The city’s education department insists the funding system is flexible, but the comptroller and education advocates worry some schools won’t get what they need if ‘massive numbers’ of new students enroll later in the year.

Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

A scene from the first day of school in September 2022.The comptroller is calling on the city’s education department, New York City Public Schools (NYCPS), to revamp its funding process to better prepare for incoming students throughout the school year, as asylum seekers continue finding home in New York City.

In a September report on school funding, City Comptroller Brad Lander pointed to potential issues in the city’s Fair Student Funding (FSF) formula, saying some schools “may struggle to serve an influx of new children” throughout the year, since the funding system is designed for most students to enroll by fall.

Municipal funding for schools is largely based on enrollment, and the final system-wide tally for the year is taken on Oct. 31. Since the last time a system-wide enrollment tally was taken in the fall of 2022, city schools have seen at least 22,700 new students living in temporary housing enroll, many of whom came to the city seeking asylum, according to NYCPS. About 11,000 students in temporary housing have enrolled since July 2023, according to Nicole Brownstein, the director of media relations.

In an email, Nathaniel Styer, a spokesperson for NYCPS, disputed that the Oct. 31 date is “some sort of cut off,” saying the city “will continue to provide funding to schools as they enroll students.”

In addition to enrollment data taken on Oct. 31, school budgets are determined by conversations and appeals between NYCPS’ central office, district superintendents and principals. Those conversations continue throughout the school year and are handled on a case-by-case basis, according to NYCPS. Project Open Arms—the city’s “comprehensive support plan” for asylum seekers—notes that the city will “consistently monitor school registers through the October 31 snapshot date” and release funds if needed.

“We will continue to respond, financially, to schools’ needs throughout the year,” Styer said. “We will continue to provide funding to schools as they enroll students.”

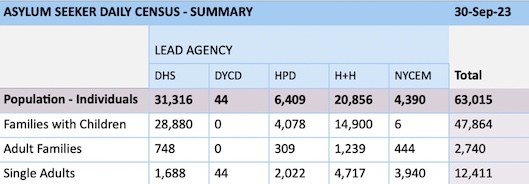

But the comptroller’s office does not think the case-by-case system is sufficient “when massive numbers of students are showing up after October 31.” Immigrants have continued to come to New York in recent months—an average of 600 a day in mid-October, officials said—and families with children currently make up the majority of those staying in the city’s shelter system.

NYC Mayor’s Office

Numbers from City Hall on asylum seekers in the city’s shelter system, broken down by administering agencies, as of Sept. 30, 2023.Criticism of NYCPS’ ability to serve expected incoming students comes after the DOE announced that for the first time in four years, schools with enrollment declines as of Oct. 31 will have their budgets cut midway through the year.

Additionally, Mayor Eric Adams announced a policy earlier this month that will force recently-arrived immigrant families living in shelters to reapply and potentially change locations every 60 days—something advocates say may be extremely disruptive for students’ educations.

While Adams has claimed that “no child is going to have their education interrupted,” the policy may cause further shifts in enrollment, as some families may seek out schools closer to their new shelters. In addition to their housing status, many new immigrant students have “tremendous” needs that require more resources and funding to support, according to the comptroller, including learning English as a second language and having suffered trauma.

“[NYCPS] must ensure that those schools are adequately funded—throughout the school year—as these numbers continue to rise outside of the strict timelines used for adjusting FSF allocations,” the comptroller wrote.

Lander’s office said it is difficult to track if schools serving the 22,700 students who enrolled after last October have received sufficient funding. Initial budgets for the current school year were based on enrollment from Oct. 31, 2022, plus adjustments made on a case-by-case basis for enrollment trends and new students enrolled after, according to NYCPS.

Similar budget adjustments will be made this year. For example, if a school receives 15 new students after Oct. 31, they should appeal, and may receive funds to hire an additional teacher, according to NYCPS.

But advocates said that last year, schools had to wait too long for their budget appeals to be granted, while many continued to accept new students.

Naveed Hasan, a parent representative for Manhattan on NYC’s Panel for Educational Policy (PEP), the city’s school board, said the appeal process can be stressful for schools and creates a feeling of “austerity,” forcing principals to make fiscally conservative decisions.

“Why even put schools through that pain given that you know that students are enrolled?” Hasan said. “The budget cycle in [NYCPS] is very poorly suited toward having thousands of new students coming every month. And the issue with trying to address this based on a case-by-case basis is that there are hundreds of schools that are impacted.”

During September’s PEP meeting, Lara Lai, a policy analyst for Lander, called for systemic change to the funding formula. “This is clearly a system that was not designed to capture large numbers of students enrolling later in the year,” Lai said.

But creating a new, automated system for adjusting budgets based on enrollment changes throughout the year would be “financially impossible,” according to NYCPS.

Styer, the education department’s press secretary, said NYCPS is working to ensure schools have what they need to serve new students, “from funding to staffing.”

“We know this is a constantly changing situation and we are making sure our response is flexible and meets the needs of our schools—no matter the time of year,” Styer said.

Funding uncertainty

At minimum, all schools this year were allocated the same funding they received in their initial budget last year, according to the comptroller, and some schools even received more. But those initial budgets from last year were a “low bar to start with,” according to Lander.

Additionally, NYCPS announced last week that for the first time in four years, schools with enrollment declines will have their budgets cut midway through the year, during what’s known as the mid-year adjustment. Schools that have lower enrollment when tallies are taken on Oct. 31 will have their budgets cut in the middle of the year. Those with increases will have funds added.

City schools have lost over 120,000 students in the last five years, according to NYCPS. But there is concern that schools with declining enrollment, which will be required to return funding to NYCPS because of it, could see an uptick in enrollment later in the year. They would then need to appeal their budget allocation and request additional funding.

“We will continue to provide funding to schools as they enroll students,” said Styer, the NYCPS spokesperson.

But Paullette Healy, a board member of an independent parent organization called the Education Council Consortium, fears that the appeals process will be time consuming and may leave schools without adequate funding until late into the school year, assuming their appeals are eventually granted.

Hasan agreed, saying funding delays may cause learning “disruption.”

“It’ll be counterproductive to the actual schools and students that need these trauma-informed and urgent services in the beginning of their time in New York City, to stabilize their situation so that both they can learn and the other kids in the class are also able to learn without any disruption,” Hasan said.

Despite NYCPS’ promises to meet schools’ needs throughout the year, Hasan is also skeptical schools will actually receive what they “deserve.”

“[NYCPS] says you can always raise your hand and say ‘Look, we’re having issues and we need money.’ But we’re also in a climate where the city is saying it is a fiscal disaster,” Hasan said. “I wonder how easy it is for a school to say ‘Hey, I need 100,000 extra dollars; I need these two staff members,’ without it being in some sort of awkward situation.”

Hasan said “standard policies” for enrollment adjustment are “more helpful” because they put less pressure on schools to “constantly be begging.”

Staffing concerns

Lander wrote in his September report that NYCPS “should carefully monitor the placement of children of families seeking asylum, and where possible, help schools with reduced enrollment reach their capacity.”

Students are generally placed in schools based on seat availability and travel distance from where their family is living, according to NYCPS. Many schools where the city has identified availability have seen declining enrollment in recent years, officials say.

But incoming students are still being concentrated in certain schools and districts, causing some to be overwhelmed, advocates say. Healy said that of the city’s 32 geographically bound school districts, five are receiving an overwhelming share of new students: District 2 in Manhattan, Districts 24 and 28 in Queens, and Districts 9 and 10 in the Bronx.

Within those five districts, 33 schools are receiving a disproportionately high share of new students, according to Healy.

This is largely because incoming students living in shelters have the right to attend a school in their neighborhood. Under the national McKinney-Vento Act and NYCPS’s Chancellor’s Regulations, a student in temporary housing has the right to “stay in their current school or choose to attend a zoned school.”

Additionally, many incoming students require schools with teachers who speak their first language or can offer other specialized services, which can be rare.

Nevertheless, Healy said, there are 180 schools she knows about around the city that are experiencing enrollment declines and would be “primed and ready to take on these students,” but aren’t getting many.

“Right now, the only method of enrollment for these students is if the shelter happens to have a Students in Temporary Housing liaison,” Healy said.

Healy said there is a lack of interagency coordination, as well as staffing shortages, leading to over-enrollment at some schools instead of a more even distribution of students across the city.

In order to place students in schools with seats that are close to their residence, Project Open Arms facilitates two meetings a week with NYCPS’ Enrollment and Students in Temporary Housing offices, superintendents, the Office of Pupil Transportation and the Division of Human Resources.

Healy said it was concerning that there are vacancies throughout the office of Students in Temporary Housing, including the role of “Director of Regional Support.” After City Limits inquired about the vacancy, NYCPS took down a job listing for it, and was not able to provide an update on the hiring process in time for publication.

Since the NYCPS hired 100 shelter-based coordinators last year, “only a few” vacancies have occurred and they are trying to fill them quickly, according to NYCPS.

But Healy always thought 100 shelter-based staff was too few to begin with. City Council members initially called on NYCPS to hire 150. But the agency said it does not intend to create new, full-time positions, just fill vacancies.

Jennifer Pringle, a representative from Advocates for Children of New York, said she wants NYCPS to increase funds for shelter-based staff.

“I can’t emphasize how critical those positions are to making sure that families connect with school and connect with the services that they need in school,” Pringle said.

To reach the editor behind this story, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org