In a budget resolution unveiled last week, the State Senate earmarked $389 million for public housing and Section 8 tenants statewide who applied for, but were left out from, New York’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP). The Assembly proposed $385 million for the same purpose.

NYS Legislature

Lawmakers and public housing advocates at a March 9 rally in Albany calling for extra ERAP funds.Albany lawmakers are proposing additional budget money to go towards public housing and Section 8 rent arrears across the state—but with NYCHA tenants alone owing more than $466 million in back rent, it’s still not enough for the local housing authority to rid its debt.

In a budget resolution unveiled last week, the State Senate earmarked $389 million for public housing and Section 8 tenants statewide who applied for, but were left out from, New York’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP). The Assembly proposed $385 million for the same purpose.

Despite being eligible for ERAP, which kicked off in 2021 to aid tenants behind on their rent because of the pandemic, public housing and Section 8 residents were given low priority when the state implemented the program.

More than 31,000 NYCHA households alone have applied to ERAP but have yet to access the aid, since the program put public housing tenants at “the back of the line,” according to State Sen. Brian Kavanagh.

“This is a problem that was created by state law,” said Kavanagh, who rallied earlier this month alongside Assemblymember Grace Lee in calling for the additional ERAP money in the budget. “It wasn’t right when we did it.”

Lawmakers have until April 1 to negotiate a final spending plan with Gov. Kathy Hochul, who didn’t set aside any additional funding for ERAP in her own $227 billion budget proposal.

ERAP still has $347 million on hand after closing its application portal in January, enough to cover the remaining applications submitted by tenants in private-market apartments, officials said. The additional $389 million Senate lawmakers are asking for, if approved, would be enough to cover every eligible ERAP applicant, including those in public housing, according to Kavanagh.

But it won’t be a silver bullet fix for NYCHA, where more than 73,000 households are collectively $466 million behind on rent, a number that’s quadrupled since 2019, officials testified at a New York City Council hearing last week.

“All of the arrears are not ERAP eligible so even after we do this, NYCHA, Section 8 providers and their tenants will still have arrears,” Kavanagh said. “That has to be addressed as well and I think that the federal and city governments should play a role.”

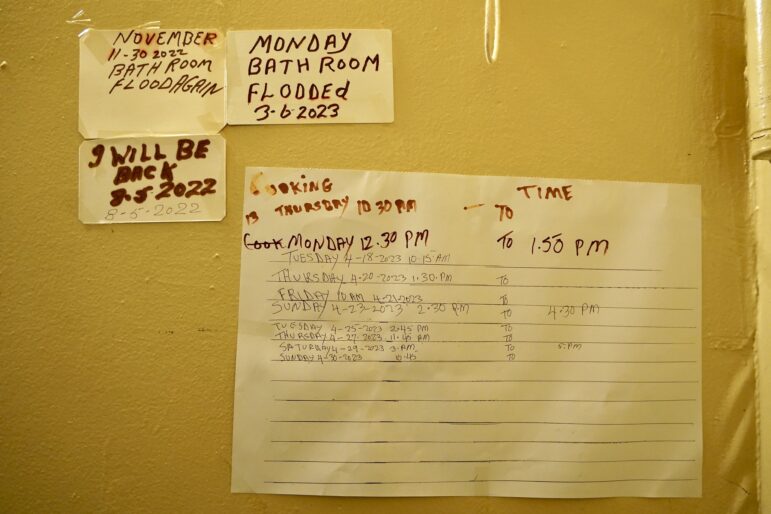

The lack of rent revenue could result in cuts that would further delay anticipated projects and repairs at NYCHA, officials have warned. Since 2019, NYCHA has been under the watchful eye of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), part of an agreement to address much needed maintenance issues like mold, broken elevators and leaky roofs.

“Without additional funding or an increase in rent payments beginning next year, NYCHA will have no choice but to significantly cut expenses and curtail repairs, including those related to the HUD agreement,” NYCHA’s Interim Chief Executive Officer Lisa Bova-Hiatt said during last week’s City Council hearing.

Over the last 12 months, she said, NYCHA collected just 64 percent of rent from tenants, which makes up a third of NYCHA’s operating budget. The decline is jeopardizing the housing authority’s ability to stabilize its crumbling infrastructure, which has suffered decades of government underfunding.

“We rely on rent payments along with federal funding to maintain our developments which are aging rapidly and have more than $40 billion in major capital needs,” said Bova-Hiatt.

The plan now, Bova-Hiatt said, is to work with tenants to keep them housed by getting them on a payment plan or connecting them with rental assistance like the city’s One Shot Deal.

NYCHA tenants account for $121 million worth of pending ERAP applications.

“We know that many public and subsidized housing tenants accrued rent arrears because they were unable to pay due to the hardships imposed on them by the COVID-19 pandemic,” Kavanagh said. “They shouldn’t be forced to bear the burden of this debt because they weren’t placed on equal footing with their fellow New Yorkers.”