An estimated 5,000 restaurants across the city were predicted to shutter by February 2021 due to the pandemic. While there’s no officially tally, the loss of Latino-led businesses in New York was already a worrisome trend prior to the crisis.

Adi Talwar

El Cocotreo, a Latino-owned restaurant in Chelsea, went out of business in the first quarter of 2021 due to the economic pressures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.This article originally appeared in Spanish. Lea la versión en español aquí

The restaurant tables were left clean, no traces of food or dust, as if waiting for the next diners, who would no longer arrive. Mirian Mavarez wanted to leave them spotless, so she went over each one of them once more and wiped them again. It was her way of saying goodbye, of telling the tables and the place that they would be fine.

The fridge would remain there, clean and empty. The raw meats were given away to food delivery workers. Plates, silverware, and cooking utensils were donated to Housing Works and the remaining juices and food went to a foundation. Luis Quintero, meanwhile, was turning off the restaurant lights one by one.

When the place was in darkness, Mavarez went to the door. She turned to look one last time at the place where she had started working 17 years ago and expressed gratitude. “You know what, Cocotero?” Mavarez said, “Thank you very much. You don’t close, doors have been closed. You stay here, but I know I’ll see you somewhere else.”

Both went out. Quintero closed the doors. Mavarez held back tears, took down the Venezuelan flag hanging from the awning, then made a video giving the news to the restaurant’s followers on social media.

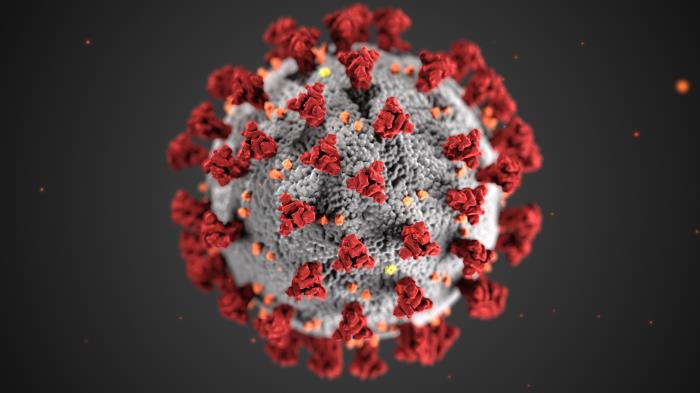

“Today it closes the doors, like many other businesses here in New York City,” says Mavarez, with the flag in hand in the Instagram video. A year into the pandemic, restaurants in New York City continue to close their doors and El Cocotero, one of the few Latino-owned and managed restaurants in Chelsea, is among them.

There is no official figure on how many restaurants have closed during the year-long pandemic. The NYC Department of Small Business Services does not keep a tally. The Manhattan Chamber of Commerce is also not keeping a count, although as noted by Jessica Walker, the chamber’s president and CEO, they intend to present a report on the impact of the pandemic by May, in which they could project an estimate of closures.

Estimates suggest a hefty toll. During the early months of the pandemic, between March and August 2020, some 1,200 restaurants were reported to have closed in New York, but by December that estimate had more than tripled to 4,500, and to 5,000 by February 2021. According to Opportunity Insights’ economy tracker, as of March 21, 2021, the leisure and hospitality industry in the city had shrunk 57.4 percent and the number of small businesses was down 40.1 percent compared to January 2020.

Harder to know is the number of shuttered restaurants that were run by Latino immigrants, such as Mavarez and Quintero, who left Venezuela more than 20 years ago. The loss of Latino-led businesses in New York was already a worrisome trend prior to the pandemic: Between 2012 and 2017, there was an 8.7 percent reduction in the number of Latino-owned businesses in the city.

El Cocotero was a long-established restaurant visited by Venezuelan beauty queens, celebrities such as Antonio Banderas, and Venezuelan politicians such as Henrique Capriles. At its peak, it had an annual turnover of more than $1.5 million.

The last time El Cocotero had been able to pay full rent was in February 2020, when the restaurant closed for two weeks to renovate the roof and reopened only to close again days later because of the pandemic. They reopened again at the end of April.

In the following months, they paid a portion of the rent from monthly sales. According to survey data by the NYC Hospitality Alliance, 92 percent of restaurants and bars couldn’t afford to pay December rent, a trend that has been increasing since June (80 percent), July (83 percent), August (87 percent), and October (88 percent).

“I worked the most in those last few months,” Quintero says by phone. “I’ve never worked so hard in my life.” Four people were in charge of doing all the work that used to be done by eight in two shifts.

Since reopening in April, El Cocotero’s take-out sales and deliveries accounted for less than one-third of the sales needed to operate, matching the trend described in the most recent New York State Restaurant Association survey.

“We were fighting a very strong enemy: cash flow,” Quintero says. During the pandemic, the restaurant was grossing about $16,000 per month, down from about $60,000 monthly pre-pandemic. Since opening its doors on April 8, 2004, El Cocotero’s sales had never been that low.

They received a letter from the landlord demanding payment of more than $60,000 in rent. Back in January, they still thought they could hold out a little longer. Their hope hung on the second round of federal employee payroll assistance for which they had applied in December, and that would allow them to extend operations for a little over a month, about as long as the first PPP loan lasted. But that additional assistance never came, and there was no aid from the city or state.

Adi Talwar

The size of the debt became unbearable. On Valentine’s Day, while many people were reserving a seat to celebrate and restaurants were once again being allowed to host indoor dining, Quintero called Mavarez. That evening they made the decision to close.

Mavarez and Quintero say they realized during the pandemic that their customers had been local workers and tourists visiting New York. So they tried to attract new customers from the area by selling hamburgers, fries, waffles, and a whole new menu that is not typical Venezuelan food. It didn’t work. They also lowered production costs as much as possible and bought just enough food to avoid waste. That didn’t work either.

“Manhattan is not full of Venezuelans,” says Mavarez, as she explains that all areas have not been affected equally. “I have friends who have done well.”

In areas with a strong Latino presence such as Jackson Heights in Queens, and specifically in the area served by the 82nd Street Partnership, “We lost only one restaurant and actually had three open—they were all on track to opening pre-pandemic,” says Leslie Ramos, executive director of the Partnership.

“To be honest, the one we lost would probably have closed anyways. The owners took over an already failing business in a high turnover location,” she says.

For Walker, two things have helped Manhattan restaurants stay on their feet: “Having a strong online presence” and secondly, “making the pivot quickly to have a temporary license to provide alcohol and beverages, bringing in more revenue.”

But in El Cocotero’s case, this was not enough: more than 5,660 followers on Instagram, more than 7,600 check-ins on Facebook, and a license to sell wine and beer.

“Before I made the decision, I would arrive early and go out and look around. I saw many places that were closed,” says Mavarez. “The restaurant on the corner, it’s an upscale one and its diners have maintained.”

The survey published last November from the New York State Restaurant Association and the National Restaurant Association predicted that 54 percent of eateries would probably not survive the next six months without federal aid, and so it was for El Cocotero.

Now, two weeks after closing the restaurant, every time Mavarez passes by a closed store, she thinks of and wishes the best for the people behind the business. “I run the movie of what happened to us in my mind and put myself in their shoes. Then I think: I hope they’re okay, because it hurts.”

3 thoughts on “One More Casualty of COVID-19: The Death of El Cocotero”

We are from the Central Valley of California and hadn’t had any exposure to Venezuelan food or culture. El Cocotero introduced my daughter to arepas. She became an aficionado after her first bite and she continued to eat here and bring her friends during school (NYU) and after she graduated.

When we would come to visit, this was her go-to place to eat in NYC.

My daughter has so many great memories of fun times at the restaurant and of your great food, especially the arepas. She is so sad to see you close.

Very sad, we too, tried our first Venezuelan meal there last New Year while visiting our son in college.

My twin daughters are headed to school in NY in the fall. They just went by to eat at El Cocotero, and were saddened by it not being open.

Luis was very kind and friendly. We enjoyed our time there and would have certainly been back.

We are heartbroken by this. Luis,Mavarez and that place was like family – we had so many birthdays, holiday parties and just great meals there- the Tequenos and Guadapinta will never be replicated. We miss you. besos….