A 2019 plan to expand the Justice Involved Supportive Housing program would satisfy a commitment in former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s Points of Agreement to close the city’s notorious jail on Rikers Island. The existing operators aren’t biting.

Adi Talwar

David Owens, 56, moved into his own apartment in 2021 through the city’s Justice Involved Supportive Housing program, following what he described as a “vicious cycle” of homelessness and incarceration.David Owens likes to talk about his goals for the future. Long term ones, like becoming a licensed clinical social worker, and short term ones, like riding a bicycle and playing handball to get his endorphins going.

Originally from the Bronx, the 56-year-old left prison in October 2020. Prior to that three-year stint, he recalls a “vicious cycle” of sleeping in parks and on subway cars, trying to get money to support his drug use, and being arrested as a result. But in March 2021, he moved into an apartment in his home borough—his first in decades.

Having an apartment is extremely important, Owens explained in July, at the Queens offices of The Fortune Society, the nonprofit that placed him: “For the person to get rest, make plans for the next day.”

Owens is among a small number of New Yorkers to receive a low-cost apartment through a niche program called Justice Involved Supportive Housing, or JISH. Launched in the fall of 2015, it is specifically for people with behavioral health needs who have the city’s highest rates of jail time and shelter stays.

Supportive housing is generally geared to tenants who have experienced homelessness, and have a mental illness or substance use disorder. Through JISH, tenants are matched with a case manager who serves as a point person for other services like substance use treatment, job training and public benefits, like food stamps.

That kind of support, advocates say, is needed to reduce both incarceration and homelessness. But a plan to expand JISH to 500 units from an initial 120—that would satisfy a commitment in former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s Points of Agreement to close the city’s notorious jail on Rikers Island—has barely advanced, despite a $93.7 million 2019 Request for Proposals (RFP).

At a public contract hearing on Oct. 26, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) announced its first award out of seven total applications: $10.69 million over nine years for 24 units, defined as studios, one-bedrooms, or half of a two-bedroom. The provider, Project Renewal, declined to comment.

Meanwhile, the three nonprofits managing JISH’s existing apartments—The Fortune Society, contracted to house 60 people, and Urban Pathways and CAMBA, to house 30 each—have declined to bid on the latest RFP. They say that the funding is inadequate, that the process for identifying tenants is a blunt instrument, and that the city is wasting money on both jail and shelter as a result.

New York City’s average daily jail population has increased from a recent low of about 4,900 in 2021 to over 6,000 people, more than half of whom have at least one symptom of mental illness. As of May, more than 1,200 people on Rikers had a serious mental illness, such as a psychotic, bipolar, depressive or post-traumatic disorder.

And many exit jail right into the shelter system, which is currently bursting at the seams. At any given time this year so far, there were about 1,900 people in Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelters either released from jail or on parole.

“We’d like to work with the city to craft a program that works for the individuals who are stuck in this cycle of homelessness and incarceration,” said Mark Hurwitz, chief operating officer of Urban Pathways.

Funding fight

The JISH approach has precedent. In the aughts, then Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s corrections and homeless services agencies generated a list of repeat jail and shelter users for a program called Frequent Users Systems Engagement, or FUSE. As with JISH, tenants got supportive housing operated by nonprofits.

A 2023 study by Columbia University researchers in conjunction with the Corporation for Supportive Housing (CSH), a nonprofit lender and industry advocate, checked in on 68 FUSE tenants 10 years after they were placed in supportive housing. Of the total, 63 percent saw no prison, jail or shelter time aside from limited shelter stays in the first months post-placement, versus 37 percent in a comparison group.

Martin Horn, professor emeritus at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, was Department of Correction (DOC) commissioner when FUSE launched, and championed it. “What was clear to me was the most important thing I could do to help keep the jail safe was to reduce the number of people in jail,” he said.

He also praised the cost savings. New York City spends more than half a million dollars per incarcerated person per year, according to CSH, based on a daily cost estimate by Comptroller Brad Lander and reporting on the average annual length of stay.

In some ways, today’s JISH model is simpler than FUSE. Ryan Moser, who helped implement the latter as a program manager at CSH, recalled a confusing web of funding sources, some of which came with strict eligibility requirements. But while JISH funding is streamlined, providers that operate the existing apartments say it’s too low.

The 2019 RFP, like their initial contracts, offers $10,000 in annual services funding per person, plus rent money, for providers who opt for a scattered-site model, renting apartments and subletting them to their tenants. A congregate option—tenants grouped together in one building with on-site services—offers $17,500 per person.

The higher funding for congregate is intended to cover building security, according to DOHMH. The same funding levels apply to NYC 15/15, another de Blasio-era program announced in 2015 to create 15,000 units of supportive housing for homeless adults with a serious mental illness or substance use disorder.

But providers say the JISH population needs extra support. Expectations for staff range widely, from helping tenants navigate court dates, to encouraging safe drug use and teaching independent living skills like cooking. The program also requires frequent in-person check-ins, especially in the first six months.

In 2022, CSH recommended $20,669 in service funding for each scattered-site JISH tenant, and $25,596 for congregate tenants, equivalent to funding for young adults in NYC 15/15. This could allow for low staff-to-tenant ratios, they say, and, for a scattered-site tenant, would cost less than 10 percent of the annual jail stay estimate.

Neha Gautam/Urban Justice Center

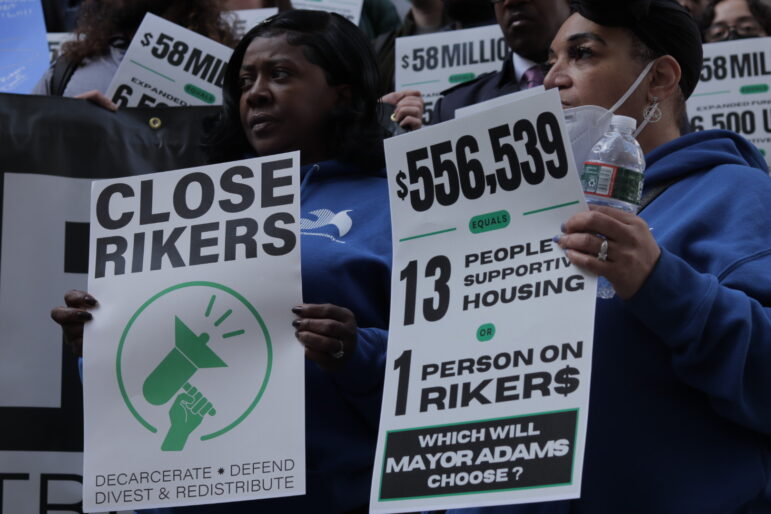

A May 2023 rally calling for the city to move forward with plans to close Rikers, citing the costs of incarceration compared to supportive housing.All of the existing JISH apartments are scattered—the congregate option was introduced in 2019—so many provider complaints are specific to that model, like the need for case managers to travel long distances between apartments.

CAMBA, for example, is headquartered in Brooklyn, but all of its JISH apartments are in the Bronx. Between the travel time, low salaries, and difficulty making contact with tenants, staff have resigned, according to Angeles Delgado, senior vice president of HIV/AIDS housing and health services.

“We have all these requirements that we’re asking, ‘Go chase them,’ even if you know that you’re going to get there, spending two hours on the subway, and not find them,” she said.

City Limits also heard complaints about the scattered-site model in general—high rents, and tenants falling behind on their portion. “I don’t know anybody that’s been looking to expand their scattered-site portfolio… because all of those contracts are such a bad deal,” said an industry source, who requested anonymity to speak freely.

The congregate option is appealing in theory, according to JoAnne Page, CEO of Fortune Society, but new buildings require years of planning. Projects that cater to the JISH population can also be met with protest, like a plan to build 50 supportive apartments at an empty staff residence adjacent to Jacobi Hospital in the Bronx.

Mayor Eric Adams’ administration has taken some steps to sweeten existing JISH contracts, including by increasing funding for rent by over $760,000 for the initial 120 units. The aim was to help move tenants from shared apartments to one-bedrooms and studios, after providers warned roommate arrangements were leading to conflict.

Owens, the JISH tenant in the Bronx, was initially placed in a two-bedroom. “I don’t want to blame the roommate,” he said. “I unfortunately have a history of mental illness. I’m thinking that I’m maybe not compatible to live with any person.”

He requested a transfer, and eventually got an apartment of his own. But others haven’t been so lucky. According to Page, Fortune Society is now spending up to $15,000 per year on services for each scattered JISH tenant, supplementing the initial $10,000 with some of the extra rent money. The result is that fewer tenants can move to singles.

“In effect, we are taking from Peter to pay Paul and leaving both of them hungrier than we would wish,” she said by email.

Making connections

There are currently hundreds of supportive housing apartments in New York City set aside for people with justice system history, with a patchwork of funding sources. And though criminal background checks for prospective tenants are still legal, city guidance prohibits supportive housing providers from using them.

But JISH aims to fill a gap in this safety net. Qualifying tenants, described in program documents as having the “highest rate of jail and shelter usage,” are often excluded from other supportive housing programs that require a person to be chronically homeless, or unhoused for extended periods that a jail stay can interrupt.

CSH has estimated that 2,589 people held on Rikers over a one-year period could benefit from supportive housing, but 1,812 of them—about 70 percent—would be excluded because they are not chronically homeless.

The city’s process for identifying JISH tenants also stands out in its simplicity. Most people apply for supportive apartments through the city’s Coordinated Assessment and Placement System, or CAPS. They must fill out copious amounts of paperwork and sit for interviews—a process critics say can be overly subjective.

Whereas for JISH, the city generates a list of people who qualify and distributes their names to providers.

Page of Fortune Society drew parallels to Housing First, pioneered in New York City in 1992 by psychologist Sam Tsemberis. According to the model, people move directly from the street into an apartment, on the theory that they don’t need to prove their readiness to live independently. Services are robust but optional.

“The idea is [JISH] is an immediate, or almost-immediate, placement,” Page said. But in practice, she and her peer organizations haven’t been satisfied with how DOHMH manages JISH’s matching process.

According to the 2019 RFP, nonprofits get a name and a “referral source” from DOHMH, either a jail, shelter or street homeless outreach team. They are expected to contact that entity to learn about the person, and start their search within two days. If a person can’t be found in 30 days, or refuses services, their name goes back on the list.

Related Reading: ‘A Lot of False Hope’: City Data Show Ongoing Barriers To Supportive Housing

Back in the aughts, FUSE teams had regular access to Rikers Island and shelters. Moser, now vice president for strategy at CSH, recalls sharing names off his list with a warden. “They’d go and knock on people’s cells and say, ‘Hey, there’s a person here to talk about housing recruitment, do you want to come down and check it out?’” he said.

That type of coordination is lacking today, JISH providers said. Some people are never found. “We will not meet the clients until the day that they get released from Rikers,” said Delgado of CAMBA. “We’ll have to meet them at the location without knowing what they look like or anything, just put them in an apartment.”

This cuts out the possibility to assess prospective tenants, she added, some of whom “are not ready for this level of independent living.” Mike Erhard, executive vice president for Delgado’s team, ticked off issues they have had with scattered-site tenants—not only JISH tenants—like apartment damage and drug selling on the premises.

The 2019 RFP states that providers can make swaps if they don’t believe their mix of apartments is a good fit for someone—“a program who has been awarded scattered site units can recommend that an individual be referred to a congregate setting, and vice versa”—but that option is hypothetical for now.

Hurwitz of Urban Pathways said his organization would like to meet with prospective tenants on the JISH list, either in person or by video. That way, his team could introduce them to the program and “make sure that the type of services that we can provide are going to be sufficient to make sure that they stay housed, or at least to maximize the possibility.”

But requests for more face time raised some alarm bells for Rosa Jaffe, director of social work at the civil practice at Bronx Defenders. Jaffe helps people who are struggling to get into supportive housing—or facing eviction—thanks to their justice system history.

“To me the relationship building they are asking for is putting unnecessary barriers up that can lead to denying housing to a population that is very vulnerable,” she said.

Murky future

Owens, the JISH tenant, celebrated one year in his one-bedroom apartment this month. In September, he got certified as a peer recovery advocate, to help others with substance use disorders. He played a few handball games this summer, and rode his bike. “I usually try to be cautiously optimistic about things,” he said during a recent phone call.

Meanwhile, the future of JISH remains murky. It is not clear if Project Renewal’s 24 new JISH units—the first trickle since the 2019 RFP was released—will be scattered around the city or grouped together in one building.

A DOHMH spokesperson did not address JISH directly in a statement, or complaints about funding and structure, but said that the department’s goal is to “reduce barriers to access [housing], including for people returning to our communities from jails.”

Horn, the former DOC commissioner, urged the Adams administration to work with the existing JISH contractors and embrace their advice to improve the program. “We saw the providers as partners in solving our problem,” he said. “And that’s how they need to be seen today—not as contractors with their hands out.”

Reflecting on his time traveling to shelters and Rikers Island to meet with prospective FUSE tenants, Moser of CSH said it was invaluable. Not only was he able to find people in the first place, but he could build trust with them over time.

“I don’t think I ever talked to a FUSE person that I was outreaching to, where I had a real conversation, where they had not been already promised housing at some point by somebody and it didn’t work out,” he recalled. “This is not people’s first rodeo. They have good, honest, distrust in systems and it needs to be respected.”

Ideally, he said, the city would give JISH providers the funding they are demanding, and work closely with them on some type of coordination with jails and shelters. Outreach teams should also check their assumptions, as he learned to, and place people in apartments as part of the mutual trust-building work.

“If the city leans in here, they could make this program run,” he added. “There’s not something about this group that is un-housable.”

To reach the editor behind this story, email jeanmarie@citylimits.org. To reach the reporter, email emma@citylimits.org.