The pandemic worsened the hunger crisis for many New Yorkers, though more severe impacts were staved off by COVID relief programs. But need is expected to rise again, as government benefits expire and the state’s eviction moratorium ends in January.

City Harvest

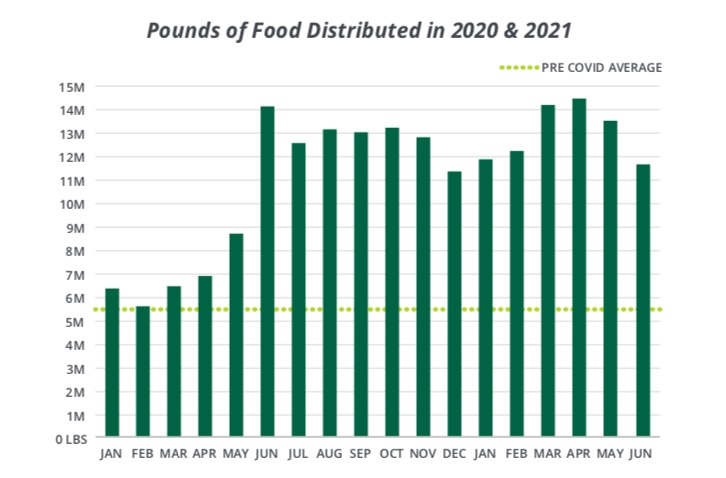

City Harvest workers.In June of 2020, when New York City was just a few months into the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated lockdowns, City Harvest—a nonprofit that distributes surplus groceries to soup kitchens and food pantries across the five boroughs—doled out more than 14 million pounds of food in one month alone, nearly three times that of its usual, pre-pandemic average.

More than a year later, that heightened demand for food donations hasn’t let up, according to the organization, which has distributed more than 11 million pounds of food every month since, according to a new report; before the crisis, they averaged just around 5.5 million pounds monthly.

Of the 1 billion pounds of food City Harvest has delivered since its founding in 1982—a milestone it surpassed in September—220 million alone was distributed in the months since the pandemic began.

What’s more, the anti-hunger group, which in pre-pandemic times relied almost entirely on food donated by farms and restaurants, has been purchasing its own food as well as part of its “disaster feeding plan”—typically only triggered during shorter term emergencies, like Hurricane Sandy, but which has been consistently in effect since March 2020, according to executive director Jilly Stephens.

“We started buying food on March 9 last year, and we haven’t stopped,” said Stephens. “When we’re not in a disaster response, which thankfully doesn’t happen every year until now, we only spend about $200,000 [annually] on food. Last year, we spent close to $20 million.”

These numbers, she says, illustrate the stubborn persistence of food insecurity, which lingers long after an economic crisis moves out of the headlines. The surge in food insecure households spurred by 2008’s Great Recession, for instance, didn’t subside to pre-recession levels for a decade.

City Harvest

Pounds of food distributed by City Harvest in 2020 and 2021.“Then overnight, all the gains that we made over those 10 years to get down to the levels that we saw before, were wiped away with the pandemic,” Stephens said. “For many New Yorkers, it’s a very long, slow-rising recovery.”

The city’s unemployment rate was 8.4 percent in October, according to state Department of Labor data, significantly lower than during the height of the pandemic in 2020, when it peaked at 20 percent, but still well above pre-pandemic levels .

Experts say the hunger crisis could have been worse were it not for the number of government benefit and relief programs rolled out in response to the COVID crisis, including extra Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP benefits (formerly known as food stamps), stimulus payments and the enhanced Child Tax Credit (CTC).

The number of people in the New York City metro area unable to afford enough food peaked at 6.219 million in May of 2020, according to a November report from the organization Hunger Free America, based on U.S. Census Household Pulse data. But that figure dropped to 3.425 million by August of this year, a decrease the report attributes to the “massive boost in federal food and cash aid.”

During that period, federal spending on SNAP in New York City alone almost doubled, the same report notes, from $288 to $428 million. “The federal government’s expanded food and cash aid was the key factor in preventing mass starvation during the height of the pandemic,” Hunger Free America CEO Joel Berg said in a note accompanying the report.

But hunger levels could rise again, experts warn, as government benefit programs expire. Enhanced federal unemployment payments offered to out-of-work Americans during the pandemic ended in September, while expanded monthly Child Income Tax Credits could run out at the end of this month unless Congress acts to extend it by passing President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better bill.

Locally, New York’s current eviction moratorium is slated to expire on Jan. 15, removing protections that have kept tens of thousands of renters in their homes.

“Food is often viewed as an elastic expense in the household. You have to pay your transportation, your rent, your utilities,” said Stephens, meaning people are often likely to make sacrifices when it comes to their grocery budgets. The rising cost of food, thanks to ongoing supply chain issues, is another contributing factor. “That scarce food dollar that they have isn’t going to go as far as it did before.”

City Harvest is already planning for future anticipated need. They expect they’ll need to secure and deliver an additional 33 million pounds of food for each of the next three fiscal years, on top of the 75 million pounds annually they’d already planned for.

“The lines are still long,” Stephens said. “People still need help.”

One thought on “Heightened Food Insecurity in NYC Likely to Persist Long After Pandemic Wanes, Experts Say”

Ceo Renee Mitchell of Breaking The Cycle Drop Corp. Says United States is one of the richest country in the world. There is no reason why they should be a food shortage. Maybe if the government increase livable income and make it more affordable and provide better resource we won’t have these problems.