New York should take page from cities like San Francisco, the report says, which launched the Financial Justice Project to eliminate or overhaul government-imposed monetary fees that disproportionately burden low-income residents, and people of color.

Adi Talwar

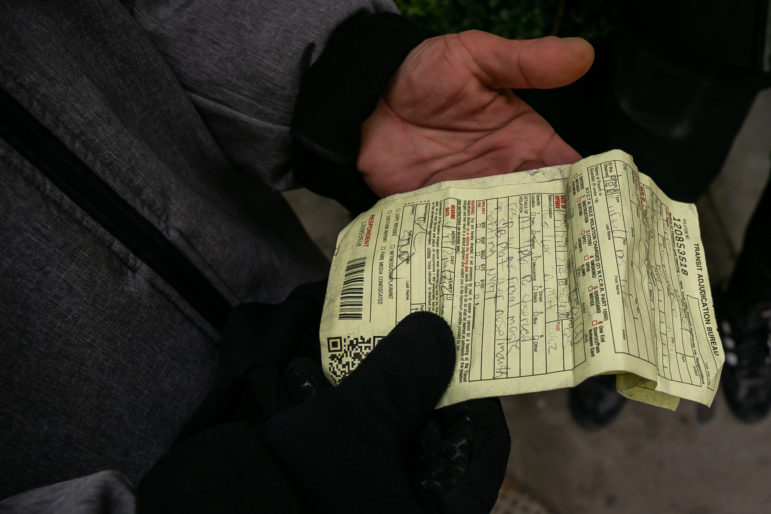

A summons received by a New Yorker experiencing homelessness, for not wearing a mask in a subway station.In New York City, jumping the subway turnstile can earn you a $100 fine. Small businesses that fail to properly display their refund policy can face anywhere from a $50 to $500 violation. Transferring money to someone being held in one of the city’s jails comes with a surcharge of up to $11.95 per transaction—money that goes not into the city’s coffers but to the private company that runs the payment system.

These are just a few of the myriad government-imposed fines, fees and forfeitures that New Yorkers pay, accounting for $2 billion a year, according to a report released Thursday by the Center for an Urban Future. The policy analysis recommends that New York take a page from cities like San Francisco, which launched an initiative in 2016 to eliminate or overhaul such monetary fees that disproportionately burden low-income residents, and people of color.

“There are fines and fees on the books today that are important sources of revenue for the city or are legitimately designed to deter bad behavior,” said Eli Dvorkin, the center’s editorial and policy director who co-authored the report. “But the reality is that there’s so many of these fines or fees that aren’t well thought through, or where the impact of them is unjust.”

San Francisco launched its Financial Justice Project (FJP) in 2016, inspired by an earlier U.S. Justice Department report, produced in the wake of the police shooting of Michael Brown, which revealed how the city of Ferguson, Missouri, unlawfully imposed tickets and fines on Black residents as a means to raise revenue.

Since its launch, San Francisco’s FJP has overhauled dozens of the city’s fees and fines after examining how they were issued, and who was most impacted. “We looked at what happened when people couldn’t pay,” Anne Stuhldreher, San Francisco’s director of financial justice, told the Center for an Urban Future. “Their credit score can be impacted. Their license can be suspended, not for dangerous driving, but because they simply couldn’t pay their bill.”

San Francisco’s reforms included eliminating water shutoff fees and waiving millions in criminal justice debt, creating a pilot program for parents who’d fallen behind on child support payments and allowing low-income residents to access payment plans for parking violations.

“That program has been phenomenally successful in moving what otherwise can be a very slow and cumbersome municipal bureaucracy toward delivering real results in identifying—and actually eliminating and reforming—fines and fees that have a disproportionately harmful effect on low-income residents,” Dvorkin told City Limits. “There’s a huge opportunity to do something similar here in New York.”

New York has so far made piecemeal efforts to reform its labyrinthine system of fines: In January, Mayor Eric Adams ordered six city agencies to review regulations that result in monetary penalties for small businesses, and to identify those that should be eliminated or replaced with warnings. In 2019, the city ceased charging people in jail for making phone calls. And last year, New York State stopped suspending driver’s licenses over traffic debt, allowing New Yorkers who can’t afford their tickets to apply for a payment plan.

But the city could take things further by setting up a program similar to San Francisco’s FJP, which could review the charges imposed on residents across various government systems, identifying those that are inequitably enforced, and push for changes on the state level when needed, Dvorkin said.

He pointed to “low-hanging fruit” such as mandatory court surcharges, which disproportionately impact Black and Latino New Yorkers who are more likely to be involved in the criminal legal system. New York courts collect millions each year in such payments from people convicted of even non-felony crimes; residents on parole are also required to pay a $30 supervision fee each month (lawmakers in Albany are currently weighing a bill, the End Predatory Court Fees Act, which would eliminate these charges).

“That to me is just that is an example of really kicking folks when you’re down,” said Dvorkin. “That is so counterproductive to the goal of helping folks re-enter their communities successfully.”

Fines that are targeted for reform could be eliminated entirely, replaced by non-monetary penalties like participation in a community service program, or reconfigured on a sliding-scale so fees are based on what the recipient can afford.

“The fact that you receive the same ticket, the same dollar amount, whether the vehicle being ticketed is a luxury SUV that costs over $100,000 or a moped parked in Brownsville…that starts to suggest the opportunity to rethink that system a little bit,” Dvorkin said.

The goal is not to stop the city from collecting revenue via fines, he added, but to create a system “that really does take into account the impact of that fine on somebody’s life.”

It can be difficult to assess what impact these types changes have on overall revenue collection for cities, since New York and many other municipalities don’t collect comprehensive data on the costs of administering and collecting fines and fees, Dvorkin said. A 2019 report from the Brennan Center for Justice that looked at criminal court fees nationwide found they were “ineffective at raising revenue,” pointing to one county in New Mexico, for example, that was spending $1.17 to collect every dollar of fine revenue it raked in.

So far, the changes made by San Francisco’s FJP “have been pretty revenue neutral,” Dvorkin said. His report recommends New York City adopt a similar initiative that could run by the city comptroller’s office, with “leadership and buy-in from top level elected officials,” including the mayor’s office and City Council.

“The key to San Francisco’s success with their Financial Justice Project was embedding it directly in government,” Dvorkin said. “If this was a situation where individual agencies were asked but not mandated to reform themselves, I don’t think San Francisco would have had the success that that they’ve had.

Overall, he argues, the city should look at potential fine reforms as another tool in its toolkit for equity. “There’s so much that city government can do to help expand economic opportunity,” he said. “One other option for policymakers is to simply help keep more money in the pockets of low-income New Yorkers. And that’s what this idea is all about.”