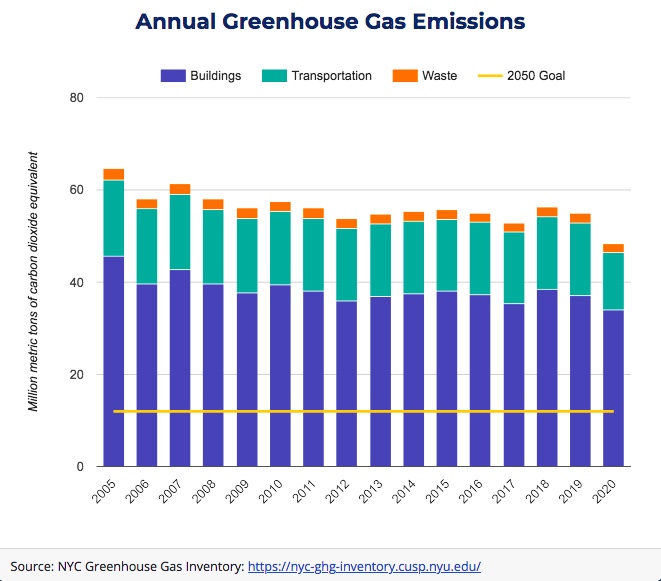

By 2050, the city’s annual greenhouse gas emissions should be no higher than 12 million metric tons of carbon dioxide—in 2020, buildings alone accounted for 34 million metric tons. “It kind of paints a very stark picture of how much work we have to do and how it can’t just be business as usual.”

Adi Talwar

Friday evening traffic heading West on 42nd Street between 5th and 6th Avenues in Manhattan.Lea la versión en español aquí

New York City’s air quality is improving, but the metro area remains one of smoggiest cities in the country, according to a report released Thursday by the American Lung Association. The new data comes as city officials and advocates clash over how to enforce a groundbreaking law to crack down on emissions from buildings, the biggest sources of pollution.

New York took 14th place for “Cities Most Polluted by Ozone”—the only metro area in the Northeast to make the top 25, according to the report. That finding is in spite of the city having fewer high-smog days during the period the report examined, 2018 through 2020, than the two years prior.

After measuring the number of days with unhealthy ozone levels, the Association gave “failing” grades to The Bronx, Manhattan and Queens, the report notes. (Data for Brooklyn was insufficient to grade.) Ozone pollution is linked to vehicles and fossil fuels burning in buildings and power plants.

“We’re really concerned about transportation and building pollution,” said Trevor Summerfield, director of advocacy for the American Lung Association in New York. “That type of pollution often harms communities of color and disadvantaged communities that are bearing the burden of pollution.”

The report also measured particle pollution, a byproduct from the burning of fossil fuels or wood. More frequent wildfires, which the United Nations Environment Programme named as a top global threat earlier this year, have led to increased levels of particle pollution in western states—but they’ve also impacted air quality in the Northeast.

“It’s almost like a blanket,” said Summerfield. “Even though we’re so far removed and think that we’re not getting that type of pollution, it travels.”

That said, the metro area’s particle pollution, also known as soot, did improve markedly — last year, the New York-Newark region was tied for the 20th worst city for particle pollution, and this year, it has moved to the 75th spot. Upstate cities, including Albany and Buffalo, saw worsening levels of particle pollution.

To decrease both types of contaminants, there needs to be a focus on reducing building and vehicle emissions both statewide and regionally, Summerfield notes.

The city still has a long way to go to meet its own environmental goals: On Monday, the comptroller’s office launched a dashboard showing where the city stands in relation to its target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent over the next three decades.

The NYC Climate Dashboard, which visualizes data through 2020, shows that although emissions have decreased over the past decade and a half, levels of carbon dioxide are still far above what they would need to be in the next 30 years to meet that goal. By 2050, the city’s annual greenhouse gas emissions should be no higher than 12 million metric tons of carbon dioxide—in 2020, buildings alone accounted for 34 million metric tons.

“It kind of paints a very stark picture of how much work we have to do and how it can’t just be business as usual to get that level of ambition accomplished,” Louise Yeung, chief climate officer for the comptroller, told City Limits.

Buildings are the top polluter, the dashboard shows, with residential buildings emitting nearly 10 million metric tons of carbon dioxide from natural gas.

These findings come as elected officials and advocates put pressure on Mayor Eric Adams to commit to enforcing Local Law 97, which requires buildings over 25,000 square feet to lower emissions beginning in 2024, reaching a reduction of 40 percent in 2030 and 80 percent in 2050.

The ambitious law passed in 2019, but some environmental advocates and elected officials have expressed concern about how it will be enforced, including whether building owners will be charged the civil penalties written into the law, which would hit violators with fees based on how much their buildings’ emissions exceed the city’s benchmarks.

Other officials argue the focus should be on educating and encouraging owners to come into compliance, rather than aggressive fining, as meeting the new standards will require many building owners to retrofit their properties with energy efficient features.

“We will not hesitate to levy penalties on buildings that do not comply,” Rohit Aggarwala, the city’s chief climate officer and commissioner of the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), said during a more than four-hour City Council committee meeting last week on oversight of the legislation. But there needs to be leniency as building owners make the transition, he added. “We need to understand the challenge of building space and undertaking the work that needs to be done, and we need to do everything we can to help them,” he said.

Punishing building owners who are struggling to get into compliance would be counter-productive, Aggarwala argued. “We have no intention of giving anyone a free pass or letting anyone off of the hook,” he said. “But we also see no benefit to the environment in front of someone who is genuinely doing everything.”

Environmental groups, however, say penalties are necessary to the law’s effectiveness.

“There’s now over a decade of evidence from all across the country: building owners by and large won’t implement energy efficiency projects even if those projects save them money and they’re given helpful resources, even grants,” wrote Pete Sikora of New York Communities for Change, in a testimony. “The government has to set and enforce requirements.”

Previous efforts to decarbonize the city’s buildings and switch to cleaner energy have begun to make improvements in air quality, another study published in December suggests. Researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and Drexel University found that a citywide ban on heavily-polluting heating oil #6 led to decreased pollutants from 2012 to 2016, when the transition off of that oil began to when the ban was fully instituted.

It’s not just up to New York, though. Summerfield notes that for pollution levels to decrease significantly, more states need to take aggressive action in reducing emissions.

“Hopefully over the coming years we’re going to see the fruits of our labor that we’ve worked so hard on to get some of these advancements in climate and energy policy in the state moving forward,” he said. “But this is a regional issue and national issue as well. Everybody’s got to commit to this.”

Liz Donovan is a Report for America Corps Member.