As the June primary election approaches, advocacy groups have raised concerns about voting access at Rikers Island and other facilities, saying New York should follow the lead of cities like Chicago, Los Angeles and D.C. in bringing in-person voting to jails.

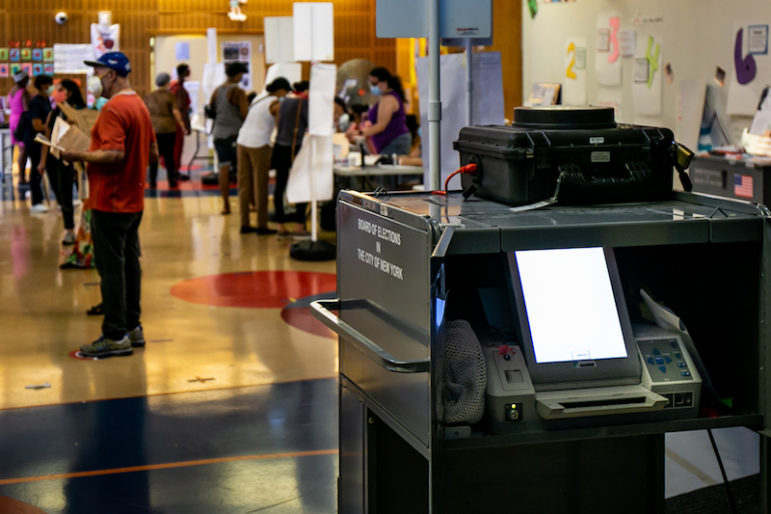

Adi Talwar

A ballot-marking device at P.S. 94 in the Bronx on Primary Day in 2020.This year, New Yorkers will get the chance to cast ballots in pivotal elections that will shape the city for years to come: choosing a new mayor, comptroller and City Council members.

But for the more than 5,000 people being held at Rikers Island and other city jail facilities at a given time, voting can be a bigger hurdle. New Yorkers behind bars are largely limited to voting by absentee ballot, and so must “rely entirely” on the city’s Department of Corrections’ staff for information, registration forms and to ensure absentee ballots get delivered, criminal justice advocates say. Dozens of advocacy groups penned a letter to city officials Thursday looking for information on how jails are handling voter access ahead of the June 22 primary; the last day to register to vote in that election is May 28.

“We recently learned from our incarcerated clients that DOC was not meeting its obligations to facilitate access to voting in NYC jails,” the letter reads. “The overwhelming majority of the clients we spoke with had not received voter registration information, they confirmed that there were no posters or signs with voter information, and that they had not received voter registration education.”

DOC officials, however, say outreach plans are underway: In the coming weeks, voter packets in both English and Spanish will be delivered to those in custody which will include information on voter eligibility, upcoming election deadlines, instructions for how to complete and submit needed forms as well as guidance on the new Ranked Choice Voting system. Those in jail will also be able to request materials in additional languages if needed and program staff will be able to answer questions and assist people in filling out forms, according to the agency, which says it hand-delivered 663 completed voter registration forms ahead of the last June 2020 primary.

“The Department has gone above and beyond to facilitate voter engagement in our facilities. From voter registration drives, to hand-delivering voter registration forms, we’re committed to keeping people connected to their civic rights and involved in the communities they will one day reenter,” DOC Deputy Commissioner of Public Information Peter Thorne said in a statement.

Advocates, however, say the city could be doing more. They are specifically calling for the DOC to establish early voting at each of its facilities so those in custody can cast their ballots in-person, following the lead of cities like Chicago, Los Angeles and Washington D.C., all of which have set up poll site in jails in recent years.

“Here, we’re really lagging behind,” in terms of voter access in jails, says Anthony Posada of The Legal Aid Society’s Community Justice Unit, which has been working with the DOC for the past several years to organize in-person voter registration drives, sending volunteers to Rikers Island to talk to eligible voters and encourage them to exercise their right to vote.

“It worked more efficiently when there were either stakeholders and volunteers coming in to do that civic engagement,” Posada says, saying the COVID-19 crisis has made it harder for his group and other advocates to monitor how the city’s outreach efforts are going behind bars. “The pandemic came and that sort of stopped everything. We weren’t able to continue going in, for obvious reasons.”

Legal Aid says it has still not gotten numbers from the DOC regarding voter access during the November 2020 election, including how many voter education presentations were conducted in city jails, how many people received absentee ballots and whether they were able to cast their votes.

“It also speaks to the fact that we need a city law that can really hold DOC accountable,” Posada added, to ensure outreach efforts taking place are more than just “a stack of papers in the corner at some location in Rikers Island were people won’t be able to see it.”

Advocates say proper outreach is essential to dispelling common myths and misinformation around incarcerated people’s voting rights, including the mistaken belief that experience with the criminal justice system precludes New Yorkers from casting a ballot. While state rules bar those currently serving time in prison from voting, and parolees with felony convictions need to request a pardon from the governor to have their voting rights restored, those on probation and with past misdemeanor convictions can still vote. The vast majority of people in city jails are awaiting trial and have not been convicted of a crime.

“While they’re there, these rights should be respected and given the dignity they deserve, especially in elections that have so much impact on their lives,” says Posada.

Early in-person voting in city jails would also solve a timing conundrum in the city’s election calendar: the last day to postmark an application for an absentee ballot for the June 22 primary is June 15, and the ballots themselves must be postmarked by primary day, meaning New Yorkers who enter DOC custody between those two dates won’t be able to vote unless they’d already mailed their ballot in beforehand.

Posada and other criminal justice advocates say civic engagement is an important aspect to successful re-entry, as voting can help incarcerated people feel more connected to their communities.

“When that’s not taking place, people are just made to feel that their voices don’t matter,” he added.