The Bronx is home to the fewest miles of Open Streets, and only 16 percent of those that are included in the city initiative are considered operational—or barricaded off to prevent cars—a new survey from Transportation Alternatives found.

Jeanmarie Evelly

An Open Street in Astoria, Queens at the start of the pandemic in 2020.During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, as lockdown measures relegated many New Yorkers to the stuffy confines of their apartments, the city turned to its streets for more social distancing space. After a rocky start, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced in March that the Open Streets initiative—which turns certain roadways into pedestrian-only spaces during set times, blocking them off to most car traffic—would be permanent, calling the program “a runaway success.”

A new survey of the city program, however, found a number of equity and logistical issues, including that the best-functioning Open Streets tend to be located in or near wealthier neighborhoods. Of the 274 roadways on the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) list of participating streets, fewer than half, or 126, were found to be actually operational—with barriers in place blocking them to cars—during their designated hours, according to visits advocacy group Transportation Alternatives (TA) made to all the sites this summer.

“People feel that Open Streets are more inviting when cars do not intrude on the Open Street and when barricades protect the Open Street,” the report reads. “When drivers drive down these barricade-less streets, it sends a message that they are free to drive down all Open Streets.”

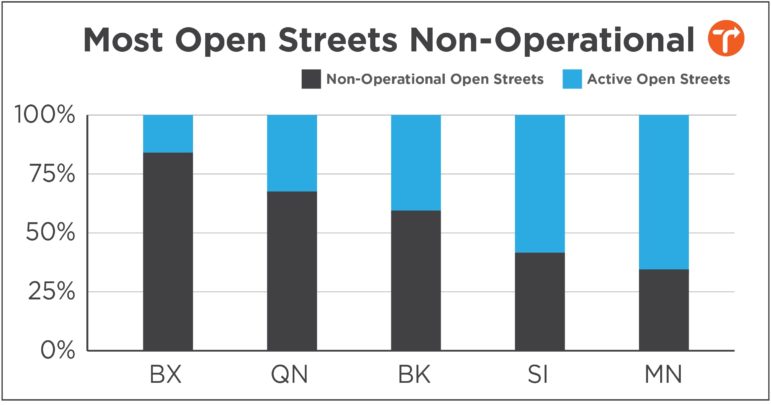

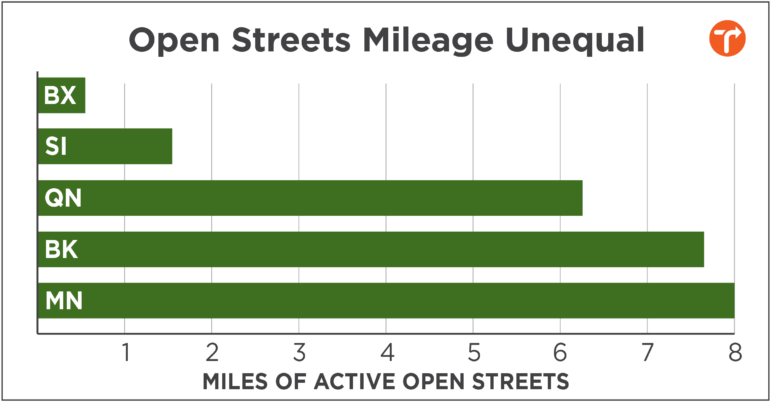

The group’s survey found the greatest issues in The Bronx, where 84 percent of listed Open Streets were found to lack barriers during TA’s visits, compared to 34 percent of those in Manhattan that did (Manhattan has the most Open Streets overall, with 102 to The Bronx’s 31. Staten Island has just nine). The Bronx is also home to the fewest miles of Open Streets, and the borough’s roadways participating in the program are shorter on average in length than those in other parts of the city, the report found.

Transportation Alternatives

The number of listed Open Street compared to those found to be “active” with actual barricades in place.A key problem is that Open Streets rely largely on volunteers and community organizations to operate, charged with posting signage and setting up and breaking down barricades each day/ This “sets up a natural inequity between neighborhoods that are time-poor and those that are time-rich” the TA report notes. It points to GoFundMe pages set up by community groups to raise money for local Open Street expenses: A fundraiser for one along 5th Avenue in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park has raised just over $10,000, while another gathering funds for a different stretch of the roadway in wealthier Park Slope has garnered more than $30,000, surpassing the organizers’ goal.

Earlier this year, the mayor said the city would provide $4 million to go towards “community support” for Open Streets in this year’s budget, but it’s not clear if money has been allocated yet. The DOT did not immediately respond to a request for comment about the funding. The city’s Department of Small Business Services’ website is currently accepting funding applications from community organizations, which can apply for $50,000 grants to support Open Street events held between March 3 and the end of 2021; $100,000 grants are also available for city- or borough-wide organizations to support programing taking place before June 2022.

Transportation Alternatives is calling for the city to address these equity issues by making Open Streets “permanent, 24/7 car-free fixtures of the streetscape,” pointing to the positive impact they have for communities, including fewer injuries from traffic crashes on the streets taking part in the initiative. The group argues that the city should redesign participating roadways, installing “permanent and largely immovable” barricades that wouldn’t require volunteers to set up and take down.

The organization also recommends that the city allocate funding and other resources for Open Streets in the most undeserved neighborhoods—those that suffer disproportionately from high rates of traffic violence, asthma and air pollution, and which lack adequate park space. The city itself should take over primary operations for these streets, the report argues, rather than relying on community groups to do so (a bill passed by the City Council in April and set to take effect this month, will require the city to serve as the main steward for a minimum of 20 Open Streets in underserved areas).

The DOT called the survey “inaccurate,” saying there are currently 47 miles of Open Streets in operation (the TA report tallied 24 miles of Open Streets that its survey found to be “active,” meaning volunteers with the group observed barricades in place there during survey visits this summer. Mayor de Blasio has said his goal is 100 miles of Open Streets).

“We actively and frequently check on the status of our Open Streets, and we’re confident that a lot of these streets are, in fact, operational—despite what a canvasser might have seen on one isolated visit,” a spokesperson for the agency told City Limits in an email. “There are also Open Streets that were recently updated on our maps, which wouldn’t have been counted in TA’s report.”

Transportation Alternatives defended their findings.

“The de Blasio admin can have a list showing more miles of Open Streets, but with all of the failures of equitable implementation so far, what matters is what is active on the ground,” TA Spokesperson Cory Epstein told City Limits in an email. “We invite the admin to travel to all Open Streets locations and ensure they are properly functioning, meeting the needs of neighborhoods, and supporting New York City’s recovery.”

You can read the whole report here.