“Unlike other data that reveals key insight on educational improvement—such as student attendance, academic performance, class size and the credentials of teachers and leaders—what curricula is being used in city schools is often unknown, in effect a black box. This makes it difficult to learn or study how curriculum choices and professional learning impact children’s learning.”

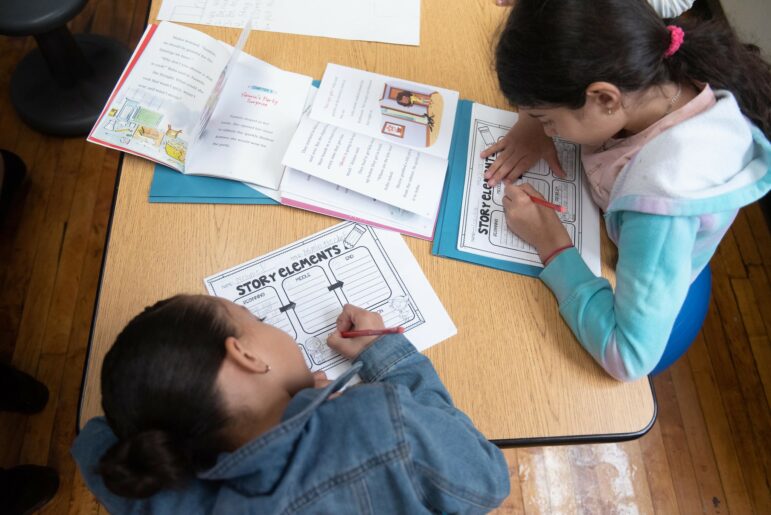

Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

Students at work in a Manhattan school in 2022.A recent article shared data on the curricula being used in over 600 New York City schools. While this might not seem revolutionary, the authors explained how this data took three years to access, was incomplete (only 600 of 800 elementary schools reported data) and is now woefully out of date. It revealed an important challenge in advancing a quality public education for our students: we generally have no idea what curricula are being taught in each of our 1800+ city’s schools.

Currently, only 1 in 3 of the city’s Black and Latinx students, who make up 65 percent of the student population, are proficient in reading, compared to 67 percent of their White peers. Without intervention, the gap will only widen. Research shows that using a high-quality curriculum accompanied with quality, team-based professional learning for teachers, can be a powerful boost to student achievement.

The impact of adopting a high-quality curriculum is even greater when you add efforts to engage families and use technology meaningfully. A study of nine school systems across seven states found that students who had access to tech-enabled, high-quality curriculum and were receiving support at home during the pandemic were learning about the same—and sometimes more—than they would have in a more “typical” year. That is in stark contrast to the nearly 49 percent of students nationally who are still struggling to get on grade level after more than two years of COVID-induced learning interruptions.

Yet, unlike other data that reveals key insight on educational improvement—such as student attendance, academic performance, class size and the credentials of teachers and leaders—what curricula is being used in schools is often unknown, in effect a black box. This makes it difficult to learn or study how curriculum choices and professional learning impact children’s learning.

In New York City, curriculum selection has historically been a decision delegated to the more than 1,800 individual schools. School leaders and their teams have been able to choose to implement published curricula, to adjust published curricula to meet the needs of their students, to knit together many different curricula, or to author their own curricula in grade or content teams, or even on a classroom-by-classroom basis.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. Choice and diversity of options can be a powerful strategy that leverages the deep knowledge and expertise in our diverse schools and communities. The challenge, however, is that without transparency about what content is being used, and how, it is nearly impossible to bring together all the additional supports a school needs into one coherent model—professional learning, assessment, policies, research—and thus create the best learning opportunities for our children.

The good news is that New York City Public Schools (NYCPS) is taking significant and bold steps to shift schools to high-quality, curriculum-supported learning environments. Over the past few months, the administration has made high-quality, evidence-based curriculum—especially for literacy—a cornerstone of its effort to improve instruction across all five boroughs.

But those efforts will have limited impact in the absence of accurate and transparent information about which curricula schools are using and how. Unsealing that black box of information will vastly increase the opportunities for collaboration, contribution, informed decision-making, and strategic equity work.

We are not claiming sourcing and sharing data from 1,800 schools is easy. But NYCPS has acknowledged the need for this information, as have stakeholders across the ecosystem— teachers unions, community-based organizations, family and teacher advocacy groups, indicating broad support.

The city’s school system should build on this support to publish the curricula on school webpages and make the data available as a transparent dataset that can be analyzed, organized and queried. This will enable school leaders to share lessons and resources, and families to engage more deeply in their children’s education. It will also enable researchers, providers, and philanthropies to align efforts and ensure every school, classroom, teacher and family has the resources they need to educate New York City’s children.

A strong public education can provide every child a pathway to lifelong opportunity and success. With real-time visibility into the material being taught in our classrooms, we can unlock opportunities for collaboration and critical insight to help make that promise a reality for the 1 million students in the city’s schools.

Lynette Guastaferro is the CEO at Teaching Matters. Amber Oliver is the managing director at the Robin Hood Learning + Technology Fund.