The city’s affordable housing lotteries are notoriously competitive, but new data shows some progress: in the most recent fiscal year that ended in June, 6,173 applicants were approved for a unit through the lottery system, up nearly 24 percent from the fiscal year prior. But the approval process took longer for applicants than the year before, and the odds remain tough.

Adi Talwar

A Brooklyn apartment building with income-restricted units doled out through the city’s housing lottery.This story was produced by student reporters in the City Limits Accountability Reporting Initiative For Youth (CLARIFY).

After searching city housing lotteries for nearly 10 years, speaking to several politicians for help in her quest and being waitlisted for over 50 apartments in the midst of a local housing crisis, 33-year-old Gisele Santana is tired.

“I feel like I’m not being heard,” Santana, a single mother of two kids who works two jobs, said of her hunt for an affordable apartment in New York City, where rents have hit record highs in recent months.

She’s not alone. Since 2014, the city’s affordable housing lotteries have received tens of millions of applications from New Yorkers in search of housing, but just more than 29,000 people actually moved into new or rehabbed affordable homes via the lottery system between then and the end of 2021, city data shows.

“I don’t believe in luck, I believe in my hard work,” Santana said of the difficult odds.

The city’s affordable housing lotteries are notoriously competitive, but the city’s latest Mayor’s Manage Report shows some signs of progress: in the most recent fiscal year that ended in June, 6,173 applicants were approved for a unit through the lottery system, up nearly 24 percent from the year prior. The number of homeless households that moved into affordable apartments through lotteries also increased last year: More than 2,200, a record number of placements and up from 1,921 in fiscal year 2021, according to the city.

The uptick was because “more affordable units were created in prior years and recently made available for occupancy,” the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), which administers the lottery, said in its summary of the data.

But the lottery approval process also took longer last year, with a median time of 177 days, or around six months, for affordable projects to select and approve applicants for move-ins, up slightly from the year before. Less than a third of applicants who scored lottery units were approved within six months, the data shows.

| Performance indicators for the city’s affordable housing lottery by fiscal year | FY20 | FY21 | FY22 | ||

| Applicants approved for a new construction unit through the lottery | 5,559 | 4,993 | 6,173 | ||

| Homeless households moved into a newly constructed unit | 410 | 1,468 | 1,600 | ||

| Homeless households moved into a re-rental unit | 342 | 453 | 603 | ||

| Percent of lottery projects that completed applicant approvals within three months | 12% | 24% | 26% | ||

| Percent of lottery projects that completed applicant approvals within six months | 32% | 54% | 52% | ||

| Percent of lottery projects that took longer than two years to complete applicant approvals | 7% | 4% | NA | ||

| Median time to complete applicant approvals for a lottery project (days) | 246 | 168 | 177 | ||

| Percent of lottery units with applicants approved within three months | 46% | 56% | 32% | ||

| Percent of lottery units with applicants approved within six months | 70% | 73% | 51% | ||

| Percent of lottery units with applicants approved after two years | 1% | 2% | NA | ||

| Median time to approve an applicant for a lottery unit (days) | 104 | 88 | 176 | ||

| Median time to lease-up a homeless placement set-aside new construction unit (days) | 115 | 106 | 203 | ||

| Median time to lease-up a homeless placement voluntary new construction unit (days) | 210 | 215 | 214 |

HPD attributed the longer times to “lease-up process challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, and delays in advertising and approval processes following the launch of Housing Connect,” the new online portal for housing lottery applicants that the city launched in 2020, but which still needed “refinements and improvements,” more recently, the MMR says.

“HPD is committed to connecting households in need with affordable housing as quickly as possible,” the agency said in the report. “As the City continues to implement its goals of increasing efficient access to services and shaping government processes to prioritize the resident experience, HPD will be examining all additional factors affecting lease-up timing for lottery and homeless set-aside units.”

The city defines affordable housing as units in which rent costs one-third or less of a household’s income, with specific eligibility requirements based on Area Median Income (AMI) levels determined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

But as stated, such units aren’t easy to come by: According to The National Low Income Housing Coalition’s GAP report, New York State has just 84 units for every 100 households earning at or below 80 percent AMI ($106,720 for a family of four). The availability is even scarcer for residents in lower income brackets, their report shows.

HPD financed the creation of just 16,042 affordable units during fiscal year 2022, well below its target goal of 25,000 apartments and down steeply from the year before, when it financed 29,408 such homes, the MMR shows.

“Demand for these units is just so high in the city that the city has quite a way to go in terms of time change, to bring units online and add to the supply that’s needed,” said Hayley Raetz, director of data and policy at the NYU Furman Center.

In May, President Joe Biden announced the Housing Supply Action Plan, which aims to make affordable housing less expensive to produce through a number of mechanisms. It also encourages states and cities to use their COVID-19 relief funding on housing.

Gib Veconi, chair of Brooklyn’s Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Council (PHNDC), thinks the White House should be going even further to address the crisis. “Given the dire situation with housing nationwide, the federal government should turn to the idea of providing housing,” he said, saying the feds “can build housing where others can’t since they have more access as well as borrow at lower rates.”

Locally, some have called for New York State to revive some version of a recently-expired program called 421-a, which offered tax breaks to developers in exchange for their constructing a certain number of income-targeted units—what supporters say was a key tool to incentivizing and lowering the costs of affordable housing construction.

But critics of the controversial program argue it gave away too much in exchange for too little, and that many developers opted to provide “affordable” units to the highest-earning income brackets allowed under the program. According to the NYU Furman Center, developers shifted in the last five years to constructing more affordable units targeted to middle-income households then lower-income tenants.

Between 2017 and 2021, 8,500 apartments were built with 421-a tax abatements, but just 2,564 units were income-restricted, and about three-quarters of those were set aside for households earning 130 percent of AMI (the equivalent of $173,420 for a family of four), according to an analysis by the Community Service Society (a City Limits funder).

“Affordability is affordable to whom?” Veconi questioned. “What we should be trying to do is create the opportunity for people who live in New York City but are under displacement pressure for housing costs to find another place to live. That affordable housing should be accessible to those people under those rent burdens, who otherwise will be forced to leave the city.”

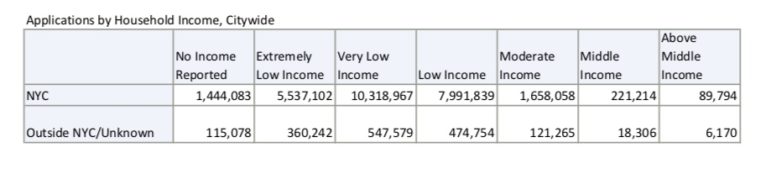

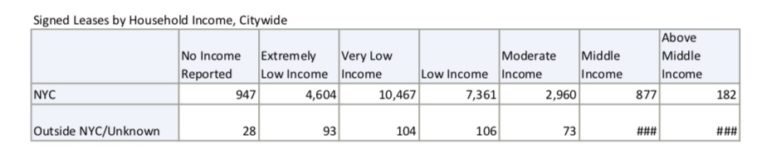

Between 2014 and 2021, leases signed for HPD lottery units were predominantly by households identified as “very low income” (10,467 such households) or “low income” (7,361), city data shows. But those income levels also saw the highest number of applicants, meaning they also face stiffer competition, as an earlier analysis by the news site THE CITY found.

Local Law 217 Report

Lottery applications by household income, 2014-2021

Local Law 217 Report

Leases signed for affordable lottery units, 2014-2021Santana, who has been trying her luck at the city’s housing lottery since 2013, says she frequently sees apartment listings she’s ineligible for because her salary is too low. In all the years she’s been applying, she said she’s never heard back about moving forward in the process—she’s only been rejected or waitlisted.

“A person like myself can’t just wait to be picked,” she said. “Something has to be set in motion for hard-working people.”

3 thoughts on “More People Snagged Units in NYC Housing Lotteries Last Year, But Wait Times Grew”

true not enough of low income units being built let alone none in any well off to do neighborhoods, wait list you will be waiting for years many cases over 6 to 8 years alot of bait and switch like the atlantic yards pacific park apartments, majority of those units are high end middle and market rate units and it supposed to be affordable,really? and most of our elected officials stand back and stand by, sounds familiar ? more homeless more evections, a dam shame , but a got a tip for you all, stop voting these brought elected officials in office, until then nothing will get better with this nyc unaffordable housing crisis

I searched Housing Connect for apartments at the 130% AMI level in 2020 and 2021. I received several invitations to apply for units but declined because they were more than I wanted to pay, given the location, unit size and quality of construction, often with luxury amenities I didn’t want. I can find housing in Brooklyn at 15-20% of my income, not the 30% of income targeted by HPD programs. That’s all fine with me, as long as someone else fills out that tier of the rental structure to make it work.

I am still waiting I put in 11 applications for housing lottery connect since January 2022 am looking for senior affordable housing everything is a waiting list