The opening of the long-awaited Emergency Rental Assistance Program was marred by technical glitches and error messages on the state’s online application portal.

Sadef Kully

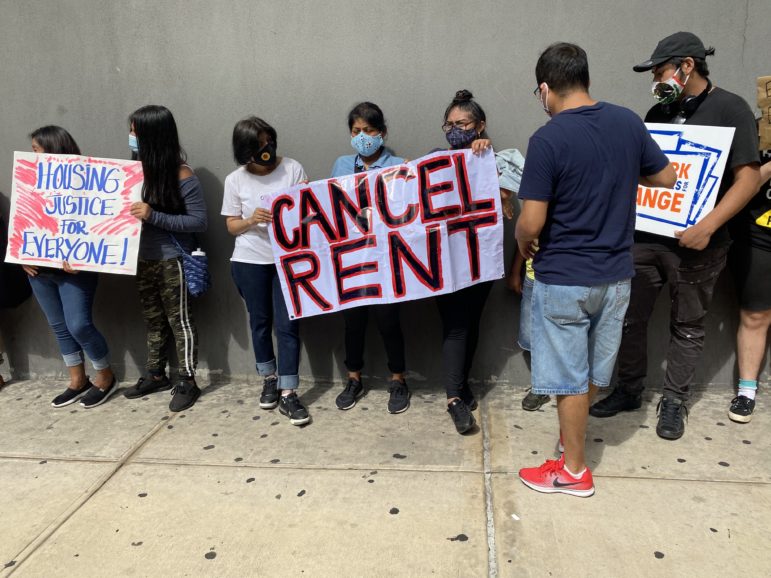

A June rally by the tenant organization Housing Justice for All. Many New Yorkers have had trouble paying rent since the start of the pandemic.For Robert W. of Westchester, the state’s new rent relief program is a chance to cover five months of arrears and get his family back on firmer financial footing after a lay-off and a furlough sunk their income.

He owes his landlord $10,500, and he hoped to become one of the first New Yorkers to apply for the state’s brand new Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP), which opened Tuesday and will send cash to landlords on behalf of tenants impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Glitches with the state-run online form prevented him from getting the application in by 4 p.m. Tuesday, but Robert kept a positive attitude. The assistance will mean “a lot less worry about some upcoming medical expenses and a planned operation for somebody in my family,” he says (he asked not to use his last name for fear of future retaliation from landlords and associates). “We can get back on track in a few months if some professional changes work out.”

Despite several tech issues and errors, the state’s Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance (OTDA) said more than 7,000 people applied for the program in the first four hours after it opened Tuesday. ERAP, created with more than $2 billion in COVID relief funds from the federal government, will send money directly to landlords whose low- to middle-income tenants demonstrate they could not pay rent as a result of the pandemic. Lower income New Yorkers—people earning less than 50 percent of Area Median Income—and renters already facing eviction have priority during the first month.

Legal service providers and advocates say they are unsure just how many people will come to them for assistance, but they agree on the general estimate: a lot.

Between April 16th and 28th, more than a third of respondents across New York state said they were behind on their rent or mortgage and that they considered eviction or foreclosure “very likely” or “somewhat likely” over the next two months, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s PULSE survey.

The launch of the program Tuesday corresponded with an all-hands-on-deck effort to connect New Yorkers with crucial rental assistance.

Six of New York City’s largest nonprofit legal service providers and tenants rights’ groups kicked off a Know Your Rights campaign and housing helpline— 212-298-3490—to reach immigrant tenants, including undocumented residents, to educate them about ERAP. The effort involves the Legal Aid Society, Enterprise Community Partners, Make the Road New York, RiseBoro Community Partnership, CAMBA, and funding from the Robin Hood Foundation.

“We know that throughout the year, it has been particularly hard for immigrants without status and mixed-status families to apply for assistance, and we wanted to make sure there was extra help available,” said Legal Aid Society Staff Attorney Ellen Davidson.

Applicants do not need to prove their citizenship or legal status to apply for the funds.

Many of the organizations involved in the new helpline said they had already begun reaching out to clients and helping them prepare the information they need to submit. Government identification, rent receipts and formal leases work best, but OTDA will also accept landlord “attestations”—letters stating that a tenant did not pay their rent—and other documents, like baptism records, as ID.

READ MORE: What to Know to Apply for New York Rent Relief

Immigrants are most likely to need those more informal documents to access funds, says attorney Ju-Bum Cha of the MinKwon Center, a nonprofit that primarily serves the Korean community. But landlords may not comply with self-attestation because they collect rent in cash and decline to report the exact total on their tax forms, he says.

“It’s a gray area,” he says, and that’s where legal assistance will be crucial. “Since early May, we have been receiving 10 to 15 inquiries every day.”

The fits and starts on day one of the online application process frustrated landlords and tenants alike, who posted messages to OTDA explaining their problems on Twitter and Facebook. A landlord of a two-family home in Holbrook told City Limits he twice called the agency after receiving error messages and was put on hold for more than a half hour both times. The landlord, a man named Bogdan who asked not to use his last name, said the family renting his apartment owes him $35,000. The lack of rental income has left him unable to pay his mortgage with a balloon payment approaching.

Taren Payne, a recent social work school grad who lives in Harlem, said she attempted to help 25 of her neighbors apply, but wasn’t able to assist in submitting a single application after trying for hours.

“We have a huge population of elderly people who were furloughed and lost their jobs,” she says. “I had all their documentation ready and it didn’t work.”

On Twitter, OTDA suggested that applicants who receive error messages should “clear their browser’s history, including cookies and cached data and images.” Some users replied that the quick fix worked for them. It didn’t work for Payne.

“To see this kind of inefficiency and ineffectiveness, you’d think they’d know better,” she said.

Justin La Mort, a housing attorney with the organization Mobilization For Justice (MFJ), said he took a cautious view heading into the first day of applications, especially after the state’s earlier, much smaller, rent relief website immediately crashed last July. That didn’t happen this time around—a low barrier for success, but a good start nonetheless, La Mort said.

“I kind of planned for this to be an experiment day and then hopefully they can figure it out on their end,” he added.

Over the next several weeks, MFJ and other organizations across the state will be working to connect as many people as possible to the program in order to keep them in their homes, he said. Existing eviction protections expire in August.

“We don’t know how many people will reach out to us proactively,” La Mort says. “So we’re going to be doing a lot of presentations with community organizations and local electeds just to try to spread the word.”

2 thoughts on “Over 7,000 New Yorkers Apply for COVID Rent Relief in Program’s First Four Hours”

The rent relief program sucks my 10 year old son could write a better program nys Error Error Error

The process is taking too long. It has been six weeks already and people are still in pending status. Once the criteria has been met, the checks should be automatically generated. It shouldn’t take six weeks to verify documents and issue a check. What are our elected officials doing about this?