The volume of cash assistance applications in New York City has increased dramatically in recent years. But as more households receive aid, the city is also issuing more procedural denials, in the hundreds of thousands.

Mayor Eric Adams’ administration isn’t only failing to process most requests for cash assistance on time—denials are surging as well.

The volume of applications has increased dramatically in recent years, a trend the Department of Social Services (DSS) has attributed to the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic and the lifting of policies that paused evictions during its peak.

Cash assistance includes both small, regular payments for the lowest-income New Yorkers, historically known as welfare, and larger, one-time grants for emergency needs like rent, also known as one-shot deals.

The city received 515,710 such applications in the year ending Oct. 1, a 67 percent increase from four years prior, city data show. The average number of households receiving cash aid, reported once per month, is also up over that period, by 33 percent.

Yet denials have increased even more dramatically, by 100 percent, totaling 287,280 over those recent 12 months.

When a person or family is denied cash support to cover life’s basic necessities, it doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t qualify for help, according to attorneys and advocates who specialize in public benefits. Rather, denials are often the byproduct of a bureaucratic gauntlet that can require multiple applications to successfully navigate.

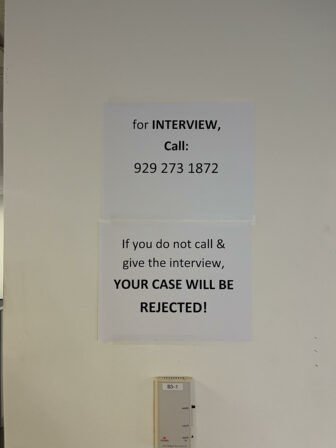

Each quarter, people are disqualified because they have too much income or lack a qualifying immigration status. But the denial reason issued most frequently by far is for failing to complete an interview—a step that became more involved when the city launched an online application portal and separate interview-by-phone process in 2020.

“It’s very hard to get through,” said Ced, a middle school teacher from Brooklyn. Ced, who requested that his last name be withheld to protect his privacy, fell behind on rent during the pandemic, while working as a substitute. Over the summer, he applied for emergency cash assistance to cover about $19,000 in accumulated arrears.

Once a person fills out the cash assistance application, they have 30 days to complete their interview, according to DSS. Over the phone, workers known as Benefits Opportunity Specialists—part of the Human Resources Administration (HRA) within DSS—are tasked with confirming information like a person’s identity, income and household size, and going over documents the applicant must submit.

But Ced described waiting for calls that never came. His initial attempts to use the interview line were also unsuccessful, resulting in two denials. “I tried for months to get in contact with HRA for an interview… but was never able to,” he said in a court filing.

In November, an eviction notice appeared on his door. The funds finally came through in December, saving his housing, but Ced felt the stress of potentially losing his apartment—“having to worry about what’s going to happen in the future.”

He is not alone. Interview-related rejections made up 45 percent of all cash assistance denials in the third quarter of 2023, exceeding 43,000. For comparison, in three quarters of data available before the pandemic, interview-related denials absent a scheduled appointment made up no more than 5 percent of the total. From October through December 2019, there were just 1,499.

Before the pandemic, said Legal Aid Society staff attorney Katie Kelleher, most of her clients would go to Benefits Access Centers across the city to apply for cash assistance. “They were getting an interview in person the same day they applied,” she recalled.

In a statement, DSS spokesperson Neha Sharma said that the agency made a crucial technological shift in response to the coronavirus. She urged New Yorkers to use its remote application tools as the city works “to continue to make it easier to apply for benefits online.”

Keeping up with increased demand has been challenging, Sharma said, but the number of households receiving assistance has increased—275,100 open cases as of September, city data show—proof that their processes are working.

“Despite unprecedented challenges following the lifting of key pandemic-related supports and the highest volume of cash assistance applications in well over two decades, on average more New Yorkers are receiving this critical benefit,” she stated.

The agency also launched an on-demand interview phone line in mid-April, touting an improved customer experience—cash assistance applicants can now call in rather than waiting for, and potentially missing, an interview. Those who don’t want to wait on hold can also request a call-back.

“While the wait times are long, people are not actually sitting on their phone or using up their minutes during that wait time,” Jill Berry, first deputy commissioner at DSS, said at a City Council hearing in November.

But challenges have persisted. In June, responding to a federal lawsuit over processing delays and denials, Berry described plans for a computer program to more expediently reject a “cohort” of cases in which applicants fail to complete their interviews within 30 days, despite receiving reminder notices—a “significant contributor” to the case backlog.

The program is now up and running, according to DSS. Deborah Berkman, a supervising attorney at New York Legal Assistance Group, questioned its helpfulness, saying that the city is more efficiently issuing denials resulting from “procedural hurdles that are almost impossible to comply with.”

Applicants, advocates and attorneys described a range of issues with the phones, including untenable wait times apparently exacerbated by short-staffing, missed call-backs and dropped calls, and general confusion about the rollout of the on-demand phone line, prompting people to wait for phone calls rather than proactively call in.

“It's more accessible, people don't have to leave their home,” said Charisma White of the Safety Net Project at the Urban Justice Center, a benefits recipient who helped push for 2019 legislation requiring quarterly reports on application denials. “But if you're going to use that service, you have to make sure it's working at top notch standards.”

Sometimes interviews are improperly logged, according to Payton Fisher, a staff attorney with MFJ Legal Services. “The client will have gone through with the call and I will reach out [to DSS] for an update and they’ll flatly say to us that the call never happened,” he said. “And they’ll issue a denial based on that.”

According to DSS, New Yorkers who prefer to apply in person can still do so. But even those who go to a Benefits Access Center are directed to a phone on site for the interview portion. This was the case on a recent Tuesday, at the Rider Benefits Access Center in the Bronx. Interviews must be conducted by phone, a security guard said.

Angela Wilkins was at the center that day to pick up a document. While DSS has touted its online and phone services for all case needs—there’s also an InfoLine for general information—Wilkins said these are not reliable, so she visits one of the DMV-like centers instead if possible. She summarized the interview line as “wackity, wack, wack.”

Kelleher of Legal Aid and her colleagues are part of the team suing the Adams administration in federal court over benefits processing issues. The fiscal year that ended in June 2023 saw just 28.8 percent of cash assistance applications processed within 30 days, down from 82.3 percent the year prior.

The share of cash assistance applications approved the same month they are submitted has also plummeted in recent years. The increased denials and delays are closely related, according to Kelleher, and are exacerbated by inadequate staffing at HRA.

“People apply and then nothing, crickets,” Kelleher said. Frustrated and lacking clarity, some just submit another application, she added. She suspects this is both adding to the backlog and necessitating certain procedural denials, as DSS workers must eventually close out duplicate applications.

Indeed, two other denial reasons used frequently in recent months, coded M66 and M67, apply if a person already has a pending application, or is receiving aid through another case. The codes are typically used to weed out duplicates, according to DSS.

In her June affidavit, Berry of DSS said the agency had seen a “sharp decline” in staffing due to retirements and attrition, and that the number of Benefits Opportunity Specialists processing cash assistance applications—at the time, called Job Opportunity Specialists—had been “significantly reduced.”

DSS has since hired aggressively, the agency said in January, and managed to boost the number of Benefits Opportunity Specialists by close to 50 percent, from 882 in January of last year to 1,304 in December.

But more staff are needed, according to Maikudi Okore, a Queens organizer with the Social Service Employees Union Local 371. “Some of the Benefits Opportunity Specialists don’t get to even have proper lunch time,” he said.

DSS recently increased the starting salary to $53,000, which is welcome, he added. But it’s still not high enough to be attractive to many potential applicants, given the high cost of living in New York City.

Meanwhile, since taking office, Adams has budgeted for fewer and fewer employees in the broader DSS “program area” that manages cash assistance, known as “Public Assistance and Employment Administration”—from 3,172 in 2022 to 2,657 this year.

After interview-related denials, document-related denials, categorized as “failure to provide verification,” are the second most common as of late 2023—about 11 percent of the total. According to DSS, applicants receive a notice and 10-day grace period to comply if they are missing paperwork such as a lease or birth certificate.

Another common denial reason, coded Y95, is unique to emergency assistance. It is used when an applicant doesn’t meet certain requirements, such as a demonstrated ability to pay back a rent grant. DSS stressed that certain eligibility criteria are set by the state and federal government, not the city.

Adi Talwar

People entering Brooklyn Housing Court in Mach 2023. Tenant attorneys say procedural cash assistance denials make their job of fighting evictions more difficult.In addition to his interview denials, Ced, the middle school teacher, said he received a third denial over missing documents, though he believes it was an error. “They said I didn’t have documents, so I put them back in [the system],” he told City Limits. “Curiously, this last time they had all my documents from all the times I put them in.”

This sort of confusion is not uncommon, attorneys said. When it comes to HRA, said Fisher of MFJ Legal Services, “The left hand doesn’t know what the right hand is doing.”

Even if an applicant makes a legitimate mistake, added Berkman of New York Legal Assistance Group, the error itself, or the path to resolve it, is seldom clear: “The process is confusing even for public interest attorneys.”

Okore, of Local 371, added that from the workers’ perspective, pressure to quickly reduce DSS’ case backlog can lead to mistakes. Experienced workers need time to train new hires, and share their knowledge. “When you’re working in that stressed environment, a lot of things get missed,” he said.

Joanna Laine, a staff attorney with the Legal Aid Society, represented Ced in housing court while he was fighting to get his one-shot deal. At any given time, she said, she has about 15 clients in a similar predicament, most of whom end up needing to submit multiple applications before they are ultimately approved.

Laine noted that the city pays her salary through the Right to Counsel program, which provides free legal assistance to low-income tenants facing eviction. The program is currently struggling to keep up with demand.

The city is working at cross purposes, Laine said: “Why are you making it so difficult to get the one-shot deal, that I have to spend so many of my hours advocating for a very simple application?”

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Emma@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org.

One thought on “‘Why Are You Making It So Difficult’? NYC Cash Aid Applicants Face Denial Surge”

The surge in denials for cash assistance in NYC highlights systemic challenges. Streamlining processes and improving access to support are essential to prevent vulnerable individuals and families from falling through the cracks.