“In the city’s hands for almost three decades, the vacant, landmarked Kingsbridge Armory—the world’s largest, built in 1917 for the National Guard—is still empty, despite a deal seemingly sealed in 2012.”

Jordan Moss

The 500,000-square-foot Armory on Kingsbridge Road, which has been in the hands of the city—albeit empty—since 1993.It’s a shock.

It shouldn’t be. The Bronx has plenty of experience getting screwed. But it’s shocking nonetheless.

In the city’s hands for almost three decades, the vacant, landmarked Kingsbridge Armory—the world’s largest, built in 1917 for the National Guard—is still empty, despite a deal seemingly sealed in 2012.

After being told by the state in 1993 that it would soon have control of the immense structure—over 500,000 square feet on Kingsbridge Road—it took the city 19 years to come up with a viable plan and get it approved by the City Council. But things were finally looking good. Despite exasperating fits and starts, there did seem to be a solid plan in 2012 to transform the Armory into nine ice hockey rinks and 50,000-square-feet of space for community nonprofits. Supporting a living wage and the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition’s (NWBCCC) push for community use, the Kingsbridge National Ice Center (KNIC), an amalgam of companies with hockey legend Mark Messier at the forefront, was the victor. It came with a sense of relief and accomplishment all around.

But in the last decade, KNIC has done nothing with the mammoth edifice and most of its work has been in court, in battles with three of their partners and the city’s Economic Development Corporation (EDC), the overseer of everything involved. In 2016, four years after its deal with the city, KNIC was unable to acquire the necessary escrow from EDC to proceed with its $350 million project because it hadn’t gathered the needed capital, according to the development corporation. (KNIC has disputed this in court papers, accusing the EDC of instituting the escrow condition as a means to deliberately delay the project, and claiming they’d satisfied their financial obligations, in part through a promised multi-million dollar loan from the state).

The litigation continued until last fall, when a state court ruled against KNIC. In a statement, the EDC says the court concluded “that KNIC did not provide the necessary evidence of financing for the ice center project at Kingsbridge Armory by the required deadline in 2016. Therefore, the project will not be proceeding. We are disappointed that KNIC has been unable to realize the financing for the project, despite continued efforts since the 2016 deadline.”

Kevin Parker, of KNIC, declined to comment on the record about the specifics of the litigation, but told City Limits he’s now in discussions to bring the ice center project to New Jersey instead.

That leaves The Bronx with a still-empty Armory. It’s worth it to take a look further back at what else went wrong—and right—in order to help us do things differently, so the massive public site can be utilized relatively soon.

I wrote my first article about the Armory in November 1993 for the Norwood News (a Bronx nonprofit community newspaper I became editor of the following year) when the state, no longer needing it for the National Guard, handed it over to the city. There was a lot to report on. At the time, the superintendent of the desperately overcrowded school District 10 wanted the Armory to be home to new schools, while then-Assemblyman Oliver Koppell preferred it to be an amateur athletic facility and secured a $100,000 grant for the Bronx Overall Economic Development Corporation to study that possibility. But that agency never completed the report, so it returned the funding. In 1998, the NWBCCC began collaborating with the Pratt Institute, which resulted in architectural drawings that included three 800-seat schools inside the Armory, a sports complex, a bookstore, a community center and more. Their efforts after that were relentless.

READ MORE: Bronx Group’s New Path: Not Fighting Power, Taking It

But in 1999, the Giuliani administration formed an Armory task force of nine agencies, from which local residents and Bronx elected officials were excluded. And the next year, the mayor released a plan for a retail/entertainment center with RD Management, but no schools were in it. RD eventually backed out due to the construction cost. In 2003, with Mayor Michael Bloomberg in office, a national developer, the Richman Group, picked up NWBCCC’s proposal and later that year the EDC announced it would release an RFP (request for proposals). But because of political infighting among Bronx Democrats, an RFP wasn’t released until late 2006. (Schools were eventually deemed a non-starter for the site, thanks to landmark rules that don’t allow exterior alterations.)

In 2009, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced a deal with the Related Companies to fill the cavernous structure with a giant mall. But because Related wouldn’t promise to pay its workers a living wage—$10 an hour at the time—the NWBCCC organized with retail and construction unions to defeat the plan. The City Council ditched it 45 to 1.

Bloomberg and the EDC issued another RFP, and this time the agency’s pick of KNIC got the support it needed from the Kingsbridge Armory Redevelopment Alliance (KARA), a group of stakeholders led by the Coalition—because KNIC agreed to a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA). In addition to 50,000 square feet for community needs and a living wage for workers, KNIC agreed to open the ice rinks for the public at a cost of $1 million a year.

But it’s been a decade since Bloomberg and KNIC officials celebrated that deal at the Armory’s massive drill hall. There was pretty much no sign that Mayor Bill de Blasio was working to move things along, maybe because KNIC didn’t secure the loans it needed while keeping the EDC in court. I wish the news entities all over the city had been paying closer attention. (I know coverage matters, because the Norwood News’ relentless coverage of this drew attention in our northwest Bronx area and sometimes beyond. More low-income neighborhoods would benefit from more nonprofit newspapers, but that’s another story.)

“Unfortunately, the KNIC developer turned out to be a snake oil salesman who could not be upfront about his financial reality, even when given countless opportunities to do so,” said State Senator Gustavo Rivera (D), who represents the district, in an email to me. “The Bronx has lost many years of utilizing our monumental asset due to the apparent lack of honesty, transparency, and professionalism of a developer who over-promised and under-delivered.”

Back when the city announced the first RFP in 2006, the Norwood News stopped the ‘Armory Clock,’ which we had published in every issue since July 2005, marking the number of days that had passed since Gov. George Pataki’s visit to the Armory, where he pledged to work with local officials to make something happen. I think we all need to turn that clock on again, beginning at 5,963 days (I added it all up from Oct. 5, 2006, when we prematurely announced the clock’s retirement) and keep it going until the first day we Bronxites can walk in the front door, get some coffee, see a movie, get to work or experience whatever the heck we created there. That would be a true community benefit, unlike the formal one that went nowhere.

As Neil deMause reported in City Limits last month, many CBAs have been ineffective or unenforceable, sometimes by design. But if it weren’t for KNIC’s inability to secure funding, the CBA for the Armory would have likely been an unusually successful one. It was clearly designed to be enforceable by the community, not by elected officials, like those who failed to enforce the Yankee Stadium CBA.

READ MORE: What Ever Happened to CBAs? The Rise and Fall of ‘Community Benefits Agreements’ in NYC

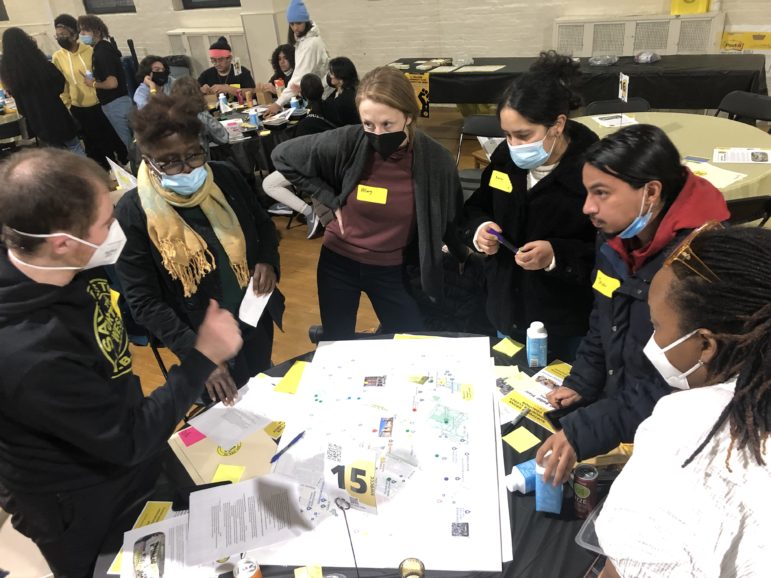

NWBCCC knows this all too well. Ice rinks were not their vision for the Armory, but they actively supported it because they and KARA—not political leaders—negotiated the CBA. Having learned from many years organizing around the Armory, the group used its annual meeting last month to draw on that history, and brainstorm new visions of what the structure’s internal transformation can provide.

Jordan Moss

At the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition’s annual meeting last month, attendees brainstormed ideas for what should fill the Armory.“What if we owned it?” said Sandra Lobo, the NWBCCC’s executive director, referring to, yes, the Armory. “The community [should be] at the lead of creating governance and accountability because they’re the ones that own the land under the building.” To determine how that could work, the Coalition has begun working with Urban Design Forum and the Van Alen Institute to come up with new ideas suitable to the neighborhoods surrounding the Armory.

Rivera already strongly supports NWBCCC and local stakeholders efforts to “ensure the new chapter of reviving this landmark [as] an emblem for community ownership, participatory ownership and mutual benefit.”

I remember that in 1995, Norwood resident Ronn Jordan, frustrated with the overcrowded school his kindergartner son attended, got involved with NWBCCC to pressure the city’s School Construction Authority to finish its delayed construction of P.S. 20 and to add even more new schools to its to-do list. Soon after, he became a leader in demanding schools at the Armory. Jordan still has big ideas, like the Armory being home to an NYPD Community Policing Training Center that partners with at-risk youth.

The fact that he’s still thinking about it is an accomplishment in and of itself.

Chris Jordan, that kindergartner, is now 30, and the dad of Ronn Jordan’s first grandchild, Charlotte, who is 8.

If that’s not a clear message that the leadership and process of envisioning and creating the Armory’s next existence needs to change drastically, I don’t know what is.

Jordan Moss is a Bronx resident and former editor of the Norwood News, where he covered the development of the Kingsbridge Armory for more than a decade.

14 thoughts on “Opinion: The Kingsbridge Armory Plan Fell Apart—Again. The Bronx Deserves Better Next Time”

Department of corrections needs a new academy. Seems like a decent location.

Its a shame put s rinnk there from brian sten section 1 off ice official in playland

Fascinating. How about a concert hall?

It sad to here that the kingsbride armory which was built in 1917 such a beautiful building. Has been close for three decades. This building could bring hope and new jobs to the bronx community. And after all the proposals that’s been on the table, to open up the kingsbride Armory. It still remains close. As a born native of the bronx, it saddens me to here this news. Thank you signed Angel Nieves

It needs to be for the whole community to enjoy not only some. An investigation on who benefited and misused our tax money needs to take place for The Kingsbridge Armory and the skate ring at Vancortland park which only opened for one year after so much money was spend on it and then more money to remove it. Who got out tax money? somebody needs to be help responsible.

Fordham U – consider selling the Lincoln center building and move their law and/or re-establish medical schools. Another idea, team up to open STEM program along the lines of Technion Cornell on Roosevelt Island or NJIT and Ben Gurion U.

Walked past it last night thinking “It’s such a shame this beautiful building is empty”

Every inch of land is being used to build high rise apartment buildings, but no community center or parks to help families in need. This allows predators to groom the preteens bcuz parents don’t have anywhere to enjoy family time, nor sport programs to teach their children life filled with integrity, confidence, etc. Allow them to realize that their choices now will shape the future for all of us. We need help now, or as we see is happening now, we will lose an entire generation bcuz no one cared about the quality of life we refused to fight for.

Please make this an indoor multi-sport center, it’s huge.

Soccer, hockey, basketball, velodrome, running track, rock wall, parkour, etc.

This is the answer and would be massively popular. Make it modular so spaces could be modified for certain events if there is more demand for a particular sport. For example, a hockey rink that transforms for basketball.

Not surprised at all. As long as the Bronx keeps electing incompetent leaders nothing will get done. Example Assemblyman Rivera hasn’t sponsored legislation in over a decade. Senator Rivera has no say in this matter. The Armory’s future will be determined almost exclusively by the newly elected Councilwoman Sanchez.

Bring back the Guard units that were there. There were 4 Battalion sized units there that were dispersed throughout the city and state. Close the smaller armory’s and utilize the biggest. The men spend money while drilling there.

Yes!! a community YMCA that services the youth, Swim classes dance, classes, art classes a gym for the youth for basketball. Seniors Could also benefit aquatic swimming exercise classes such a Zumba class yoga, dances classes Pilate classes and an in door track within the facility simply because seniors do not feel safe walking around the community due to increase in crime the community where

Also, because more apartments buildings are Being developed there is no place to park in this community.

I lived in this community 39 years and I watch all different opinions about what to build there yet nothing has been done. I pray that with this office the senators councilman Government and city officials to really do something with this Armory Building, because as it stands right now used clothing is being hang sold outside on the gates of this building it looks like a flea market.

I walk by this area everyday and always notice the litter that surrounds it. I have just been living in the Bronx for 2 years and I heard that this has been closed for 30years? Seems that ever since it was closed, nobody is taking responsibility to maintain it. What a waste! It looks like a haunted building.

LET TRUMP DEVELOP THE SITE INTO A MASSIVE HOTEL LIKE – SMALL SIZE APARTMENTS FOR POOR PEOPLE.

YES AFFORDABLE HOUSING !!

ANYONE OPPOSING THIS MUST BE PUBLICLY CASTIGATED !