A new report describes the path to social housing in New York through 20 policy proposals, from overhauling the property tax code and abolishing the city’s tax lien sale to cracking down on landlord violations and boosting public funding for tenant organizing.

Sadef Ali Kully

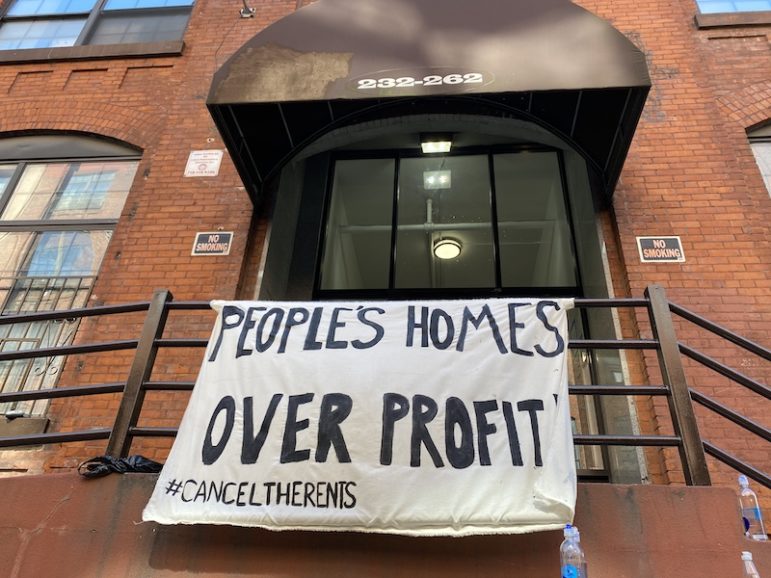

A sign protesting rent collections in Brooklyn during the height of the Coronavirus epidemic.Councilmember Tiffany Cabán’s support for an Astoria upzoning that paves the way for three tall residential towers reverberated through New York City housing circles in September.

Here was a left-wing lawmaker backing a largely market-rate complex on vacant lots, a fact embraced by pro-development YIMBY, or “Yes In My Backyard,” groups, local elected officials weighing in on unrelated rezoning proposals and even Mayor Eric Adams.

But Cabán’s stance was more nuanced than a simple “yes” or “no” on a new development. In a speech explaining her decision, she described the project in pragmatic terms—it was either the towers or the kind of development, like an Amazon warehouse, that would do nothing to address the city’s deep housing needs.

Moving forward, she added, New York City needed more equitable and affordable development divorced from the kind of speculation and profit-seeking that drives the real estate industry, leading to record-high rents and sale prices.

“I’m a SHIMBY,” Cabán said in an interview last month. “Social housing in my backyard, all day, every day.”

Social housing is the term for permanently affordable, resident-controlled buildings where tenants usually pay a fixed percentage of their income, regardless of their wealth. At its core, social housing treats homes as a public good—places to live in—rather than a private commodity to be sold and resold for ever-increasing profit. It’s common in major European cities, but is also akin to public housing, the Mitchell-Lama program and mutual housing associations that guarantee permanently affordable apartments and co-ops.

“We deserve a housing system where every single New Yorker, no matter their level of income, has a comfortable home, on a guaranteed basis,” Cabán said. “We deserve sustainable, high quality social housing, owned and managed by the people who live there, in conjunction with the public.”

The Queens councilmember is just the latest candidate or elected official to focus on the model. Social housing was central to former mayoral candidate Diane Morales’ campaign, and also embraced by former Comptroller Scott Stringer.

Now, a new report from the Community Service Society (CSS, a City Limits funder), co-authored by policy experts from the City Comptroller’s Office and University Neighborhood Housing Program (UNHP), outlines how the city can pursue a path to social housing through 20 policy proposals —from overhauling the property tax code and abolishing the city’s tax lien sale to cracking down on landlord violations and boosting public funding for tenant organizing.

“Without a major intervention, our current housing and lending policies create an environment for further waves of gentrification and displacement,” the report’s authors write.

Social housing has three pillars, they add: permanent and deep affordability; “decommodification,” or protecting homes against real estate speculation; and “democratic management,” or buildings controlled by decision-making residents.

There are already several examples of social housing for low- and middle-income New Yorkers that “people really love,” said CSS Housing Policy Analyst Sam Stein, one of the report’s authors. They include Mitchell Lama housing, Housing Development Fund Corporation (HDFC) cooperatives and the growing number of Community Land Trusts, where nonprofit organizations own the land where they lease apartments or limit sale prices.

New social housing development typically requires public land and financing, as well as a shifting perspective on housing and real estate. The points outlined in the plan create an environment where the protections provided by social housing become the norm, Stein said.

“The argument we’re building in this report is that it’s not just about social housing as the ends, it’s about the means of getting there,” Stein said. “And the means of getting there look a lot like the housing justice campaigns we’re all involved in…These are mutually reinforcing and not competing policy agendas.”

David Brand

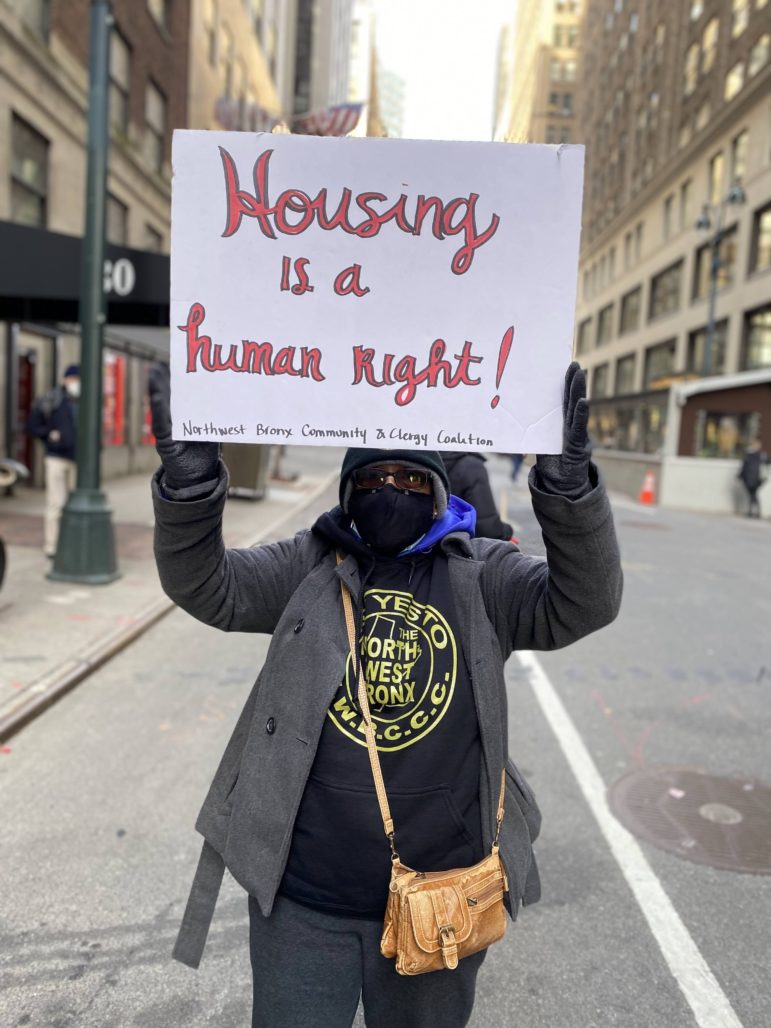

Housing activists rallied for state lawmakers to pass “good cause” eviction legislation in January.The report specifically calls on the state to foster resident control of housing through programs like the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) and Community Opportunity to Purchase Act, which would give existing tenants and nonprofit developers the first chance to buy properties.

They also recommend that the city and state institute taxes on little-used homes, known as pied-à-terres, and on flipped buildings to raise revenue and curb speculation.

At the same time, they urge lawmakers not to renew the 421a tax abatement for developers and owners, which “denies the city of New York nearly $2 billion a year in potential tax revenue, and thus constitutes the city’s single largest public expenditure on housing—more than the city spends on public or subsidized housing.” The program will remain a major issue heading into the next legislative session.

The authors propose changes to the existing property tax system, which they say puts “a significantly higher tax burden on many working-class homeowners than on the wealthy.” Low- and middle-income homeowners of color often pay three times the rate of wealthy, predominantly white brownstone, coop and condo owners, they write.

That kind of property tax reform has broad support. In a Daily News op-ed last month, Comptroller Brad Lander, a Democrat, and Council Minority Leader Joe Borelli, a Republican, outlined a similar plan for changing the property tax structure.

The CSS report also proposes creating a New York State Social Housing Development Authority to acquire vacant land and issue ground leases for social housing projects that include units for homeless New Yorkers.

And they call on the city and state to enforce tenant protections and create new ones, like an Open Books Law revealing building finances and unmasking the people behind opaque limited liability companies, and “Good Cause Eviction” legislation that would extend a version of rent stabilization rules to tenants in 1.6 million unregulated units.

The proposed Good Cause bill, another hotly contested issue before state lawmakers, would give tenants a right to a lease renewal in most cases so long as they pay rent and adhere to their leases. Landlord groups condemn the legislation as a form of universal rent control that makes it harder for them to raise rents to keep pace with costs or evict tenants.

The authors say such a reorientation will take time, money and cultural changes, but added that “we already spend a tremendous amount on sustaining the inequitable status quo in housing.” They cite the example of the $25 billion mortgage interest tax deduction, which gives wealthy owners a hefty break with no benefit to renters, homeless residents or even most low-income owners.

Such dramatic changes demand strong tenant organizing—the main theme of the report, said UNHP Research and Data Director Jacob Udell, one of the authors.

“The throughline is the importance of organizing,” Udell said. “People are already engaged as tenants in struggles to improve conditions. It’s meeting them where they’re at.”

One thought on “Rise of the ‘SHIMBY’? New Report Outlines Steps to Social Housing”

Social Housing is just another way of creating a NYCHA 2.0, the absolute last thing NYC needs.