Sadef Kully

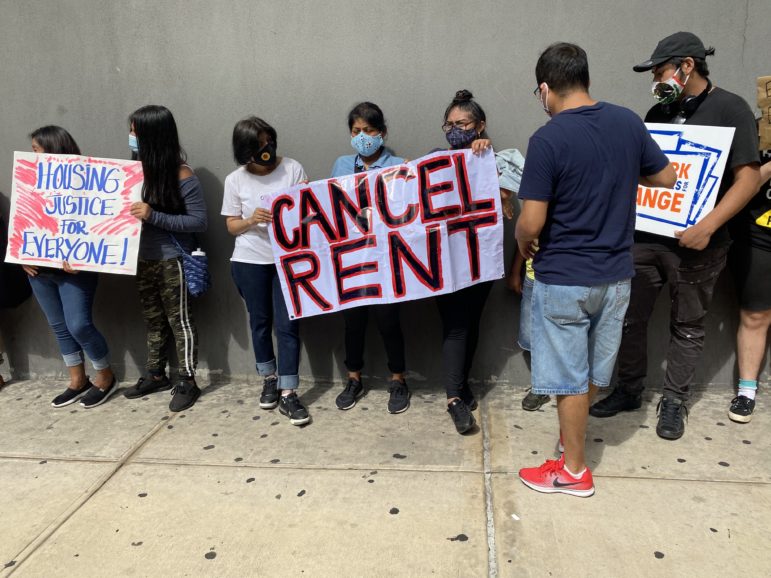

The scene from a June protest by Housing Justice for All.Taren Payne, a recent social work school grad, has so far helped 32 of her Harlem neighbors apply for assistance through New York’s new $2.4 billion rent relief program.

For weeks, the older adult applicants heard nothing about their submissions—until, that is, Payne got an email notice for one of the tenants and decided to help the others check their spam folders. It turned out that the Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance (OTDA), the agency administering the program, had informed the renters that they needed to submit copies of their lease agreements to complete their applications.

“If it hadn’t happened directly with me, I wouldn’t have known they were asking for more information,” she says. “I found you have to be more involved with the process.”

Nonprofit legal service providers across New York City say they’re facing the same communication issues—multiplied by hundreds or even thousands of applicants. With seven weeks to go before state eviction protections expire, New York’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) has yet to cut a single check, and the organizations tasked with helping tenants say they’re hamstrung by inefficiencies as they work to help thousands submit their required forms.

“The applications we’re assisting with, we’re just blind,” says Scott Auwarter, assistant executive director at BronxWorks, one of nearly 30 organizations that outlined the problems in a letter to the state’s OTDA. “If there’s a problem, they’ll notify the tenant, but they won’t notify us.”

The ERAP process has been criticized for technical and structural flaws since its launch June 1, two months after state lawmakers set aside federal funding to reimburse landlords whose low- and middle-income tenants missed rent payments as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Chief among the issues: a concern that the online-only application process disadvantages people without internet access, computer literacy or English proficiency.

That’s where nonprofit groups and housing advocates come in, helping people make sense of the process and navigating an often daunting application. They have asked OTDA to provide access to a special account that would allow them to review all of the applications they helped clients submit and to share, with client consent, notifications sent to the applicants they assist.

OTDA met with the providers for a tightly-controlled virtual presentation earlier this month, but have not instituted the proposed reforms.

Despite the many issues, OTDA says the portal is clearly working: New Yorkers submitted 119,209 applications over the first month, including 91,457 forms to cover back rent in New York City, according to the agency’s June summary report, which says some people have made duplicate submissions.

“The more than 100,000 applications already received are being reviewed and prioritized, with the first payments expected to go out in the coming weeks,” says OTDA spokesperson Anthony Farmer.

Nonprofit officials question how many of those applications are actually invalid.

“We see the big number they have but we don’t know how many of those are duplicate applications and invalid applications. And they’re not going to know what’s invalid or not because they’re processing it now,” said attorney Justin La Mort, a supervisor at the organization Mobilization For Justice.

“A lot of this will depend on how they go about making approvals. We’ve gotten some feedback on documents, but we haven’t started getting denials or acceptances yet,” he added.

In response to a question about the valid submissions, Farmer, the OTDA spokesperson, provided a version of his previous statement and pointed to the monthly reports mandated by the state legislature.

State Sen. Brian Kavanagh, who sponsored legislation to create a rental relief program, says he has encouraged OTDA to take up advocates’ calls for improvement.

“They’ve been slow to set up a process where they’re getting the full range of feedback,” Kavanagh says. “They’ve had active discussions with certain organizations, but earlier in this process they should have set up a town hall meeting structure. These are organizations that are actually contracted by the government to do this work and they’re not feeling that OTDA is hearing them.”

He says he is disappointed that the state has yet to allocate any funding but believes OTDA when they say they’ll soon start sending money to landlords. Those checks will restore confidence in the program, he says.

“The system is receiving about 4,000 applications a day and it’s critical that the $2.4 billion we allocated for this program get out the door,” Kavanagh says, adding that he thinks OTDA will overlook minor flaws with applications. “They understand the goal is to get relief into people’s hands and not to have an overly restrictive interpretation of the law.”

A litany of inefficiencies

BronxWorks is one of 11 organizations across the five boroughs that will receive a total of $22 million dollars from New York City’s Human Resources Administration (HRA) to step up application assistance. The money will go toward hiring extra staff to help tenants complete their forms and target outreach in underserved communities.

A spokesperson for the Department of Social Services (DSS), which oversees HRA, said the state provided the money for the city to distribute to the nonprofits, along with an additional $2 million to pay for promotion, educational workshops and other services. BronxWorks has not yet received the nearly $5.2 million included in its contract and DSS says they expect the city will pay them by the end of the month.

Auwarter says he is confident the money will come through, but adds that the structure of the state program makes it hard for organizations like his to identify and solve recurring issues, even when they hire more staff members to work with applicants.

“At a certain point, there’s going to be a significant amount of money invested in groups like ours but we can’t see anything, we can’t keep track, we can’t see if we’re successful or not,” he says. “It just seems strange. How are we supposed to hold ourselves accountable? How do we know if we have someone making the same mistake over and over and over again?”

BronxWorks and 28 other organizations raised that issue in their letter to OTDA July 3. They said the current program structure excludes the New Yorkers most at risk of becoming homeless, like people earning below 50 percent of Area Median Income ($59,650 for a family of four, $41,800 for a single person), people with serious illnesses and disabilities, and older adults, who are less likely to have reliable internet access or the tech skills to navigate an application process that takes over an hour, and must be completed in one sitting.

They also pointed out the inefficiencies affecting the organizations helping hundreds or even thousands of applicants, like a lack of zip code-level data that would allow them to focus outreach in areas where relatively few people have applied. Still, the organizations have a general idea of where to target their efforts: Eviction filings have spiked in the very same low-income communities of color where COVID-19 rates have been highest, like Corona, Queens and much of the Bronx, according to data mapped by the Eviction Lab.

The applications are crucial for halting an eviction. By submitting their forms, tenants and landlords freeze housing court eviction proceedings and monetary judgements, but first, the judge must know about the application.

There is no uniform document to demonstrate that, but Legal Aid Society staff attorney Ellen Davidson says tenants have stayed their cases by providing their ERAP application number to the court or by showing the judge an email saying they successfully applied. Legal Aid was one of the groups that signed the letter to OTDA.

La Mort, the supervising attorney at Mobilization For Justice, said he too has encountered judges willing to accept informal proof or who will use a tenant’s application number and date of birth to verify their submission and stay their case.

When asked about proof of application in Housing Court, Farmer, the OTDA spokesperson, pointed to the Frequently Asked Questions section of the ERAP website indicating that tenants will receive written notification of the available rental assistance even if their landlords do not respond. They may present the notification in Housing Court as a defense to stop monetary judgements or evictions based on non-payment of rent during the pandemic months covered by ERAP.

In their letter and in interviews, the nonprofit providers highlighted a number of other issues they say make the process prone to error and opacity.

Jose Abrigo, a supervising attorney at Manhattan Legal Services, says OTDA does not send a confirmation to let people know they have completed their application correctly and he worries many people will have to fix their submissions weeks or months later.

“You kind of submit an application into the ether and hope you did it correctly,” Abrigo says.

He says he hopes state officials are flexible when it comes to approving applications.

“ERAP is really great and provides a lot of great protections and we realize OTDA had to cobble this together in a rush to implement this for hundreds of thousands of people. But that being said, the system is pretty buggy,” he says. “We’re hoping that OTDA, because the process wasn’t articulated clearly, they’d be pretty forgiving and would be willing to amend those mistakes.”

The letter to OTDA urged the agency to provide applicants with a copy of their completed forms so they can determine what information or documents they may have missed or how their submission differed from the materials sent in by landlords.

And the groups asked OTDA to provide an explicit time frame for when applicants will learn if they have been approved or denied.

“An important part of our advocacy is to inform tenants what to expect once we have submitted their ERAP application so they can rest assured that the process is transparent and fair,” the letter states.

Representatives from the various organizations attended a virtual session with OTDA officials on July 8 to discuss the issues, but three attendees described a WebEx presentation that left participants unable to see who else was in the meeting or what questions had been entered into a chat window.

“The agency has undertaken an unprecedented effort to establish partnerships with local governments across the state and welcomes any input we receive from community-based organizations—especially those groups actively involved in helping New Yorkers apply for this critical assistance,” said Farmer, the OTDA spokesperson.

Landlord groups have also described persistent problems with the application process, like the inability to save progress and resume at a later time and the challenge of tracking potentially hundreds of forms.

The wait is only compounding debts for small property owners and their tenants, says Community Housing Improvement Program Executive Director Jay Martin, whose organization represents small landlords accounting for hundreds of thousands of rent-stabilized units.

He said he fears another extension of current eviction protections, which would plunge tenants and landlords into deeper financial troubles. The current freeze expires Aug. 31.

“We can’t keep extending the eviction moratorium because we’re not solving any problems, we’re just adding debts,” Martin said. “This is debt they have to worry about and could haunt people for decades.”

Martin criticized the slow process and the lack of pay outs, three months after the state included ERAP in the latest budget.

“It’s bad politics. If I’m a politician and say I have $2 billion to help you I want to get this money out as soon as possible to be a hero,” Martin said. “It’s been a disaster.”

22 thoughts on “NY’s Rent Relief Program Has Yet to Cut a Check Amid Inefficiencies and Frustrations”

Don’t know how this process is going to get any better. The state is changing what tenants and landlords need to submit every two days. They launched a process with no process and logic or direction. Tenants and landlords are scrambling for a piece of the 2.5 available Billion dollars. And whomever is in charge has no clue.

It’s like staring into a void.

Hubby & l are seniors who are relatively internet savvy. Our adjusted gross is below the 50% AMI, even tho we don’t live in an ‘underserved’ zip code.

I applied on June 4th.

Every time l call to check the status of our application a different rep will tell me something different. Including several times telling me l had to re-apply.

And then the next rep telling me no, the application is complete and the last time l called l was assured it’s pending and now we just need to wait to get approved or denied.

But…my landlord’s rep is being told their info is missing from my portion of the application.

I’d been over & over that info many times & kept notes of every call/conversation.

And been told it IS there.

It’s getting scary because the financial situation is still way behind.

What are we to do?

Having a bureaucratic void is really difficult for seniors so far in arrears.

How do we get answers?

Hi Nancy, I’m sorry you’re having those difficulties. Could you email me at david@citylimits.org

Well, from what I understand is that we are one of only a handful of states which has not released any emergency rental assistance. For a state that claims to be so progressive and concerned for the poor; this doe’s not look good. How can other states get the ball rolling in an efficient manner and not New York?

It’s upsetting I applied June 1 submitted all the documents several times. I call every other week and all I get is an attitude from the agents and wrong information. The urgency is lacking I’ve been waiting for 8 weeks now. I was told by an agent it’s only 7 weeks what’s the rush. I guess she’s rich and doesn’t understand homelessness.

Hi Tricia, I’m sorry you’re having those difficulties. Could you email me at david@citylimits.org

This process has been ridiculous!! I’m A 42-year-old financial student that works for a very small accou. nting company. I was the last person hired by the company so I was the first one let go at the onset of the pandemic. I have been receiving unemployment, but it’s nowhere near what I need to pay rent. I haven’t entirely not paid my rent but I’ve been paying between a third and a half of it each month, I started trying to get into the portal immediately on June 1st but it didn’t even work to let you into the application until at least the 4th or 5th. At that point I started an application but because I didn’t sign in and create an account I was not able to stop the application to get the documents I needed. So I got all the documents, I created an account, and did an entire other application. So I am one of those people with duplicate applications, and I just received an email this week stating so. My landlord was frustrated and I even needed to help him get together the documentation that he needed to submit. It seems like an extremely long process that is getting us nowhere!! Up until the pandemic I’ve never been laid on my rent, my credit score is over 750, and I’m not in an underserved neighborhood… Now my fear is even though I made well under the $41,000 last year, I’ll be pushed to the back because I live in Bay ridge and have paid part of my rent. Frustrating is the nicest word I can think of. Here’s to helping I get caught up and don’t have rent debt to add to student loan debt 🙄

Sarah B

It’s so frustrating, I apply on June 2 or 3 and still waiting! I called them and they said my landlord hasn’t provided there info but the landlord had called me for my application number and date of birth ! Not sure what’s going on I have 4 kids and I am very worry!!

The fact that arrears are required, with no consideration for the fact that many people, just to be fair to their landlords and to honor the lease agreement they signed, went into all kinds of debt (whether it be credit cards, a personal loan – if they qualify for either of these things, or just borrowing from friends or family) to stay current on their rent, even though it might have been barely possible most of the time, is really absurd. I understand that we need to help the people who didn’t even have that ability pay back what they owe to avoid eviction, but to have the only rent relief program now completely disqualify those who DID find some way to scrape together their payment and stay current is a horrible thing that no one seems to be discussing. I have been getting dozens of stories from people who now regret having paid their rent, people who went without ANY health insurance because they had to choose between COBRA and rent, and now it turns out they could’ve skipped on rent all this time and the state would cover it. There needs to be a way for the people who took debt, or whose health was at risk taking two crappy jobs when their real career was destroyed by Covid shutdowns, to recover some of that money. (Even the prospective 3 months you could receive is not available unless you have arrears already).

To me this is egregious and totally out of touch with reality. I have been baffled that I don’t see more outrage about that part of it.

Agree 100% I struggled to pay every utility and rent …. My landlord refinanced to be able to help me …. I have now a lot of credit card debt for bills. People have helped me … but on paper we can’t show the struggle. Unfair

My application status says — Pending Quality Cont — What does it means ? Applied june 1st. submit all documents from me & my landlord. Still pending. I don’t know its gone approve or not ?

We have to pay the landlord the water bill portion of our rent,added onto rent bill monthly. We fell behind on the waterbill portion but all rent is paid. We applied. We’re very low income. The municipal water is very bad and not safe to drink. We buy bottled water for consumption. Since the pendemic, bottle water has creeped up in cost along with everything else, causing our low income to deplete more and more and struggle harder than ever. We got all documents, id’s, and cost of what we owe in. They show at OTDA,EARP that everything is in but sits pending. When we called, we were given three different explanations, a run around basically,wrong information from of the agents and nothing since. Our landlord is tired of being a landlord. They want to sell while houses are high priced…We have been trying to buy it but had to go through the program,take the class,jump through hoops and still trying to get through everything. We could end up homeless over this. We have no where to move nor can we afford to move or rent another place. We’re disabled so our options are less than others. We need help and not getting it with through the 2 billion provided to New York.

To “PM” who claims some people had to choose between COBRA and rent when they were let go due to the pandemic emergency and financial crisis that followed, Sir that is an absolutely FALSEHOOD. Every NYer who lost their jobs received MEDICAID and SNAP Benefits especially if they had minor children. As far as rent arrears are concerned, mind YOUR business and pat yourself on the back. Some of us have serious illnesses and were forced to purchase masks (PPE) and cleaning supplies and hazmat suits at a PREMIUM COST during the roughest stages of the pandemic lockdown. Out of touch with reality? Coats skyrocketed in my community because of supply/demand breakdowns. The fact that you are salty about families in dire need getting assistance demonstrates all that is wrong with this Nation.

I just read this a few minutes before posting this comment. Im curious if anyone has received an acceptance or better yet, got their rent paid already? I submitted everything since 6/16 and all it says is pending owner documents but they’re all there.

almost nobody at all

My owner status says active with risk. there are no explanations I have no clue what that means and my app status has been document review com for weeks.. ugh june 3rd applicant here

Same here Documents reviewed com, applied June 1st and absolutely no changes. Just at a stand still😬

I applied June 6. All paperwork has been submitted. Everything says clear except owner status first it said hold now it says risk alert. What does that mean.

I applied for rental assistance(tenant) two weeks ago & owner portal done by landlord front of me last week.

They created the sign in and upload all documents with the assistance of OTDA representative online(over the phone online)

The representative of OTDA says the paemt will be deposited within 4-6 weeks.

Both parties of the documents went thru successfully .

BUT we didn’t get any call from OTDA about any missing docs or approval.

How can we get informed? Whom we contact ? We 4 members family. Need firm replay. If anybody recieve OTDA rental assistance? Let us know.

Waiting since June, no money from ERAP, tenants stopped paying the rent. No info if they get approved or denied. Rude and not helpful customer service, asking for tenants personal email and cell number if called early in the morning …

This program fails landlords and creates many opportunities to abuse the system .

Applied since beginning of June, neither money or response received yet. 4 weeks ago I called and was told the application was in final review stage, still no result after four weeks passing by.

I have applied for ERAP program on 6/30/2021 and when I called to check my status and I was told that NYCHA tenants are LAST on the list because the people that are not living in NYC Housing will be first. I was also told that the ERAP funds might not be enough to help the people in NYCHA cause its not really for NYCHA. THAT”S WHAT I WAS TOLD WHEN I CALLED.