The Rent Guidelines Board Tuesday voted in favor of rent hikes between 2 to 5 percent for a one-year lease and 4 to 7 percent for two-year leases. A final vote won’t happen until June, but the preliminary numbers have historically set the goalposts: annual adjustments have fallen within these ranges since 2004, when the board began using them.

Tenants across nearly 1 million stabilized apartments could be facing rent increases on par with or greater than last year, following a raucous meeting Tuesday night held by the New York City Rent Guidelines Board.

The nine-member board, made up of mayoral appointees, voted 5-4 in favor of rent hikes between 2 to 5 percent for a one-year lease and 4 to 7 percent for two-year leases. The last time rent-stabilized tenants consistently faced increases in this range was in the mid-aughts up through 2013, under Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

“I’m still trying to dig myself out from debt I got during the pandemic. I was hoping that some student debt was going to be canceled. Everybody I know is living in precarity,” said Crown Heights tenant Sarah Lazur. “For most people I know, this basically wipes out any raise that they got, any cost-of-living increase they got at their job.”

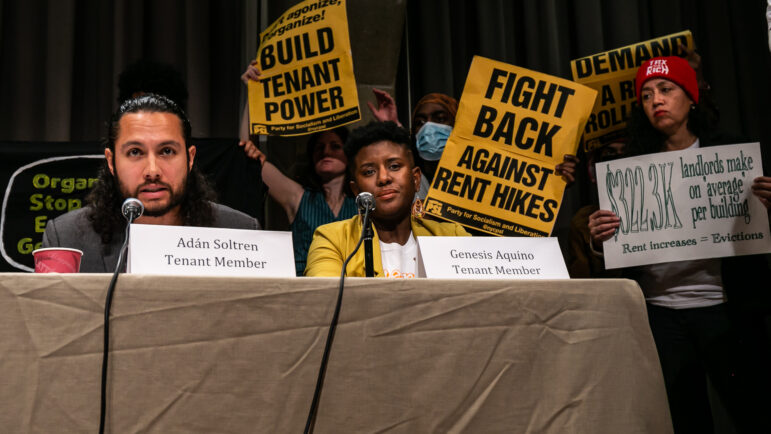

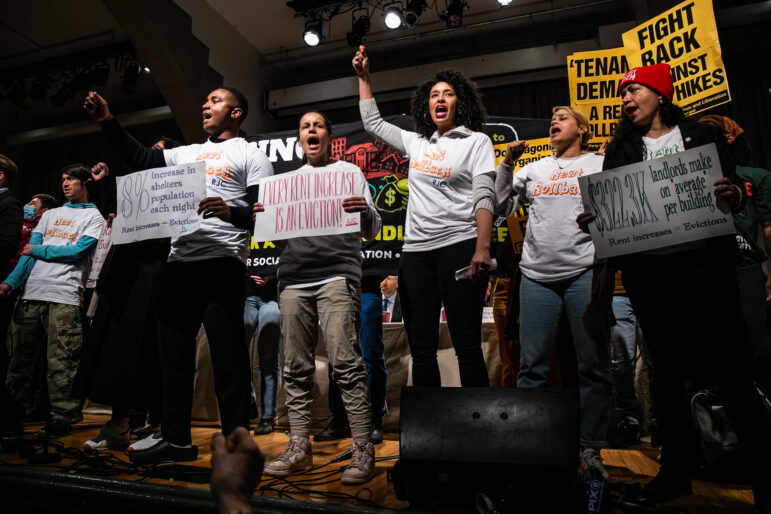

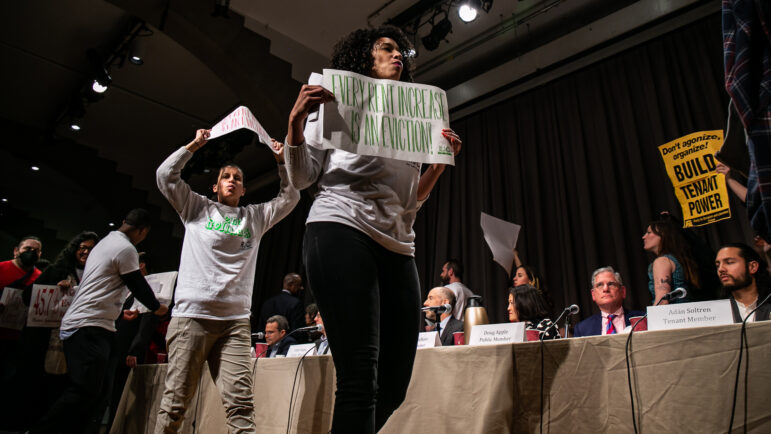

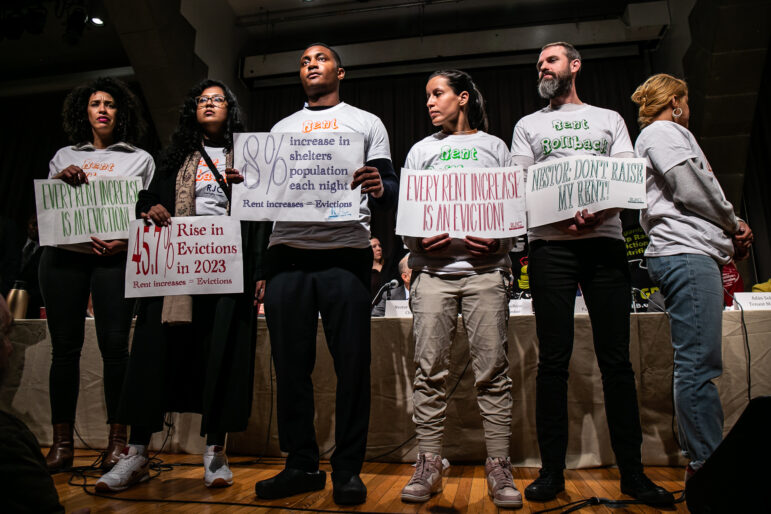

Before the vote could be cast inside Great Hall at Cooper Union in Manhattan—the first under newly-minted board chair, Fordham Law professor Nestor Davidson—tenants in the audience managed to drown out any order of business for more than an hour, stomping, whistling, banging chairs, and chanting “Shame!” and “Rent rollback!”

A group of City Council members and tenants then rushed the stage, prompting the board to retreat. When members returned to their seats, tenants proceeded to march around them in a tight circle.

Councilmembers Chi Osse, Tiffany Caban, Sandy Nurse and Alexa Aviles joined tenant activists who rushed the stage ahead of the Rent Guidelines Board vote.

Tenant activists and lawmakers rushed the stage ahead of the Rent Guidelines Board preliminary vote.

Councilmembers Tiffany Caban and Sandy Nurse circling the Board’s members during Tuesday’s protest.

Councilmembers Sandy Nurse, Shahana Hanif, Chi Osse and Tiffany Caban were among the protestors who rushed the stage ahead of Tuesday’s preliminary vote.

“The Rent Guidelines Board meetings every year are always a place of a lot of activity and actions and pushback,” said Brooklyn Council Member Sandy Nurse, who participated in the protest with several Progressive Caucus colleagues. “But I think it is important to escalate, because the level of pushback needs to match the scale of what’s happening.”

Tenants and landlords will be able to voice their opinions at hearings ahead of a final vote June 21, and the rates will apply to leases signed on or after Oct. 1. But Thursday’s preliminary vote has historically set the goalposts: Annual adjustments have fallen within these ranges since the board began using them in 2004.

Last year saw the city’s highest rent increases since 2013—3.25 percent for one-year leases and a 5 percent increase for two-year leases, plucked from preliminary ranges of 2 to 4 percent and 4 to 6 percent.

Ahead of tonight’s preliminary Rent Guidelines Board vote @ Cooper Union, here’s a helpful table I shared last year showing preliminary votes over time and where the final votes have landed. Historically, the prelim. has set the goalposts: pic.twitter.com/qTpltYPxzL

— Emma Whitford (@emma_a_whitford) May 2, 2023

By contrast, former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s terms saw the only one-year rent freezes in the board’s history, in 2015, 2016 and 2020. Unlike de Blasio, who was explicit in calling for freezes, Mayor Eric Adams had taken a more hands-off approach. “I don’t meddle,” he told state lawmakers in February. “I appoint, and I take a step back.”

But Adams changed tack Tuesday, stating that the board should consider a final vote below the high end of the adopted ranges and calling the 7 percent figure “clearly beyond what renters can afford and what I feel is appropriate this year.”

The Rent Guidelines Board, or RGB, was formed in the late 1960s to regulate a subset of city apartments in response to falling vacancy rates and rising rents. Prior to its annual vote, the board reviews a series of reports produced by its staff, aimed at assessing the economic conditions tenants and landlords are facing.

Adi Talwar

The nine-member Rent Guidelines Board, pictured here at Tuesday’s meeting, was formed in the late 1960s to regulate a subset of city apartments in response to falling vacancy rates and rising rents.Several metrics the board uses to assess landlord circumstances have worsened year-over-year. For example, one study calculates their net operating income, or NOI, which is revenue after operating expenses, albeit with a one-year lag. NOI fell 9.1 percent between 2020 and 2021, dragged down by sharp declines in Manhattan.

The board also calculates the cost of operating buildings with rent stabilized units, based on a basket of typical expenses including taxes, utilities and insurance. Taxes, which are weighted most heavily, grew 7.7 percent over the year ending in March. Operating costs overall grew 8.1 percent, nearly double last year’s growth.

“Decreased income is failing to meet ever-increasing costs in an unsteady economy,” said Michael Tobman, director of communications and membership for the Rent Stabilization Association, a landlord trade group, ahead of Tuesday’s meeting.

Ann Korchak, president of the group Small Property Owners of New York, owns two 10-unit brownstones in Manhattan with a mix of regulated and unregulated units. “What I was paying in property taxes in 2020 at the onset of the pandemic and what I’ll pay this year, it’s close to a $20,000 increase,” she told City Limits. “And my rent roll is down.”

The RGB reports that 53 percent of buildings with at least one stabilized unit are entirely rent-stabilized. These properties rely most heavily on RGB increases to cover their expenses, because they can’t cross-subsidize with free market apartments, according to the Community Housing Improvement Program, another landlord group. Especially since changes to state law in 2019 slashed allowable rent increases between tenancies.

Following Tuesday’s vote, CHIP executive director Jay Martin deemed the process broken. “Setting reasonable rent adjustments that will maintain affordability and the quality of roughly a million apartments should be determined by professionals and data and not the farcical display that happened this evening,” he stated.

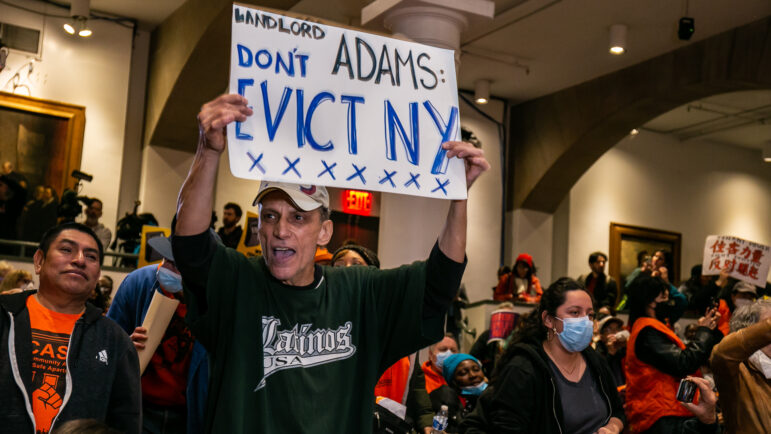

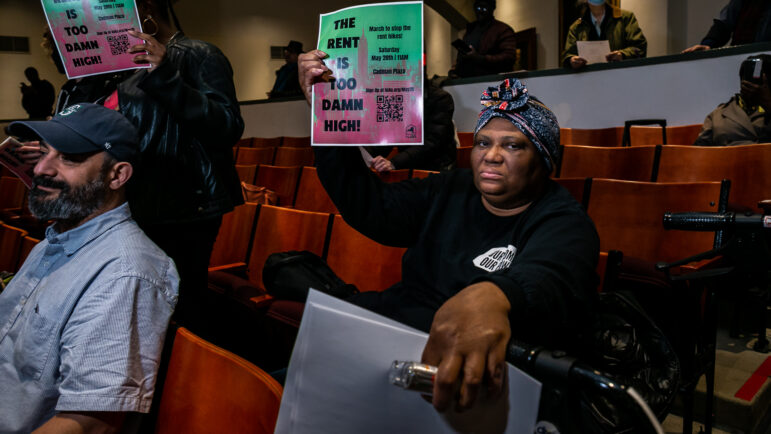

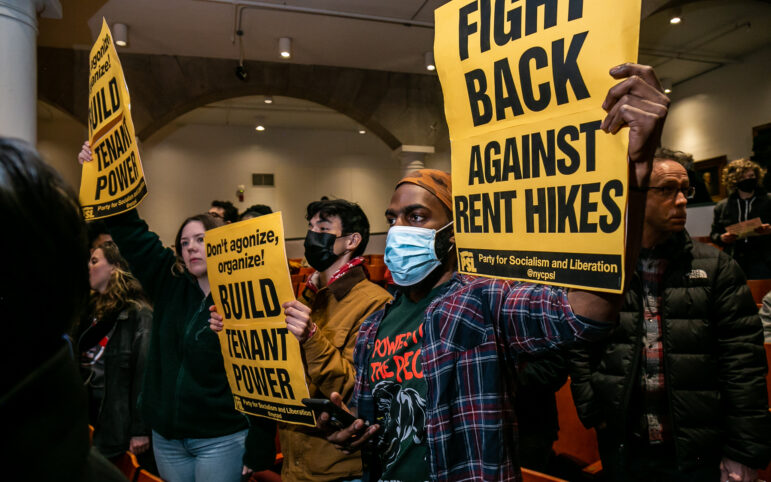

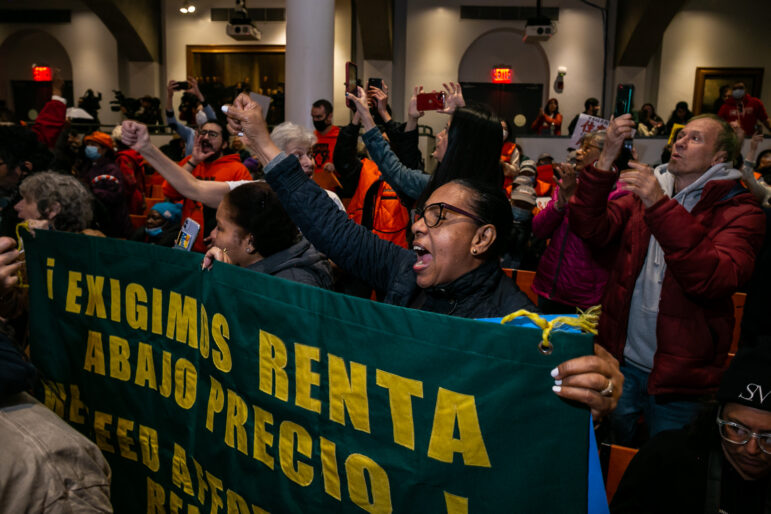

Scenes from Tuesday’s Rent Guidelines Board meeting at The Great Hall at Cooper Union.

Scenes from Tuesday’s Rent Guidelines Board meeting at The Great Hall at Cooper Union.

Scenes from Tuesday’s Rent Guidelines Board meeting at The Great Hall at Cooper Union.

Scenes from Tuesday’s Rent Guidelines Board meeting at The Great Hall at Cooper Union.

But tenant advocates urged a longer view of landlords’ economic conditions, arguing that the steep drop in operating income was a pandemic-induced aberration. They point to an RGB finding that inflation-adjusted NOI has grown almost 50 percent since 1990.

“It changes slightly from year to year, but what’s important is to look at it over time,” said Michael McKee, treasurer of the Tenants Political Action Committee. “Landlords of residential rental property in New York City have a captive audience.”

Meanwhile, record inflation in the New York City metropolitan area—6.1 percent, the highest since 1981—wiped out any wage gains for tenants, according to RGB findings. Eviction case filings also increased, though they remain below pre-pandemic levels.

According to the 2021 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey, the majority of rent stabilized tenants pay more than 30 percent of their income toward rent, meaning they cannot afford their apartments under the federal government’s standard.

Chen Ren Ping, a Chinatown tenant and leader with the the group CAAAV: Organizing Asian Communities, testified about his own difficulty paying rent at an RGB meeting late last month, speaking in Mandarin with real-time translation.

“My current rent-stabilized rent is $1,552.36. My retirement income is $794. My rent is double my income,” he said. “I am now 65 years old and should be retired, but because I need to live and pay the rent I am still working outside part-time.”

Protestors and tenant activists before and during Tuesday’s preliminary Rent Guidelines Board vote.

Protestors and tenant activists before and during Tuesday’s preliminary Rent Guidelines Board vote.

Protestors and tenant activists before and during Tuesday’s preliminary Rent Guidelines Board vote.

Protestors and tenant activists before and during Tuesday’s preliminary Rent Guidelines Board vote.

Following Tuesday’s vote, tenant attorney Leah Goodridge, a former RGB member, bemoaned the so-called commensurate rent adjustments—recent calculations released by board staff showing how much rents would have to increase for landlords to maintain a constant net operating income, assuming a building is entirely stabilized.

Though they are distinct from the board’s recommendations, the commensurates make headlines and tend to exceed the adopted preliminary ranges. This year’s went as high as 8.5 percent for a one-year lease and 16 percent for a two-year lease.

For context, a City Limits analysis of one-year adjustments going back to the 1960s shows just three increases of 8.5 percent or more—in 1968, 1974 and 1979.

“I honestly think that putting out the 16 percent… it’s sort of like a political buffer. Now we get to say, ‘Oh, well it wasn’t 16 percent,”’ Goodridge said.

A complimentary calculation is needed for tenants, according to Adán Soltren, one of the board’s current tenant members. Perhaps one that would keep them from paying more than 30 percent of their income in rent.

In the meantime, he urged tenants to pack board hearings and demand rent adjustments below the preliminary range ahead of the RGB’s final vote in June.

“What you saw here today was the bubbling over of these last couple years of really pushing tenants to the brink,” he said. “I know that other folks might have felt rattled, but this is what happens when you push people who are struggling down even further.”

3 thoughts on “NYC’s Stabilized Tenants Stare Down Further Rent Hikes, Recalling Bloomberg Era ”

The city council cannot have its cake and eat it too.

There is only one way to solve this. Landlords for rent stabilized buildings should not have to pay a 7.7 % increase in property taxes in 2023. Insurance still goes up each year which cannot be controlled.But the Landlords should get a 5% tax break for each building if they have to remain less than 5% increase in rent.

Utilities should be metered and the subsidy for it should come as part of the rent voucher, so tenants deal with the energy companies for utility increases, not the landlord.

I agree. If they want socialized rents, landlords need help with taxes at least since usually largest expense item. Everyone should chip in for lost tax revenue and then can vote for change. Rent controls hurt the poor with less apartments and services.

Just a question. Just wondering.

After they plan to evict the poor United States citizenry, including the lowly working class, the disabled, the elderly, out of their homes to rot out in the streets, do they plan to subsidize the migrants moving in to these apartments?

Just wondering.

Because they already have delayed giving food stamps to hungry citizens in NYC. The Daily News reported the delays were months long.

But they frantically scramble, they stand on their heads to feed and house the migrants.

Understand:

NYC is blessed and honored to be a sanctuary city. Yes. A blessing and an honor. This should not change.

But right now the sanctuary is being defiled by the mentality of welcoming the migrants at the cost of blood of her own citizenry.

This is evil. A righteous veneer, thinly veiled, does not a true sanctuary make.