Residents in upstate New York are putting a new statewide constitutional right to its first test in two lawsuits filed this spring, alleging that a landfill receiving garbage from the city is disrupting their right to clean air and a healthful environment.

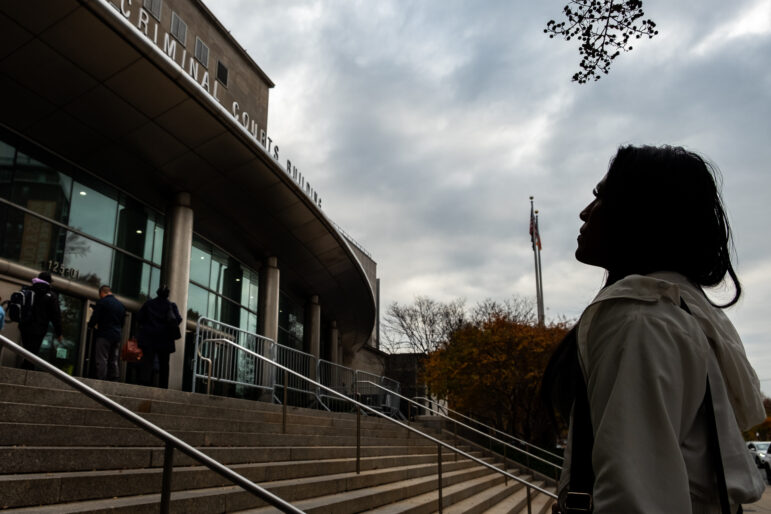

Adi Talwar

Trash bags waiting to be collected on Reservoir Oval West in The Bronx. The borough’s trash gets transported to a landfill in Perinton, NY, where residents are suing over the stench.Residents in upstate New York are putting a new state constitutional right to the test in two lawsuits filed this spring, alleging that a landfill receiving garbage from the city is disrupting their right to clean air and a healthful environment.

The lawsuits are the first to cite the “right to clean air and water, and a healthful environment,” which New York voters approved to add to the state constitution at the polls last November, according to the plaintiffs’ lawyer, Linda Shaw.

Both cases were filed by the same plaintiffs under the organization Fresh Air for the East Side, Inc., who reside in Perinton and surrounding towns about 300 miles north of New York City, where a portion of the city’s garbage is delivered via rail. For nearly five years, the group has been complaining about an increase in odor emanating from High Acres Landfill and Recycling Center, which sits on the border of Perinton and nearby Macedon.

One complaint names New York State, New York City, the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), and the landfill’s operator, Waste Management of New York, as defendants; the other names the town of Perinton, the town’s zoning board of appeals and Waste Management.

The plaintiffs’ “lives and properties have been and continue to be adversely impacted by persistent, noxious, offensive Odors and Fugitive Emissions being released from the Landfill,” the complaint reads.

Many of the more than 200 residents included in the lawsuit are complaining of nausea, headaches and stress, says Shaw, who is claiming the odors have resulted in a loss in quality of life. “It creates a significant amount of anger in these human beings because they walk outside and it’s disgusting,” she told City Limits.

New York City’s garbage is transferred to various landfills and waste conversion facilities in multiple states. High Acres receives waste from The Bronx, Queens and Brooklyn, according to the city’s Department of Sanitation. Brooklyn waste is also sent to a landfill in Virginia, while Staten Island garbage is deposited in South Carolina. The city also sends a portion of waste to facilities in the Northeast that convert it into energy.

| Garbage from: | Ends up in: |

| Staten Island | Lee County Landfill in Bishopville, South Carolina |

| Brooklyn | High Acres Landfill in Perinton, NY, and the Atlantic and Amelia Landfills in Virginia |

| Queens | Waste-to-energy facilities in Niagara, NY, and Delaware Valley, PA |

| Manhattan Community Boards 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 10 and 12 | A waste-to-energy facility in Newark, NJ |

| Manhattan Community Boards 5, 6, 8 and 11 | Waste-to-energy facilities in Niagara, NY, and Delaware Valley PA. |

| Bronx | High Acres Landfill in Perinton, NY |

Waste Management of New York, which runs the landfill, could offer only limited comment due to the pending litigation, but said that the facility operates in full compliance with regulatory requirements. “The High Acres facility has been a proud partner in the region for 50 years, providing numerous economic and environmental benefits,” a spokesperson told City Limits.

In 2015, the landfill began accepting garbage from New York City via rail—a means of transporting waste that is intended to reduce truck traffic and associated emissions. The method has largely gotten the support of legislators seeking to reduce the environmental impact of waste transfer facilities historically situated in environmental justice communities. In 2018, the city passed the Waste Equity Law, which reduces the capacity for waste transfer stations located in four overburdened community districts, but which included exemptions for facilities that transport garbage using trains rather than trucks.

But as seen in Perinton and the surrounding towns, the method can have a negative impact on the other end of the line. Garbage often sits in the sealed railroad cars for days on end, leading to a worse odor when it’s finally emptied into the landfill, explained Shaw. The DEC confirmed that it does not have oversight of how long the garbage sits in the cars.

Adi Talwar

April 5, 2022: Corner of East 135th Street and Park Avenue in Manhattan

“We’re not saying New York City garbage is stinkier than anybody else’s, it’s just that because it cooks in these railroad cars that are sealed,” she said. “So when they open those railroad cars, it’s terrible.”

A spokesperson for Waste Management noted that two studies conducted by DEC, the town of Perinton and Waste Management in 2019 and 2020 found no difference between rail and trailer deliveries.

In December, Perinton Town Supervisor Ciaran Hanna announced a new five-year host community agreement aimed at reducing odor from the landfill. Among the measures was to limit the age of waste disposed of there to no more than seven days from transfer facility to the landfill. It also reduced the capacity of highly odorous waste—biosolids, a byproduct of the wastewater treatment process—by half, and stipulated that only 50 percent of all trash dropped at the landfill can be from New York City. In 2020, 90 percent of the landfill’s capacity was from the five boroughs, the complaint shows. That reflects an increase of 284,392 tons of garbage from New York City in 2015 to 646,744 tons five years later.

The issue has also not gone unnoticed by the DEC, which has intervened multiple times. In September 2020, DEC Commissioner Basil Seggos wrote a letter to the district manager of Waste Management, Jeffrey Richardson, noting that odor complaints related to the landfill had “increased markedly” that month and that operational issues at the landfill, including insufficient use of misting systems that help tamp down the smell, were contributing to the problem.

“New York State’s top priority is ensuring that area residents are not exposed to any potential site-related health or safety hazards,” a spokesperson for the agency told City Limits. “DEC rigorously oversees all operations at the WM facility and responds to community concerns about odors. In addition, DEC works with WM to minimize odors and implement air monitoring.”

Between 2021 and 2022, the DEC authorized the facility to add a geomembrane cover over nearly 12 acres of the site to reduce odor. The company will add a cover over an additional 20 acres later this year, the DEC said.

The agency has taken several other measures this year to intervene, including partnering with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to monitor air quality in real time with a specialized vehicle. The screening tool found no health or safety concerns but did find methane levels to be above the reporting limit, according to the agency.

Methane, a common byproduct of waste facilities, is more than 25 times more powerful in contributing to global warming than carbon dioxide, according to the EPA.

The lawsuits allege that emissions associated with the landfill also violate the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, statewide legislation aimed at reducing emissions, arguing there are practical ways for the state agency and site operator to reduce the volume of gasses escaping the facility.

“What we’re asking for not only under this new green amendment, but also under the new Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, [is] that they do what they’re supposed to do,” said Shaw. “It’s not being managed properly.”

Liz Donovan is a Report for American corps member.