“If the RGB is meant to protect tenants, its record is mixed at best. But the alternative, a city of free market rentals, would be much worse. How can this be explained? And what can it teach the tenants movement nationwide?”

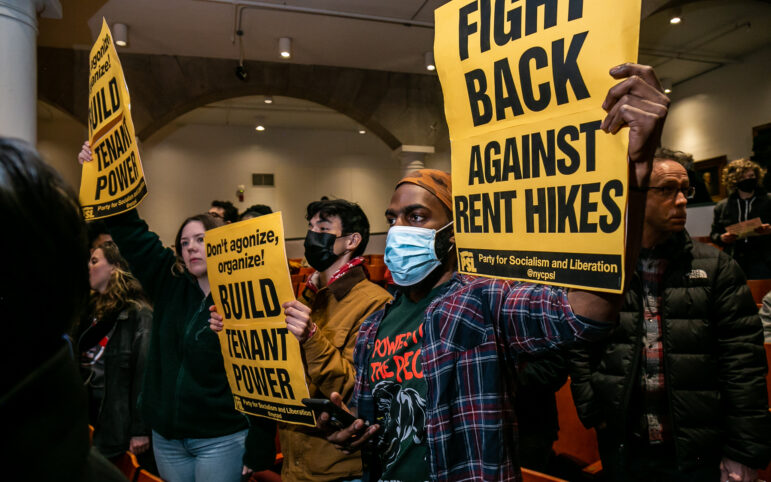

Adi Talwar

Scenes of protest at the Rent Guidelines Board meeting at The Great Hall at Cooper Union earlier this spring.New York City is the most expensive city on the planet. Despite this challenge, working class people continue to predominate, thanks in large part to a system called rent stabilization.

Close to half of the city’s homes for rent are protected from direct market pressures. Almost a million rent-stabilized apartments are spread across the city with about 2.4 million tenants, and in them, landlords can’t set rents unilaterally. Instead, a ceiling for permitted increases is set every year by an appointed panel called the Rent Guidelines Board (RGB).

However, this system is not entirely a boon for renters. In fact, this spring, the RGB has been the target of action by tenants and their allies in the City Council, as the board contemplates increases of up to 7 percent on two-year leases. Over the past 20 years, rent stabilization has failed to stop rent burdens of low-income rent-stabilized tenants from catching up with market-rate tenants.

Even in economic downturns, like the 2008 financial crash and the COVID crisis, rent-stabilized landlords have enjoyed consistent returns on investment. During this year’s hearings, counterintuitively, landlord advocates have called the RGB their “safety net,” precisely because it guarantees them a steady trajectory of ever-higher rents regardless of market conditions. Unfortunately, most board members might agree.

The RGB is an exceptional apparatus in the United States. Its members are selected by the mayor: two represent tenants, two the landlords, and five represent the general public. While in most of the country, landlords hold a tyrant’s power over rent, the RGB creates a system of arbitration that resembles tripartite arrangements—with labor, capital, and the state forced to negotiate—more commonly found in social democratic countries in Western Europe and Latin America. This might sound like a good thing: tenants get representation, with a process of bargaining under state regulation instead of a pure free market.

If the RGB is meant to protect tenants, its record is mixed at best. But the alternative, a city of free market rentals, would be much worse. How can this be explained? And what can it teach the tenants movement nationwide?

A brief history of the RGB

The RGB was established in 1968 by Mayor John Lindsay in response to popular pressure to expand rent control to post-war buildings. In its very first year, the board raised rents by 10 percent. Incongruously, some of the highest rent hikes of its history were passed in the 1970’s, a time when buildings were being abandoned by their owners and the city was nearly bankrupt. This lavish generosity to landlords is less surprising when one accounts for the fact that for the first 14 years of its existence, the RGB was actually managed by the landlord group called the Rent Stabilization Association, which still exists.

This model of industry self-regulation worked about as well as you’d expect: In the early 1980’s this system was dismantled after the New York Attorney General sued for $1 million of improperly used state funds, some which were used to lobby against the very law the RSA was meant to administer.

After that ignominious first act, the RGB was reconfigured under mayoral control. Since then, the appointed members of the board, and the rent increases they vote on, have acted as extensions of the mayor’s housing agenda. Depending on who the mayor is, that can be good or bad for tenants.

The Michael Bloomberg years delivered consistent increases to rent stabilized landlords, none more fortuitous than those of 2008, when the RGB granted increases of 4.5 percent for one-year leases and 8.5 percent on two-year leases. In the same year, the median house price dropped by 29 percent and multifamily housing was in the midst of a three-year cumulative rent decline of 7.9 percent.

Mayor Bill de Blasio shaped a more pro-tenant RGB, which even froze rents for several years of his tenure. Of course, until 2019 when legislators in Albany passed a series of reforms, it was still possible to flip apartments and remove them from rent stabilization completely. As such, landlords worked to create more vacancies, which allowed them to raise rents dramatically. However, if you could hold onto your apartment, the de Blasio years were a pretty good time for a tenant to catch their breath.

Today, Mayor Eric Adams finds himself in a tricky bind: He wants to support rent increases in 2023, but not too high. Adams, himself a landlord who has sworn to run a mayoralty in their interests, wants it both ways: protect the base of the landlords who funded his campaign, and protect the tenants who voted him into office. One of his first RGB picks certainly reflects the former pull: Arpit Gupta, from the right wing Manhattan Institute, doesn’t believe in rent control.

But the problems with the RGB go beyond the flaws of its appointed members. There are numerous structural problems.

Structural and board problems

Rent stabilized landlords have argued for rent increases because taking care of housing costs money. Indeed, New York’s aging housing stock does cost more every year to maintain. Assuming landlords do make an effort to keep up with operation and maintenance, their spending will go up in aggregate over time. However, the costs of maintenance need to be analytically distinguished from landlords’ profits and debt service (which in many cases has been inflated by the risky investment decisions made by landlords in a pre-2019 inflated market). This has not happened.

The board’s mode of research—and the coverage that surrounds it—tends to benefit landlords. They compile annual data on increases in operating costs via proxy measurements and survey data. Since landlords refuse to open their books and publicize their actual bottom lines, we don’t know how much they are spending or how much they make.

The RGB data focuses on how to keep landlords’ net operating income (NOI) in line with, or higher than, inflation and operating costs, but not how to stabilize tenants’ rent burdens. Even by this skewed standard, the RGB has favored landlords. According to Tim Collins, the RGB’s former executive director, the increases authorized by the RGB since 1990 exceeded the amounts needed to keep owners whole by over 17 percent cumulatively.

Additionally, the composition and nomination of the board is highly undemocratic and solely favors the mayor in two ways: First, the Mayor has sole control over the board. Whoever is mayor gets to select every single member of the board, and no one gets to question, challenge or confirm them.

Second, the five public members which comprise a majority have created a situation where the tenant and landlord members can cancel each other out—two minority factions of equal sides —which often leads to 5-4 votes. When this happens, the vote is entirely in the public members’ hands, and they often follow the lead of the chair, who presumably represents the will of the mayor.

A path forward

Let’s make the RGB a progressive institution that privileges tenants. Here’s how:

- Democratize the process. Model the RGB off of another powerful board that doesn’t have sole mayoral control: the City Planning Commission, in which most—but not all—appointments are made by the mayor with City Council oversight (i.e. they have to approve the choice); the rest are made by other elected officials, also with City Council oversight.

- Reform the faction problem. If we are using the tripartite bargaining model, the opposing sides should actually negotiate. One solution floated in tenants rights circles is to subtract two public members, which would force the remaining public members (including the chair) to either side with one of the other sides (tenant or landlord), or to sway one of those parties to vote with them.

- Regardless of how the board is composed, it should stick to its chartered purpose. The RGB’s founding document, the Rent Stabilization Law of 1969, states that the board’s purpose is to “prevent speculative, unwarranted and abnormal increases in rents” and “forestall profiteering” that might “produce threats to the public health, safety and general welfare.” If the RGB followed this part of their mission, tenants might be looking at rent rollbacks—not increases.

- Overhaul the research methods. The misleading calculation of landlord costs should be done away with entirely, but if it needs to stay, a similar calculation should be done to show tenant costs.

If New York leadership wants to stabilize the city’s economy and provide affordable housing for New Yorkers, it must re-prioritize the rights of tenants. Rent adjustments should be lightening the burdens borne by tenants instead of guaranteeing continued profits to landlords.

Strengthening the RGB to the benefit of tenants could serve a valuable lesson about how the national housing movement can build durable political structures—and replicate the RGB—to protect tenants nationwide.

Avi Garelick and Andrew Schustek are researchers and writers based in New York City