data, anonymized and compiled by the Department of Social Services (DSS) under Local Law 3 of 2022, pulls from the city’s Coordinated Assessment and Placement System, known as CAPS, which tracks applicants and outcomes across 33,000 supportive apartments in the five boroughs, up from 27,000 tracked last year.

In a statement, DSS cited a 46 percent increase in acceptances reflected in the report, up from 1,224 last year. While this gain coincided with a 30 percent jump in the number of apartments tracked in CAPS, the agency said most of those units were already full when they were added to the system, and did not undermine the gains.

The city also touted its efforts to streamline the supportive housing lease-up process. The latest Mayor’s Management Report shows that the median number of days from application determination to move-in dropped about 9.5 percent year-over-year, from 169 days to 153 days, or roughly five months.

“More New Yorkers are now living safely and stably in supportive housing units because of our commitment to improving the entire supportive housing process,” DSS said.

But the Local Law 3 report details where others hit roadblocks. For example, in more than 950 instances last year, an applicant did not show up to an interview. Kate Barnhart, founder of New Alternatives, a nonprofit that helps homeless LGBTQ+ youth, said her organization has taken to escorting clients as an extra layer of support.

And to secure an interview in the first place, applicants must be referred. The Office of Affordable and Supportive Housing (OSAHS) within DSS makes most of the referrals, a process tenant advocates say is opaque.

At a City Council hearing in 2020, Jennifer Kelly, deputy commissioner of OSAHS, testified that her team considers factors including a person’s level of need and the services a provider offers, “trying to make a good match.”

Craig Hughes, a social worker with MFJ Legal Services who assists supportive housing applicants, said every step and waiting period in the process—down to the gap between being accepted and moving in, which the report doesn’t distinguish—is “another opportunity for everything to fall apart.”

Rejection reasons

Local Law 3 requires DSS to reveal how many people are rejected from supportive housing after an interview, including those who are subsequently accepted. All told, 675 households experienced a rejection last year, or about 21 percent of interviewees. Providers are not named.

Kat Corbell is co-founder of Supportive Housing Organized and United Tenants (SHOUT), a tenant union that advocated for the law’s passage. The group seeks to bring transparency to a system they say is overly burdensome and, at times, discriminatory, allowing providers to screen out applicants they deem too difficult.

Speaking to City Limits at St. Luke’s Lutheran Church Soup Kitchen in Midtown, where she volunteers, Corbell said SHOUT wants the public to understand the barriers to existing apartments at a time when policy talks often center on the need to build more.

Corbell herself experienced a range of dead-end interviews before being placed in 2019, for reasons logistical and less clear-cut. She was once sent to an apartment for seniors, despite being in her 30s. Another time, the interviewer seemed to think she had a drug problem and was in denial.

“I knew if I kept arguing with them or tried to assert myself it wasn’t going to go anywhere,” she recalled.

Both DSS and the Supportive Housing Network of New York (SHNNY), an industry group for supportive housing providers, emphasize the complexity of the existing network. Many apartments have funding requirements that specify the tenants they can accept—tied to age, income, the amount of time an applicant has been homeless and status as a veteran, among other characteristics.

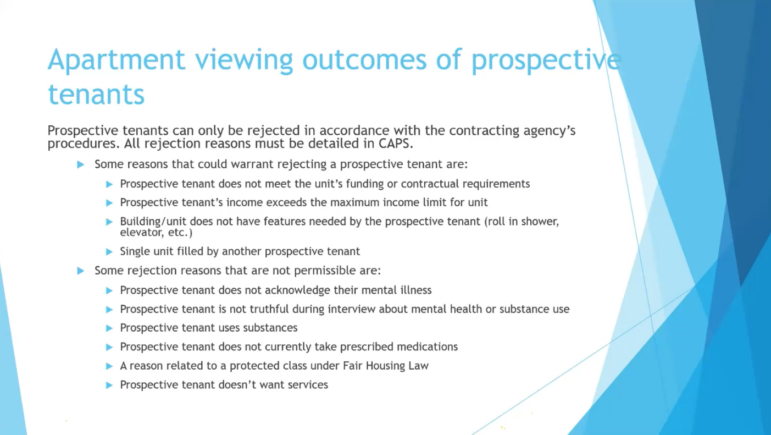

And since DSS often refers three prospective tenants per opening, some level of rejection is inevitable. This year, 230 rejections were attributed to “single vacancy filled by another client.” But the justification for denying housing is not always compliant with city rules.

During a recent training for providers, agency officials laid out inappropriate reasons for a rejection, including lack of truthfulness about one’s mental health or substance use; using a substance during the interview; not taking prescribed medication; or refusing offered services. The presentation also warned against Fair Housing Law violations.

“Having a mental illness or substance use history is why people are coming to us for help,” said Jamie Neckles, assistant commissioner with the Bureau of Mental Health within the city’s Health Department, during the training. “And so we really want to figure out how to meet those behavioral health needs, and not use them as a reason to reject a person’s placement.”

Examples of inappropriate rejections in this year’s report include one over “discrepancies with the interview and the psychosocial” regarding suicidal ideations. In another case, a client said they were “not interested in substance abuse treatment.” Another person is described as showing “little/no insight into her behaviors.”

Twenty-five rejections are attributed to lack of insight into mental illness. Twelve are categorized “drug/alcohol related,” and eight as “medication related.” Other apparently inappropriate rejections are detailed in a catch-all “any other reason” category.

One SHOUT member, who requested anonymity to protect their privacy, recalled an interview in 2014 when the provider cross-checked their statements about suicidal thoughts with medical history in their file. “Going in front of people to talk about some of your worst experiences in order to audition for housing isn’t helpful,” she said.

Pascale Leone, executive director of SHNNY, told City Limits that providers may lack the resources to support a particular applicant. Contract rates have long been a point of contention for providers, who say government funding does not keep up with their costs.

“Folks are presenting with more acute behavioral and physical health challenges that currently, as-funded, a lot of these programs are not equipped to meet,” she said.

“I just want to be very clear—discrimination of any sort is not tolerated, not accepted,” she added.

More than 120 rejections this year are categorized as “program does not provide level of service the client needs,” while nearly 90 are attributed to care, treatment and medication needs “beyond the scope of the facility.”

Such rejections are not discriminatory, DSS said, stressing that inappropriate placements can be detrimental to a tenant, as well as their neighbors and staff.

But Elizabeth Grossman, director of the Fair Housing Justice Center in Queens, said disability discrimination can occur if a provider does not explore ways to accommodate an applicant’s unique needs before rejecting them. She spoke generally as she was not familiar with the individual cases referenced in the report.

“Of course there is going to be someone who needs a level of care that is inappropriate for this environment, but we also hear from people who seem to be rejected based on stereotypes and unfair assumptions,” she said.

What’s in an interview?

Both DSS and SHNNY say this year’s supportive housing acceptance rate is best measured as a share of interviewees—58 percent. Some of those deemed eligible may end up pursuing other housing, according to SHNNY, perhaps using a rental voucher.

“You can’t... decline anyone who hasn’t been interviewed,” Leone said.

There are pros and cons to the interview stage of the process, she added. A tenant may reject an apartment of their own accord—perhaps due to the location, or the expectation that they live with a roommate—data not reflected in the Local Law 3 report.

“I totally hear the challenges of having that extra step,” she said. “But I also hear on the other end, from clients who went through the process. Being able to see the unit, and the value of that.”

But tenant advocates countered that acceptances as a share of all eligible applicants is a more important metric to track—21 percent last year. (Ideally, they say, the report would track how many tenants are securely moved into apartments.)

Barnhart of New Alternatives said that if one of her clients qualifies for supportive housing, she prioritizes landing them that placement over any other effort, including the voucher-assisted hunt.

“These people were approved for [supportive housing] because they need additional services,” she said. Because the stakes are high, an interview can feel less like an opportunity to ask questions, and more like a chance to leap at.

By the time O’Connor was offered an apartment last fall, he accepted it sight unseen. Only afterwards did he learn that he would be living in a building that was entirely supportive housing, rather than mixed-occupancy, which had been his preference.

But O’Connor said he’d learned a hard lesson following a prior interview, when a shelter staffer berated him for inquiring about a one-bedroom: “That’s when I was told you just say yes to anything.”

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Emma@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org.