In an unusual twist, the two tenant-aligned members of the Rent Guidelines Board, tenant lawyer Adán Soltren and organizer Genesis Aquino, voted in favor of Wednesday’s increases—3 percent for a one-year lease and a split two-year lease of 2.75 percent in year one and a further 3.2 percent in year two.

Adi Talwar

The Rent Guidelines Board held its final vote Wednesday night at Hunter College.Tenants across nearly 1 million stabilized apartments in New York City are facing further rent increases starting later this year, though shy of those instated in 2022, following a raucous vote in Upper Manhattan Wednesday night.

The nine-member Rent Guidelines Board, made up of mayoral appointees, voted 5-4 in favor of rent hikes of 3 percent for a one-year lease and a split two-year lease: 2.75 percent in year one and a further 3.2 percent on top of that amount in year two, equivalent to a fixed two-year increase of about 4.4 percent.

The adjustments will apply to leases signed starting Oct. 1. Last year, the first vote under Mayor Eric Adams, saw the highest rent increases since 2013—3.25 percent for one-year leases and 5 percent for two-years. By contrast, former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s terms saw the only rent freezes in the board’s history, in 2015, 2016 and 2020.

Melissa Bosley, a rent stabilized tenant from Soundview in the Bronx, explained Wednesday that she usually picks a two-year lease, but opted for a one-year lease in 2022 because 5 percent was too high for her.

“I can’t afford my rent, to be honest,” she told City Limits at Hunter College waiting for the vote to start. “I’m actually a full-time student right now, so I’ve been kind of struggling trying to get help for the rent. And so knowing the rent is going to increase, and knowing that right now I can’t even afford it, that’s a very scary reality to face.”

The Rent Guidelines Board, or RGB, was formed in the late 1960s to regulate a subset of city apartments in response to falling vacancy rates and rising rents. In addition to limited annual rent adjustments, stabilized tenants generally have the right to a lease renewal, which can help them organize for building repairs.

A preliminary board vote took place in May, setting ranges for this year’s increases. It was hosted at Cooper Union, and saw numerous tenants and progressive City Council members rush the stage, interrupting proceedings.

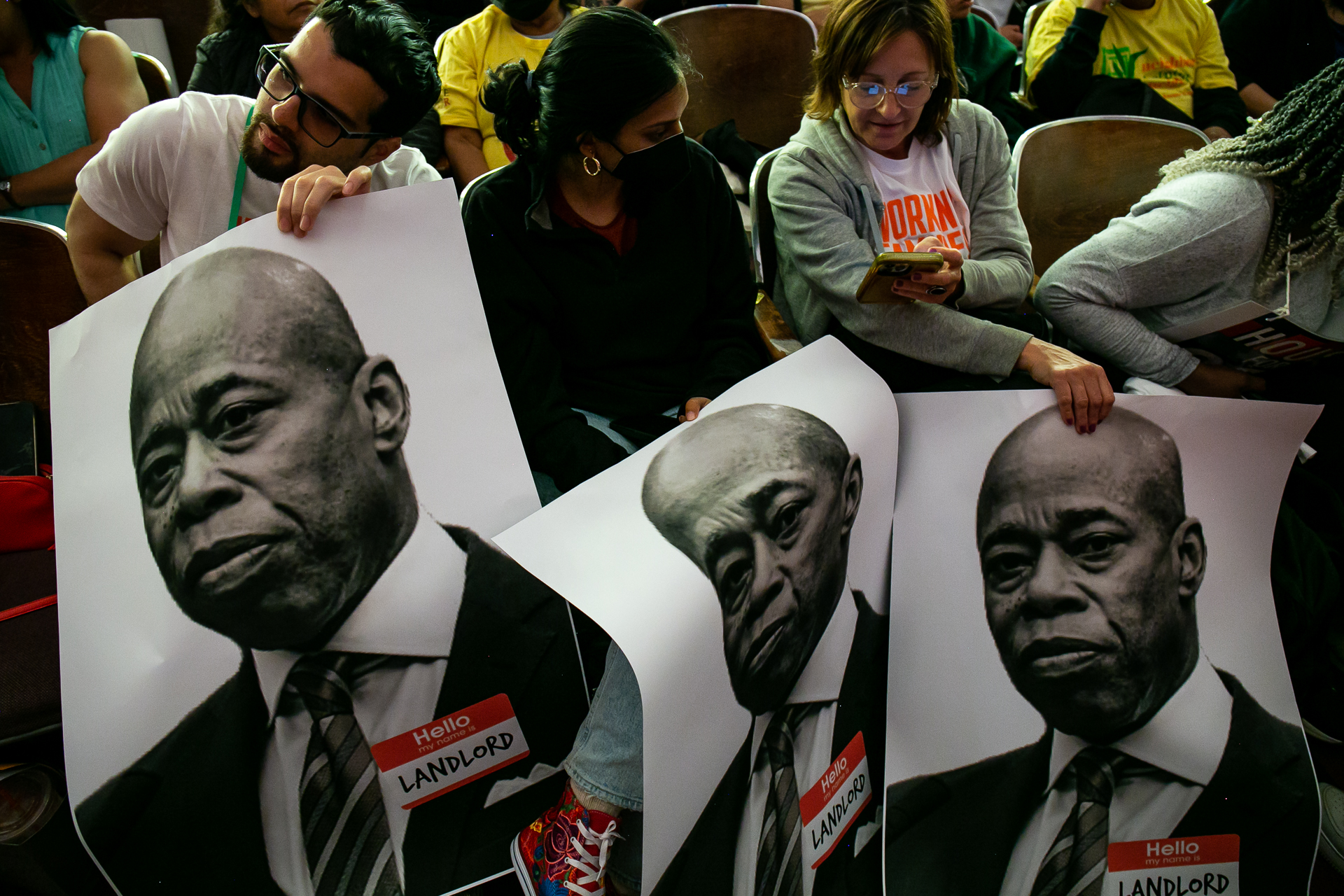

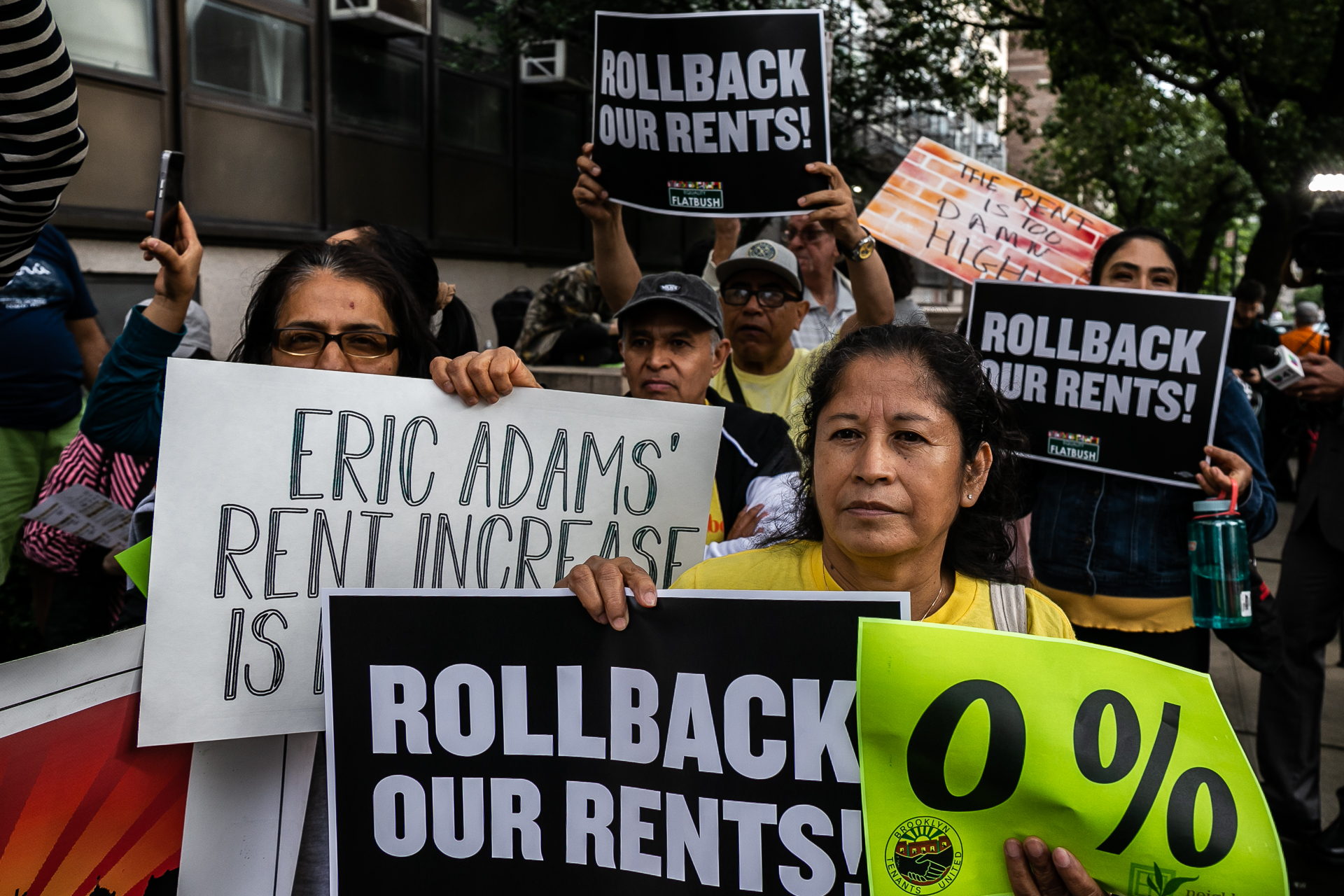

The scene at Hunter College was more regulated Wednesday, with ample security and caution-tape blocking off the first several rows of the auditorium. Yet tenants brought whistles—despite a formal ban on noisemakers—and chanted throughout the meeting: “Rent rollback!” and “Shame! Shame! Shame!”

Scenes from the Rent Guidelines Board meeting Thursday night.

Scenes from the Rent Guidelines Board meeting Thursday night.

Scenes from the Rent Guidelines Board meeting Thursday night.

Scenes from the Rent Guidelines Board meeting Thursday night.

Scenes from the Rent Guidelines Board meeting Thursday night.

Scenes from the Rent Guidelines Board meeting Thursday night.

Prior to its final vote each year, the board holds several public hearings and reviews a series of reports produced by its staff, aimed at assessing the economic conditions tenants and landlords are facing.

This year’s analysis saw a year-over-year increase in landlord operating costs, based on a basket of typical expenses including taxes, utilities and insurance. Taxes, which are weighted most heavily, grew 7.7 percent over the year ending in March. Operating costs overall grew 8.1 percent, nearly double last year’s growth.

But tenant advocates urge a longer view of landlords’ economic conditions, pointing to a separate RGB finding that inflation-adjusted net operating income has grown almost 50 percent since 1990.

Meanwhile, record inflation in the New York City metropolitan area in 2022—6.1 percent, the highest since 1981—wiped out any wage gains for tenants, according to RGB findings.

Board Chair Nestor Davidson published a lengthy statement following Wednesday’s vote, saying that he sought a balance, “considering both current conditions and long-term trends.”

In an unusual twist, the two tenant-aligned members of the Rent Guidelines Board, tenant lawyer Adán Soltren and organizer Genesis Aquino, voted in favor of Wednesday’s increases.

The four “no” votes came from the two landlord-aligned members, who argued for a larger increase—Christina Smyth and Robert Ehrlich—plus two of the five public members, Doug Apple and Arpit Gupta.

Typically, the tenant and landlord members deflect, and adjustments pass 5-4 thanks to “yes” votes from the public members, including the chair. Last year was also unusual, in that former public member Christian González-Rivera voted against the chosen percentages, and landlord member Smyth voted for them to round out the majority.

Speaking to City Limits following Wednesday’s vote, Soltren said he and Aquino feared an even higher increase if they didn’t join up with some of the public members, due to a division within their ranks. The two-year split lease would “lessen the blow” with a smaller percentage in year one, he added.

“Palatable is not the right word because this is very much not palatable for anyone on my side of the aisle, but we agreed to it with the caveat that it had to be broken up so people are not getting slammed with it all at once,” he said.

Michael Tobman, director of communications and membership for the Rent Stabilization Association, a landlord trade group, described the split lease as ridiculous and said it was indicative of a broken system.

“Apparently you need to have an advanced degree in calculus to figure out what the Rent Guidelines Board built consensus around this evening to pass a proposal, in a broken system that is not data driven, and is not policy driven,” he told City Limits.

Esteban Girón, an organizer with the Crown Heights Tenant Union, agreed that the math is complicated. “Nobody’s going to understand it,” he said. “I barely understand it.”

He did not fault the tenant members—“there were no good options”—but expressed concern that the vote would queue up a victory lap for Mayor Adams, who has appointed six of the sitting members of the board since taking office.

Indeed, the mayor commended Wednesday’s vote in a statement. “Finding the right balance is never easy, but I believe the board has done so this year — as evidenced by affirmative votes from both tenant and public representatives,” he said.

But standing outside of Hunter College following the vote, Aquino, the only rent stabilized renter on the board, said that the vote was not her preference, and that she had been put “between a wall and a hard place.”

“A lot of the people who came to testify will continue to struggle even more, and I think this vote is going to push them toward displacement, because they cannot afford what they are paying right now,” Aquino added.

She went on to criticize the board as too opaque. “I think that the process should be more transparent,” she said. “We should have more meetings and more data, and maybe have negotiations in a regular meeting so people can see the process and see what’s what. And I think that would make it more democratic.”