As more young adults enter the city as asylum seekers, there is no official system in place to direct them to specialized shelters tailored to their needs—and, lately, no beds available even if they try.

Adi Talwar

People lined up outside the offices of Afrikana, a community center on Malcolm X Boulevard in East Harlem that’s been helping young immigrants navigate the city’s shelter system.When 19-year-old Mamadou Dian Bah arrived in New York from Guinea just over a month ago, he had no contacts, and no place to stay. He began sleeping in a mosque in the Bronx with other asylum seekers.

While visiting a volunteer-run help center for new arrivals in Harlem, he heard about a shelter specifically for young people like him. “They told me that if you find a shelter for young people, they’ll help you go back to school,” Mamadou said in French.

But his optimism disappeared when the Afrikana community center, which operates as a go-between for asylum seekers trying to navigate resources, informed him that there were no beds available at any youth shelter in the city. That night, Mamadou went back to the mosque, where he has slept every night since.

As a homeless young person under the age of 21, Mamadou is eligible for a bed in one of New York City’s 50 youth-specific facilities, which exist outside of both the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) family and adult shelter systems and the 210 newly set-up shelters for migrants.

Youth crisis shelters and longer term transitional independent living facilities offer a range of services tailored to the needs of homeless youth, such as facilitating access to GED programs and mental health services, and helping people transition to permanent housing.

But as more young adults enter the city as asylum seekers, there is no official system in place to direct them to these beds—and, lately, no beds available to receive them even if they try.

It’s these newly-arrived young adults, aged 18 to 20, who advocates say are falling through the cracks. Adam Bah (no relation to Mamadou), who runs Afrikana, is among those working daily outside of the city’s formal shelter placement apparatus to help people find places to stay.

“The city has specialized centers, but there are no beds,” she said.

Adi Talwar

Afrikana’s Founder and community organizer Adama Bah speaking with a client.Youth right to shelter

All adults in New York City have a right to shelter, under the terms of a 1981 consent decree, which the Adams administration is currently moving to suspend, citing the arrival over the last year and a half of more than 140,000 immigrants, more than 65,000 of whom are still in the system.

But New York has also recognized that young adults have unique needs, and thus, the city has a unique responsibility when it comes to sheltering them and providing services.

Specialized shelters under the Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD) offer beds to young adults aged 16 to 20. Just as adults’ right to shelter is governed by a court-ordered mandate, a 2020 legal settlement in a lesser-known case expanded the city’s obligations to homeless young adults, including a requirement to fund shelters as long as demand exists.

The agreement also guaranteed beds to 16- and 17-year olds. If the DYCD shelters are full, the logic goes, their slightly older peers can seek shelter in the larger DHS system.

The city currently offers 753 beds for people ages 16 to 20, according to DYCD. That system was already reaching a breaking point last year, and has not been expanded to accommodate newly arrived asylum seekers.

And now, another threat is looming: The legal settlement which has guaranteed funding for these beds since 2020 will sunset at the end of 2023, after which the city will no longer be required to fund DYCD shelters at the current levels, throwing the entire program in jeopardy.

DYCD has said that it will continue to fund all of the current beds in the system. But some advocates say the sunset of the settlement puts the long-term survival of the program at risk.

“Not only are there not enough services as is, but it will be the first time that, without jumping through a lot of hoops, the city will be able to cut runaway and homeless youth services, and that is very scary,” said Jamie Powlovich, who heads the Coalition for Homeless Youth, a statewide organization that represents the DYCD-funded shelter operators.

‘We are scrambling’

There is no process in place to identify DYCD-eligible youth among the thousands of new arrivals to New York City. According to advocates, all migrants over the age of 18 are currently being turned away from the city’s main shelter system and referred into the system of Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Centers (HERRCs), which is already overcrowded and offers no youth-only equivalent.

The only efforts to identify younger people come from volunteers and nonprofit workers who interact with new arrivals at ports of entry or community drop-in centers. When providers encounter someone under 21, they start calling around to the handful of city-funded youth shelters, hoping to hear about an open bed.

“It’s literally this informal,” said Powlovich, of the Coalition for Homeless Youth. Over the past month, dozens of young asylum seekers were referred to Powlovich for placement. But she had nowhere to put them.

“Right now, and for the past month on a nightly basis, there are no beds available,” she said. As the waitlist reached 100 names and no beds opened up, she stopped adding to it.

Adi Talwar

People waiting for assistance at the Afrikana community center, which has been aiding young newly-arrived immigrants.The city does not provide an age breakdown for asylum seekers, so it’s impossible to know exactly how many young adults are eligible for DYCD beds, and unable to access them. NYC Health + Hospitals, which manages intake processes, did not respond to questions about identifying newly arrived young people.

Bah, of Afrikana, thinks the city is not doing enough to help young adult asylum seekers. She is one of the people who call Powlovich nearly every day with a young person looking for shelter.

Afrikana operates out of a former restaurant and a makeshift office space in Harlem. From open to close, it is full of asylum seekers looking for assistance with obtaining IDNYC or MetroCards. Among the hundreds who pass through her doors, Bah identifies those under 21 and attempts to find them beds and connect them to GED programs, all while offering a place for them to hang out during the day.

Power Malu, whose group Artists-Athletes-Activists meets newly arrived asylum seekers at a church near Port Authority, says providers have been sounding the alarm to the city for months.

“We are hoping that the city can designate one site where youth can go to get robust services, so they don’t fall through the cracks,” said Malu. “Until that happens, we are scrambling and hoping that beds become available as we come across these youth. It’s just, fingers crossed.”

But DYCD has said there are no plans to add additional youth shelter beds.

“DYCD continues to work closely with our providers and agency partners to ensure that young asylum seekers in the city’s RHY [Runaway and Homeless Youth] system are supported along their immigration pathway,” said DYCD Spokesperson Mark Zustovich.

When asked how asylum seekers can access the system, DYCD directed the question to City Hall. A spokesperson for City Hall did not answer questions about young adults specifically, but said in part, “We have used every possible corner of New York City and are quite simply out of good options to shelter migrants.”

Why youth shelters?

The difference between landing a spot in a youth shelter and winding up in a shelter for adults can be enormous.

As well as access to school enrollment and mental health services, youth programs offer direct access to legal assistance. People under 21 may be eligible for a Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) visa, a faster track to immigration status than joining the asylum backlog.

For 18-year-old Mamadou S., the chance to apply for a SIJ visa is one of the reasons he’s hoping to get into a youth center. “I don’t have the means for a lawyer,” he said.

Right now, he’s staying in one of the city-run tents outside of the Creedmoor Psychiatric Hospital in Queens, along with hundreds of migrant men. “In the youth centers, they treat you better,” he said.

Thierno Sadio Diallo is one of the lucky ones. After visiting Afrikana for help, the 18-year-old from Guinea found a bed at a DYCD-funded living facility in Brooklyn. He attends a GED program, and has his own room.

Adult shelters now limit stays for migrants to 30 days, after which some find themselves on the streets. But crisis shelters for young adults allow stays up to 90 days while they wait for a longer-term placement. Transitional independent living facilities, like the one Thierno is living in, allow residents to stay for up to two years as they look for a more permanent place, and help them in this search.

“For me, it’s very nice. I’m making friends. They don’t tell me I have to leave,” he said.

The demand for beds is highest among straight-identifying young men, but Kate Barnhart, who runs New Alternatives for NYC, a drop-in center for LGBTQ youth in Manhattan, has also seen an increase in LGBTQ young people being turned away from youth shelters.

Many of those who come to her seeking help are from countries like Turkey or Saudi Arabia, where it is difficult or even illegal to be gay. For them, getting access to a specialized shelter is especially crucial, as young adults placed in an adult shelter can sometimes face the same discriminatory behavior that caused them to flee.

“I don’t get a sense that they [the city] are thinking about young people or LGBT people at all,” said Barnhart. “My sense is that folks are still just overwhelmed by the volume of people and that they’re just thinking about, where do we put all these people?”

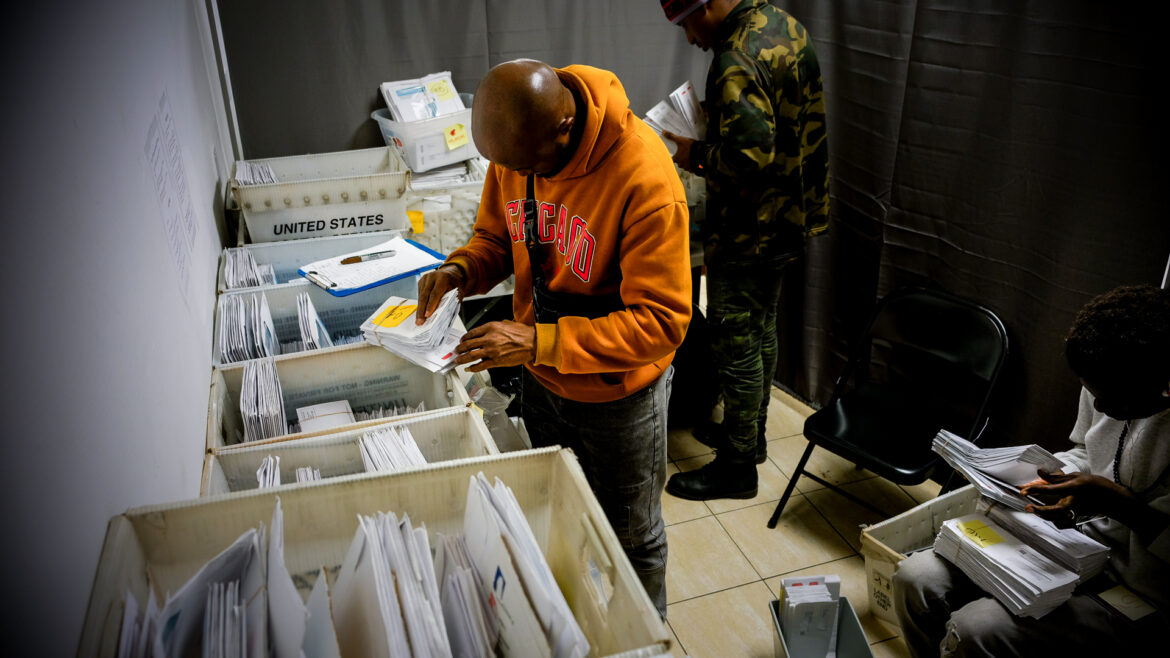

Adi Talwar

Volunteers sorting mail at Afrikana, a community center in East Harlem. Afrikana provides an address for unhoused immigrants to receive mail.‘A state of crisis’

A series of federal and state laws in the 1970s first established the legal framework for youth shelter sites, but it was a youth homelessness crisis 10 years ago that led to the settlement that underpins city services for homeless youth today.

In 2013, 11 young people sued the city, claiming that they were being denied housing in the city’s youth shelters. At the time, the city had only 253 such beds; data from the same period showed that on any given night, 3,800 youth were sleeping on the streets. The complaint filed by The Legal Aid Society described a homeless youth crisis, in which hundreds of young people were on waitlists for DYCD beds.

It took over six years of litigation before the city and Legal Aid agreed to a settlement, under which the city is obligated to publicize youth services to all homeless youth, regardless of immigration status. While it does not guarantee a youth-specific shelter bed to those aged 18 to 20, it does require the city to continually assess the number of beds available in the system, and to add more if it is determined that there aren’t enough.

But the legal threshold of “not enough” is nearly impossible to reach.

Under the terms of the settlement, the city must release Shelter Access Reports every six months showing how many people are on the waitlist. The plaintiffs can seek legal remedy only after 50 people have been marked as turned away over two successive six-month periods. In its report from the first half of this year, DYCD noted only seven youths were not able to be placed.

Powlovich thinks that’s “absolutely” an undercount. Before a turned-away youth is counted in the DYCD system, a provider must fill out extensive forms and send them to DYCD headquarters. When advocates call around to shelters and fail to find a spot, that’s rarely recorded in official form.

Meanwhile, DYCD does not maintain a waitlist. The department says the information they are required to keep on turned-away youth is minimal, and that they are in compliance with the settlement.

The arrival of hundreds of needy youth to the city has only exacerbated the crisis Legal Aid described in its original complaint.

“The youth-specific shelter system has been consistently underfunded for years,” said Judith Goldiner, attorney-in-charge of Legal Aid’s Civil Practice Law Reform Unit. “And despite significant legislative and programmatic advances over the past decade, the Legal Aid Society believes this system has been and remains in a state of crisis that screams for expanded support.”

Mamadou, the 19 year old from Guinea, now comes to Afrikana in Harlem every day, to check and see if a bed has opened in a youth shelter. When he hears that one hasn’t, he sticks around to help new migrants apply for IDNYC and get MetroCards.

“Each day when I come, if there’s still no room, I’ll help them out,” he said. “I’ll come back every day to see if there’s room.”

To reach the editor behind this story, contact Emma@citylimits.org.