Desperate to find work, many immigrants pay upfront fees to employment agencies, unaware that requiring payment before a job placement is prohibited.

Lea la versión en español aquí.

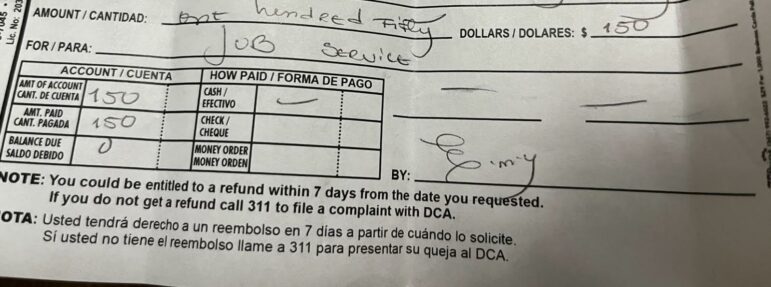

For two months, Jose saved as much as he could from odd jobs to stash away $150. It was enough to pay an employment agency for three chances to find a stable job in New York City, where he had arrived in July 2022 after crossing the U.S.-Mexico border.

“They ask about your work experience, English proficiency, whether you have a work permit, and whether you prefer cash or check payment,” explained Jose, who asked that his full name not be used for fear of jeopardizing his immigration case. “Depending on what you respond to, they place you.”

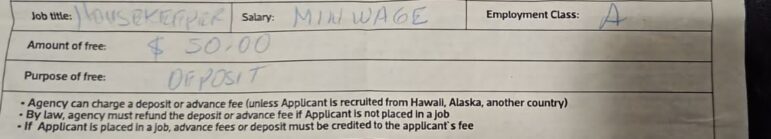

After paying $150 to Napoli Employment Agency in Jackson Heights, Queens, and receiving no contract or receipt, Jose was offered a gig cleaning restaurants in Flushing. It would pay $80 per place cleaned, he was told, with no specific check-in or check-out times.

Jose’s name, agreed payment, prospective employer’s name, and interview address were handwritten on a piece of cardboard, and with that he set off to a supermarket parking lot in Flushing. It was almost empty, he remembered, just a white van parked there, so he showed the piece of cardboard with the details to the driver, who told him to get in the van for the interview.

“It was an interview by Google translation,” Jose said, adding that he learned the pay would be less than he had been told—$70. He didn’t like that, and the employer didn’t like that he lived in a Brooklyn shelter. So both parties turned it down.

Jose returned to the agency that afternoon to try a second time. Both his second and third attempts did not result in a job, and he did not receive his deposit back. (Reached by phone, Napoli Employment Agency said they were too busy with clients to speak to a reporter.)

City Limits spoke to seven asylum seekers who said that they had paid employment agencies anywhere from $50 to more than $150 in the hopes of finding under-the-table work.

Not only did none of them find jobs, they were all charged before they were placed—a practice that the city’s Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP), which regulates and licenses employment agencies, says should not happen. Refunds were partial, or nonexistent.

Yet while these improper practices appear to be prevalent, DCWP is on track to receive fewer complaints about employment agencies this year than it did in 2022. Immigrants said fear of retaliation, combined with the desire to find a job quickly, can deter them from filing complaints, while advocates described a lack of adequate city enforcement to punish bad actors.

Perfect storm

Immigrants in New York City have long been vulnerable to labor scams. The Justice for Job Seekers campaign launched in 2014, raising awareness about improper fees, deceptive advertising, lack of contracts and sub-minimum-wage jobs, among other issues. A 2016 report from the state legislature emphasized that newly-arrived immigrants are particularly vulnerable.

But a recent wave of asylum seekers in New York City—more than 95,000 have arrived in New York since last year—are uniquely ripe for exploitation, experts and advocates say. They are a large, newly-arrived population, desperate to find jobs as quickly as possible and often unaware of regulations intended to protect consumers.

“This is the perfect storm for unscrupulous employers and unscrupulous employment agencies,” said Hildalyn Colon-Hernandez, deputy director at New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE), an advocacy group that says it has seen an uptick in complaints about fraudulent agencies. “We haven’t seen the tip of the iceberg,” she added.

For months, city officials, affected immigrants, and advocates have implored the federal government to expedite work authorization for asylum seekers, who aren’t eligible to work legally until they’ve had an active asylum application for at least six months.

“What is more anti-American than coming to this country and being told you can’t work?” Mayor Eric Adams said recently during a community event.

In the meantime, it is not uncommon for employment agencies to direct people to work that exists outside of the authorized job market, according to advocates who have seen for decades how the local economy is sustained by both formal and informal jobs.

Up-front charges

DCWP recently launched an outreach campaign, working with organizations like NICE and individual legal providers, to ensure that asylum seekers are aware of their rights and the consumer protections to which they are entitled.

“Our new outreach campaign [is] geared towards people seeking asylum because of this growing risk,” DCWP spokesperson Michael Lanza told City Limits.

As of June 30, there were 257 licensed employment agencies in New York City, including the agencies referenced in this story. These companies can help job seekers find work for a fee, but that fee is not supposed to be paid upfront—key information that some immigrants are unaware of. Moreover, according to DCWP, immigrants who have paid an advance fee have the right to a full refund.

“Employment agencies cannot charge a fee before they place you in a job. This includes paying fees upfront for the ‘chance’ to get a job,” Lanza explained.

But several immigrants reported the opposite experience: the employment agencies they sought work from charged first.

Jennifer, 39, who asked that her full name not be used for fear of jeopardizing her immigration case, was first sent to a job as a housekeeper, which required her to have read and studied the Guide for Housekeepers Working in Jewish Homes. It did not work out. According to Jennifer, she worked at one house for just two days. Golden Rose Employment Agency did not call her back with additional work and there was no refund.

In another case, Jeni, 34, was sent to a textile factory where she was required to speak English even though she had told CMP Employment Agency staff that she did not speak it. After the second attempt at a motel that was not even soliciting employees, Jeni knew she wanted her money back. But the agency told her she would have to go to another prospective job visit to get back just 60 percent of the $150 she had paid.

“I was told that they kept a part for administrative expenses,” Jeni said in Spanish.

“I was filled with rage, impotence, and I started to think: that is the way they steal—sometimes we are so naive, so big in age but naive out of necessity,” she added.

CMP Employment Agency did not answer multiple calls seeking comment. On one occasion, an employee answered, but hung up after a reporter identified themselves. Reached by phone, a Golden Rose Employment Agency staffer said that since the city started receiving a larger number of immigrants last year, there are more workers than jobs and the agency must collect fees first because otherwise workers do not pay.

“New York is maxed-out,” she said.

Incomplete Receipts

According to the state’s Employment Agency Law, which the city enforces, the receipts that agencies issue must include language in bold capital letters stating that “an employment agency may not charge you, the job applicant, a fee before referring you to a job that you accept.”

And, that, “If you pay a fee before accepting a job or pay a fee that otherwise violates the law, you may demand a refund, which shall be repaid within seven days.”

Of the receipts reviewed by City Limits, none included all of the required information, which is also laid out in sample receipts produced by DCWP. One stated that agencies must refund the “deposit” or “advance fee” if the applicant is not placed in a job, though the job seeker couldn’t understand it because it was printed in English.

Fear of retaliation

Job seekers who think their consumer rights may have been violated can file a complaint with DCWP online, or by calling 311. Complainants do not have to give their name or immigration status.

According to DCWP figures, the number of complaints filed against employment agencies appear to be on the decline since the city began welcoming more new immigrants last year.

In addition to improper fees, complaints may allege that agencies placed people in jobs that paid below minimum wage, or offered fake Social Security numbers or Green Cards.

Last year, DCWP received 130 complaints about employment agencies, conducted 81 inspections, and issued 22 summonses. But this year’s numbers are on track to be lower: there were 40 complaints filed between January and June, and 17 inspections conducted. Only two summons have been issued so far this year.

As with many issues affecting immigrant communities, the available figures do not reflect the true scope of the problem, which experts say is likely due to underreporting. Some of the immigrants City Limits spoke with believed that by filing a complaint, they would be creating trouble and might face retaliation, when all they want is to find work.

In a statement to City Limits, a spokesperson for the New York State Department of Labor said that the office also does not collect data on asylum status, in the hopes that undocumented workers will feel comfortable coming forward.

“Due to the hurdles caused by fear of being prosecuted over documentation status, many undocumented workers do not come forward with complaints,” the spokesperson said. This “makes it difficult to obtain any data on hiring for those with asylum status,” they added.

Most of the immigrants City Limits interviewed said they did not know that they had the same rights as anyone else to complain about employment agency practices.

Enforcement challenges

Even if a wronged job-seeker does file a complaint, advocates lament what they describe as a lack of enforcement. “Employment agencies have no accountability,” said Kazi Fouzia, director of organizing for Desis Rising Up & Moving (DRUM).

Once a complaint is made to DCWP, the agency is supposed to investigate and take action. Responding to complaints is the primary way the city finds out about illegal activity, according to DCPW. Once a summons—commonly called a “ticket”—is issued, violators can be subject to fines issued by the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings (OATH).

Yet the number of inspections performed by DCWP has declined from a 2019 peak, as has the number of summonses issued. According to the city, the COVID-19 pandemic made performing inspections more challenging.

“Since the proliferation of remote work at the outset of the pandemic, DCWP has faced challenges when attempting to inspect employment agencies as the offices will claim to be closed… when we arrive, or staff are not present on site,” Lanza said. “In 2022, DCWP was only granted entry to complete inspections in approximately 22 percent of instances.”

In the case of Jose, the asylum seeker who sought work through Napoli Employment Agency, the prerequisite complaint never materialized.

After his failed job interview in Flushing, he was sent to a warehouse in Queens where he packed orders from 9 am to 6 pm. At the end of the day, the employer told him that it had been a test day, and there would be no pay—an apparent instance of illegal wage theft.

Jose then went back to the agency to complain. He said that staff reassured him, saying that he had a third chance: as a busboy. But when Jose arrived at the restaurant, he learned that the job required intermediate English, which he did not have.

Rather than return to the agency or pursue a formal complaint with the city, Jose decided to continue his work search elsewhere.

“That's when I gave up, at that moment,” Jose said. “I didn't go to the agency anymore. I thought it was disrespectful. They take advantage of the people who are arriving.”

2 thoughts on “The High Cost of the NYC Job Hunt for Asylum Seekers ”

Is there a Spanish-language version of this article? Would like to share with our migrant contacts.

Yes! https://citylimits.org/2023/08/10/el-alto-costo-de-buscar-empleo-en-la-ciudad-de-nueva-york-para-los-solicitantes-de-asilo/