As City Limits celebrates its 45th anniversary, a look back at stories published each year of our four-and-half decades covering New York.

The first issue of City Limits, published in February of 1976, was not a flashy production. Launched in the midst of New York City’s fiscal crisis, the inaugural issue — created to foster “more communication within and among people and organizations in the movement to save and improve housing,” according to a note from the editors at the time — included a short profile of a nonprofit housing developer in Brooklyn, a recap of a City Planning Commission hearing and a hand-drawn ad for a housing organizers’ workshop being planned for Valentine’s Day.

It’s been 45 years since that first issue was published, and while much has changed, New York City in 2021 is facing many of the same challenges it did in 1976 — an affordable housing shortage and a looming fiscal crisis among them.

City Limits’ coverage and reach has expanded since its founding days, but our mission remains the same as those earlier years: To inform and empower New York City residents to create a more just city. To mark this month’s anniversary milestone, we’re looking back at some of the stories we’ve published during the last four-and-a-half decades covering New York.

1976

Community Development: Lawsuit Planned

The second-ever issue of City Limits included a report on concerns over how the city’s Housing Development Agency (HDA) was spending federal funding that was supposed to be set aside for “the housing and related community development needs of the poor and near-poor residents” of the city. The money was instead “being allocated for private business development, sewers in Queens and Staten Island, seaside boardwalk rehabilitation and other purposes that sound and smell more like political pork-barrel pay- offs than projects to help the needy in a city on the brink of disaster.”

Many community groups feel that what the city is doing with these funds is not only immoral and outrageous, but also probably illegal.

-March 1978

As Ruth Garcia of Adopt-A-Building said to the Board of Estimate on February 10th, (and later reported in the Daily News, February 11th): “When you apply to the federal government, you use the South Bronx, Brownsville, the Lower East Side to show how many poor people the city has, but when you get the money, you use it for Queens sewers and Fordham Plaza shopping centers instead of for the areas that helped get you the funds. That’s called a rip-off.”

1977

Doing the ‘Do-able’ In Sunset Park

Sunset Park in Brooklyn is on the threshold of its second major attempt in five years to rehabilitate its stock of old frame houses and reverse the abandonment that dots some blocks and virtually blots out others.

In its first try, the neighborhood saved 15 buildings and set a precedent for rehabilitation of one and two-family abandoned homes. Unhappily, the cost was so high, due in large part to financial hardships wrought by the government, that the project drew to a close on a somber note of disappointment.

-December 1977

“I would guess it was the broken promises kind of thing,” said John Gallagher, an architect and last surviving staff member of the Sunset Park Redevelopment Committee. Once again, the success of the effort to turn this struggling neighborhood around depends in a large way on government. And while there are already some indications that it is hatching new obstacles, Gallagher remains optimistic.” Essentially, our second chance hasn’t started yet. But things haven’t looked this good in quite a while.”

1978

7-A Law Gives Tenants a Way to Seize a Building—Legally

The saga of a group of elderly tenants who seized control of their apartment building from the landlord began two years ago under familiar circumstances for Harlem. The tenants had no heat or hot water. Their home at 92 st. Nicholas Ave. was in dangerous disrepair. The landlord had threatened to abandon. In September, 1976, Leopold Altman, agent for the Gerjo Realty Co., owed $65,000 in back taxes on the building. The tenants owed him, he said, $13,600 in back and current rents.

At first, tenant Laura Batey worried about what would happen if the landlord walked away. “What worried me most was what would happen to all the good, paying tenants-most of us senior citizens on Social Security,” she said. “We didn’t want to have to go out in the cold and find new places to live.”

Another tenant, Enid Gobem, said she was angry “that those who were paying had to suffer because of those who weren’t.

-Margaret Gillerman, September 1978

“But I can understand why they didn’t pay,” she said. “That Altman, he wouldn’t do nothing for us. He wouldn’t paint. He wouldn’t plaster up holes in the ceilings or walls or fix floors or bad plumbing. He wouldn’t put glass in the front door. All he wanted was that rent.”

1979

Welfare Tenants Face Forced Rent Payments

Each month, some middle and upper income tenants withhold rent to pay for repairs or services that landlords have failed to provide. Newspaper and television editorials do not attack them for destroying the city. Politicians do not petition the federal government to step in and make it impossible for them to do so. Mayor Koch does not accuse them of theft.

Yet over the past year there has been a concerted campaign involving landlords, the mayor and some Bronx politicians on behalf of a policy, and a particular project implementing this policy, to deprive many poor tenants of the ability to withhold rent and to use it for needed repairs and services.

-Timothy J. Casey, February 1979

1980

Counting New York’s Invisible People

In 1980, City Limits’ Editor Tom Robbins reported on the stories of Census takers and the challenges they faced in getting an accurate count of the city’ population, particular in communities hardest hit by the housing crisis at the time:

Apparently no one has been satisfied with the procedure for distributing Spanish-language forms. In order to get a form in Spanish, a resident had to check off a box on the form received and then mail it back, then await another form in the mail. “You had to be determined if you wanted to get counted,” said Nazario.

These were not the only factors working against a true count of the city’s Hispanic population. The highest concentration of Puerto Ricans and Latin Americans are in neighborhoods such as the South Bronx, East Harlem and the Lower East Side, all areas which have borne the brunt of housing abandonment.

-Tom Robbins, October 1980

…

Buildings which are partially vacant, but where families may still be living, are supposed to be entered and counted. But for census takers working alone, as most were, the buildings’ darkened hallways and stairs proved to be strongly inhibiting factors. Steve Glusman recounts how on one Harlem street with many decaying buildings, he was forewarned by neighbors not to enter certain tenements.

1981

Breakdown on the Transit Tax Express

As New York City’s transit creaks toward what many riders view as almost certain disaster, a real estate tax measure designed to infuse the system with much-needed operating dollars may soon be derailed.

The measure, a special tax on the transfer of large, “income-producing” properties concentrated in Manhattan, was opposed during the State Legislature’s fall session by the city’s real estate industry and Mayor Edward Koch, who unsuccessfully sought to replace it with increases in two existing real estate taxes. That proposal, in turn, was attacked by public interest and riders’ groups as a meager substitute, and it failed in a mid- November State Senate vote. But when legislators return to Albany for a special session starting December 16, so will the lobbyists from both sides of the transit tax track.

-December 1981

1982

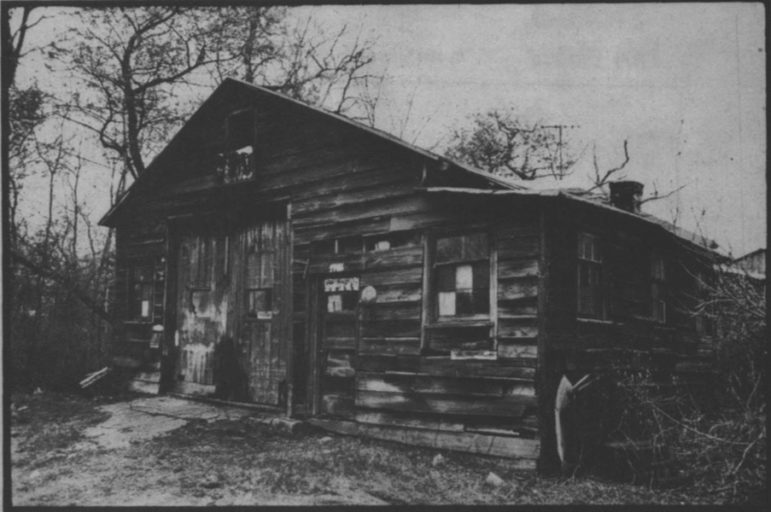

Staten Island’s Sandy Ground Holds On To History

There’s a blacksmith shop up the way from the Pedro’s house on Frederick Road. Its wood is dark and worn from the weather, use and years. The building leans and the roof of the shop is sunken. High grass surrounds the shop and a horse stable neighbors it. The road before the building is paved, but little traffic passes it.

-Yvette Moore, June/July 1982

Despite the bucolic scene, this is New York City. It is a community in Staten Island called Sandy Ground. Sandy Ground is the oldest surviving community in New York State founded by free Blacks. The original settlers in the small antbellum village, located on the southwestern tip of Staten Island, were oystermen by trade.

…

For the last four years, descendants of those settlers have been working to preserve their culture and the physical state of their community, which is threatened by encroaching development in the area. That development, in the form of garden apartment-style row houses, has intensified since the recent opening of the West Shore Expressway, a route that makes other parts of Staten Island and New York City more accessible for area residents.

1983

Prisons: The State’s New Housing Plan

Under the Urban Development Corporation Prison Construction Act of 1983, the agency has been given legislative approval to sell $380 million in bonds to finance the construction of new prisons around the state. Currently, one of the prisons is slated for the South Bronx.

…

-Tom Robbins, October 1983

In addition to the $380 million for the UDC’s prison construction program, the legislature voted $320 million in capital budget funding for the Department of Corrections, said Robert Gangi, who coordinated a statewide effort to defeat the 1981 bond initiative.

“Prisons are obviously a form of housing for the poor,” said Gangi. “It’s a dramatic example of the shift in social and governmental priorities. In the 1960s there was a recognition of the need for help for the plight of poor people.”

1984

Can Artists Stay as Lofts Go Legal?

There’s no cure for an ailing neighborhood like a good sprinkling of loft-dwelling artists. At least that’s what City Hall has insisted over the past two years as it has pushed its artist housing projects in city-owned, tax-foreclosed buildings.

But while those proposals to create needed artist housing get strong administration backing, the largest body of the city’s working artists are clinging perilously to their still quasi-legal living and working loft spaces. And although some progress has been made, loft tenants fear that the mayorally-appointed board tapped to carry out legalization may ultimately lose more artists’ living spaces than it protects.

-Lisa Wilde, November 1984

1985

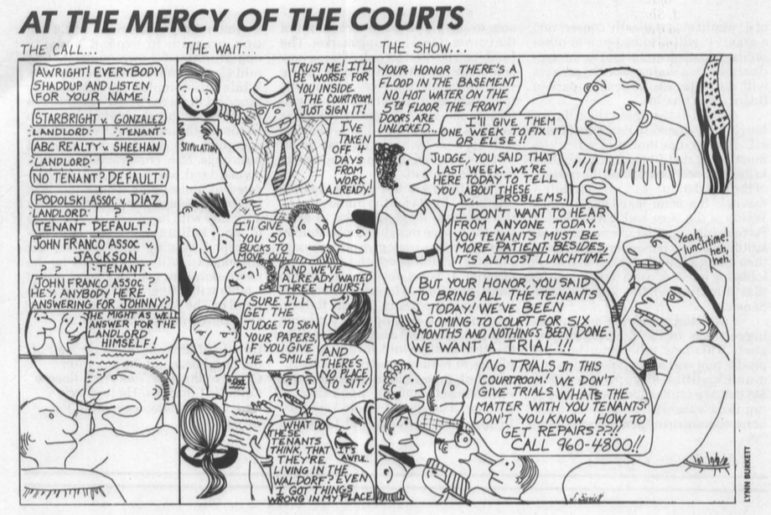

At the Mercy of the Courts

City Limits/Lynn Burket

An illustration of the struggles tenants faced in NYC housing courts, published in the June/July 1985 issue of City Limits, by artist Lynn Burkett.

1986

The Company of Women

Women-only housing is on the decline in New York City. Only 13 such residences still exist. All but three are run by religious or ethnic societies- the same groups to run the first homes prior to, and since, the turn of the century. Such housing was originally created for two reasons: the perceived need to protect, innocent, young women from male sexuality and employers desire to keep a constant, watchful eye on their work- force.

But if times have changed and with them the morality of women in ‘sin city,’ the demand for women’s residences is alive and well. The problem is that while demand is still strong and need even stronger, women’s residences are falling prey to housing market forces. Luxury conversions to private ownership or to co-ed habitation have whittled away at housing for women that began a century ago.

-Eleanor J. Bader, March 1986

1987

The Taking of Hunters Point

When Arthur Nathanson first heard of the plan to build a 42-story tower in Hunters Point, Queens he says it made him think of the film “2001: A Space Odyssey.” He recalled the opening scene where a huge monolith comes hurtling down on the savages below. The green glass tower Citicorp plans to erect in the midst of this community of two-and three-story homes and manufacturing plants gives Nathanson a similar sense of omnipotent forces unleashed.

-Doug Turetsky, January 1987

1988

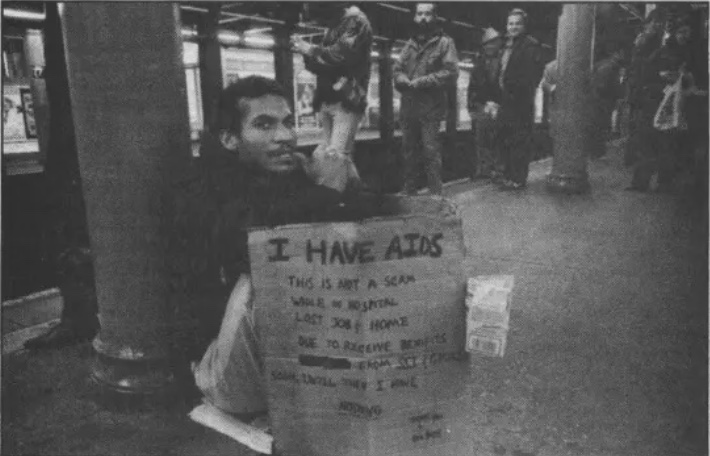

Double Jeopardy: Facing AIDS and Homelessness

Two of the city’s most critical social problems intersect when people with AIDS face homelessness, yet advocates charge city officials with fiddling while the flames of AIDS sweep across the metropolitan area.

-Beverly Cheuvront, February 1988

In a far-too-common example, one man hospitalized with AIDS was slapped with an eviction. Since hospitals are not allowed to discharge AIDS patients who have no home, the tenant faced a quandry: Too ill to fight his landlord in court, yet well enough to leave the hospital, he was forced to remain – at an average cost of $600 daily – until he could enter one of the scarce residential programs available to people with AIDS.

1989

Power and Profits? Community Health Centers Get a Check-Up

Created during the heady days of the 1960s, neighborhood health centers promised to revolutionize health care for the poor. For as little as $2 per visit, these clinics were created to provide preventative medicine, nutrition advice, dental service and family planning as well as personal service from committed physicians. Control was placed in the hands of the community.

-Lisa Glazer, March 1989

…

While many of the nation’s 600 community health centers still strive to fulfill this ambitious mandate from the War on Poverty era, almost one- third of New York City’s 13 federally-funded community health centers have drifted from their early ideals. Instead of providing first class health services for uninsured New Yorkers, these clinics have become local power bases-centers where neighborhood leaders build political influence, engage in real estate management or, in some cases, pursue personal profit.

1990

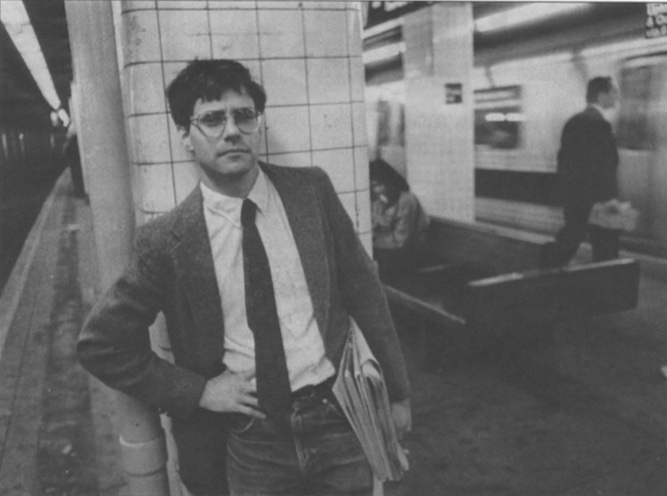

Is New York’s Transit Off Track?

City Limits/Andrew Lichtenstein

Joe Rappaport, of the Straphangers’ Campaign, pictured in 1990.On a typical Thursday night, it’s standing-room- only on the gleaming new silver cars of the #2 train coming into Manhattan from the Bronx. Air-conditioned and grafitti-free, it comes to a smooth stop–and sits there, right in the middle of the dark tube between stations. As the unexplained delay lengthens from five minutes to 15 minutes, a young man growls a sentiment that starts a dozen heads nodding grimly: “If I see one of those, we’re-coming- back-so-you-come-back signs, I’m going to tear it down and rip it apart.”

-Margaret Mittelbach, December 1990

If subway officials thought they could endear themselves to riders with their current $2.1 million advertising campaign, “The Subway. We’re Coming Back. So You Come Back,” they should have thought again.

1991

The Housing Authority: Separate and Unequal?

The culmination of a five-year research effort, the Legal Aid lawsuit claims that for years the housing authority has used separate and unequal methods of tenant selection – one for whites, another for African-Americans and Latinos. According to the lawsuit, these methods steered white applicants to predominantly white projects, while these same projects were often off-limits to blacks and Latinos.

-Lisa Glazer, April 1991

…

Violet B. Hamilton, the head of the housing authority’s Tenant Advisory Council, doesn’t waste time with analysis. “I don’t bite my tongue-the housing authority is a racist and discriminatory organization,” she says. “There are some developments where you just can’t be white enough to get in.”

1992

Open Questions, Open Space: Debating the Future of Floyd Bennett Airfield

While sections of the old airfield are pleasant and natural, the park seems uninviting at first glance and is not widely known by the New York populace. Old hangars and the control tower look forlornly over grass-infested tarmac. Driving down the old runways and access roads, visitors pass dilapidated air support buildings, a coast guard station, and an Armed Forces Reserve Center. To the east, planes rise and descend at Kennedy airport, while to the north rises the Manhattan skyline. This is not the average park site.

-Michael O’D. Moore, March 1992

The future of this section of Gateway National Recreation Area has been the topic of heated discussion recently as the National Park Service considers proposals that would use private developers to renovate derelict old hangars in the park.

1993

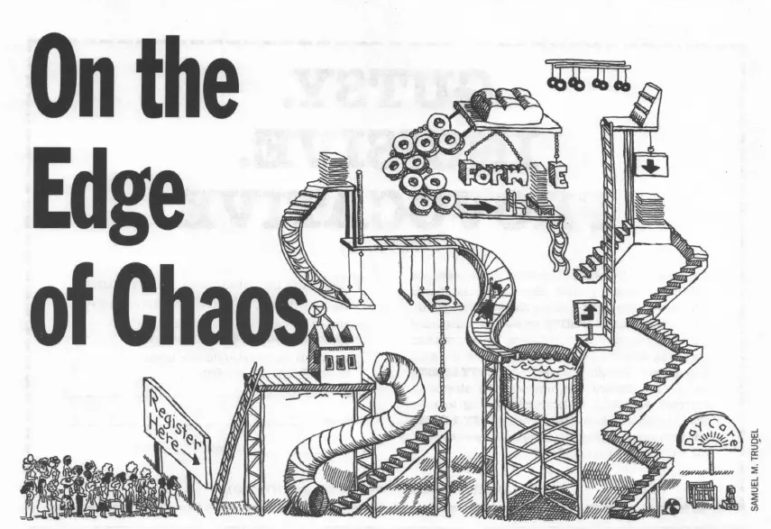

The Trouble With Day Care

One year after the city adopted state-mandated changes in the system for regulating family day care, most of the intended goals remain elusive and the changes have undermined government-funded daycare programs run by neighborhood organizations for children of low-income families.

-Andrew White and Steven Wishnia, June/July 1993

1994

History Repeats: Did MetroTech Create Jobs for Fort Greene’s Unemployed?

Today, MetroTech is bustling with some 10,000 office workers. But most if not all of those employees came east when companines like Chase Manhattan Bank and Bear, Sternes and Company relocated their headquarters from Manhattan.

-Laura Washington, December 1994

Meanwhile, the residents of Fort Greene–the neighborhood literally across the street from MetroTech, home to 4,900 residents of three public housing projects and the most impoverished area bordering downtown Brooklyn–say they are still waiting to experience the economic benefit of the new, $1 billion complex. Asked if the MetroTech arrival has benefited the community they live in, the prevailing answer here is a resounding, “No.”

1995

Recycling Retrograde: New York Abandons a Multi-Million Dollar Industry

Even the one aspect of recycling the city was making some progress in–curbside collection–has slipped backwards. By law, the city is supposed to be diverting at least 20 percent of its waste stream into recycling by this June. In fact, according to the Sanitation Department, the diversion rate dropped last year from 14.5 percent to 13 percent, despite the fact that 1994 was the first year curbside recycling was in place citywide.

-Jame Bradley, June/July 1995

1996

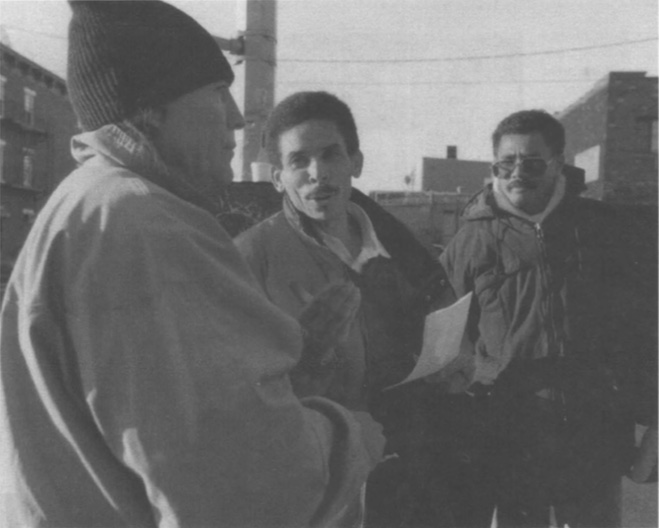

Street Corner Labor

City Limits Archives

Organizers meet with with day laborers in Queens.One key staff member is a broad-shouldered, 38-year-old Peruvian named Cesar Monzon. His story is much like those of the other day laborers. Monzon came to the United States hoping to find work that would support his family. Struggling with the language barrier, he worked 12-hour days, seven days a week at a fish processing plant in Brooklyn. Every week he sent home a little money. But after a month of being paid below the minimum wage with no overtime and no benefits, he quit and began looking for work at the esquinas.

–Julian Camilo Pozzi, January 1996

Monday through Sunday, he waits from 4:30 a.m. into the late afternoon for jobs. “I wake up every morning and I go [to the esquinas] knowing I have to work. I am fighting to bring my family here. I ask God that he help me, that he won’t abandon me.”

1997

NYPD’s Cop Out: Why We’re Losing the Battle Against Police Brutality

Reconciling the demands of the job with the needs of the community is the task the NYPD should be undertaking, especially in the wake of the alleged brutalization and sodomy of Abner Louima in Brooklyn’s 70th Precinct. But apart from the deeply flawed $15 million “Courtesy, Professionalism and Respect” campaign, the department has done little to attack the problem.

While the country’s most lauded department has become a national model for innovative approaches to attacking street crime, it has failed to adopt important innovations other cities are using to eradicate the problem of in-house violence.

Cops and cop critics recognize that real change will have to focus on prediction and prevention, including a more intense effort to screen out unfit cadets and a much more serious police- training regimen.

-Chris Mitchell, December 1997

1998

Seven and a Half Days

Woodhull Hospital serves two of Brooklyn’s poorest communities, Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant, where nearly half the residents have incomes below the federal poverty level. Woodhull is one of the city’s 11 public hospitals, operated by the Health and Hospitals Corporation, an agency that is increasingly responsible for treating the city’s uninsured poor. In 1996, HHC treated 46 percent of all psychiatric inpatients in the city.

I wasn’t suicidal when I entered Woodhull ‘s emergency room. I went in as a reporter. The purpose of going undercover was to evaluate New York City’s system for providing crisis-level mental health services to low-income people.

-Kevin Heldman, June/July 1998

1999

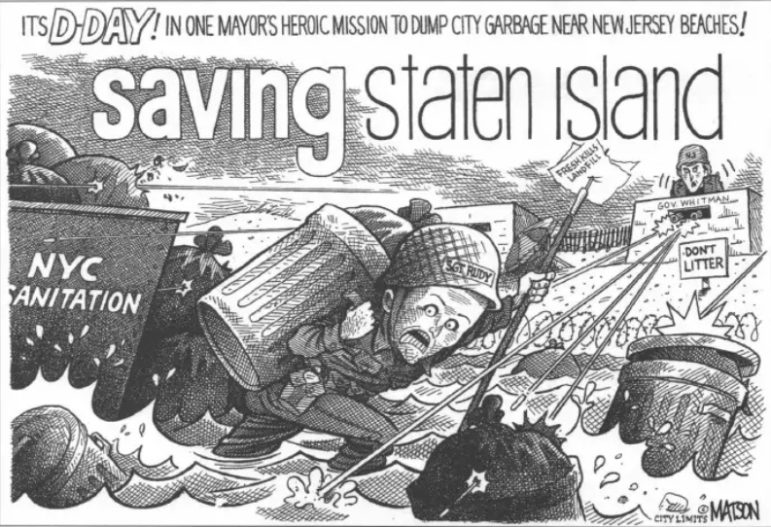

City Limits/R.J. Matson

An editorial cartoon featured in the February 1999 issue of City Limits, depicting then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s proposal to send the city’s garbage to New Jersey instead of the Fresh Kills Landfill on Staten Island.

2000

Remaking the Rent

It’s a good thing Tony Bennett didn’t leave his heart in New York. He would have gotten palpitations in December, when a group of tenant advocates, armed with a karaoke machine, serenaded the Sheraton New York Hotel with their own lyrics to Bennett’s songs while the crooner himself performed inside at a birthday party. “I left my heart/In the landlords’ pocket/Flush with their cash/l’ll run for Mayor,” they sang to the 65-year-old guest of honor: Bennett’s boyhood friend from Astoria, City Council speaker Peter Vallone.

-Jarrett Murphy, February 2000

The picket, staged by New York State Tenants & Neighbors Coalition and the Metropolitan Council on Housing, was a sign of just how anxious advocates are as the city’s rent regulations head toward expiration this April 1. Rent control and stabilization operate under state laws, but the legislation requires the City Council to certify every three years that New York City still needs the regulations. If April Fools Day comes without such a vote from the council, the rent regulations- which limit yearly rent increases on roughly one million regulated apartments and protect tenants from harassment- will disappear.

2001

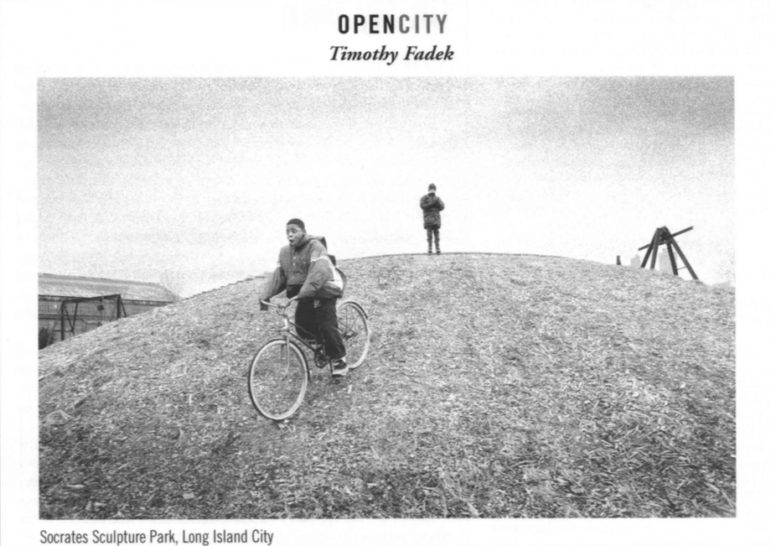

A photo by Timothy Fadek of Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens, featured in the December 2001 issue.

2002

The Courage of His Conviction

With the West Indian Day Parade just hours away, steel pan drummers filled Labor Day morning with pulsating rhythms. As floats carried revelers along F1atbush Avenue for the pre- dawn Caribbean celebration of J’ouvert, a special homecoming took place.

Waving the flag of his native Trinidad, 39-year-old Colin Warner rode on a float of his own, family and friends by his side. Band members swayed to the music, wearing T- shirts that declared “VICTORY FOR OUR HERO COLIN WARNER.”

Warner, an electrician’s apprentice who lives in East Flatbush, has lived through the impossible, twice over. He went to jail for 21 years for a murder he did not commit, and successfully mounted his own case-with the help of a devoted childhood friend, Carl King-to convince a judge to set him free.

-Curtis Harris, January 2002

2003

Beyond the Bowery

So much about the Bowery has changed, including its physical scale, that it’s easy to miss the Andrews Hotel, tucked between a brand- new luxury high rise and the bright display windows o f a neighboring purveyor o f lighting fixtures. A narrow six-story building of sooty brick, criss-crossed by an iron fire escape, the Andrews is a typical example of what has defined this neighborhood for almost a century: the flophouse.

What it has offered its residents is basic in the extreme: a narrow bed in a plywood cubicle, cheap rent (often paid weekly), and, above all, anonymity. As one resident puts it, the unwritten rule at the Andrews has always been, “Don’t bother anybody and they won’t bother you.”

Only 15 years ago, 3,600 men still lived in “cubicle” hotels on the Bowery. Now less than a thousand and perhaps as few as 500 remain, scattered among eight enduring lodging houses. One by one, hotels that served the needs of generations of Bowery men are being transformed.

-Bob Roberts, July/August 2003

2004

The Children’s Hour

The organizations that have housed children for all these years are suddenly finding themselves all built up with nowhere to go. They’ve acquired extensive infrastructure, accumulating office leases and verdant campuses. These organizations are paid for this work under contract with the city-paid per child. Fewer children spell less money.

Under the Bloomberg administration, the Administration for Children’s Services suffered some of the biggest declines of any New York City government agency. Foster care spending alone declined by $82 million during the first two years of the Bloomberg administration, down from $750 million.

“The trend is for agencies to go out of business,” says Edith Holzer, the spokesperson for the Council of Family and Child Caring Agencies, a trade association of foster care providers.

Xiaoqing Rong, December 2004

2005

Stocking the Market

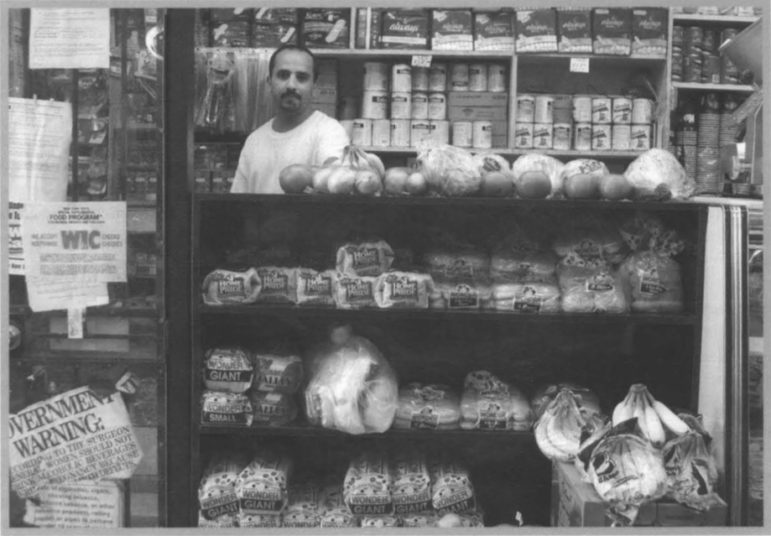

City Limits/Amy Bolge

“I eat good at home. I don’t buy a lot of frozen food, and I eat a lot of rice and beans,” he says. Yet fruits and vegetables tend to fall low on his list, he says, because decent ones are hard to come by. “Quite a few bodegas don’t keep their food fresh,” he says, leaning against a store window plastered with ads. “This is a grimy neighborhood. We could use some nice, fresh produce over here.”

The city’s health department is beginning to agree. Obesity rates in the city’s poor neighborhoods are staggering, and coincide with high incidence of diabetes, heart disease and cancer. Looking for ways to counter those stats, the department of health is considering a radical solution: Transform bodegas-purveyors of the high calorie, low nutrition foods that have been faulted for fueling the obesity epidemic-into sources of healthier foods like whole grain breads, low-fat milk, and fresh produce.

-Tracie McMillan, September/October 2005

2006

Saying Goodbye to Last Chance High

The green chalkboard still held the smeared shadow of a global studies lesson: “Aim: What are the countries and cities in North America?” But all the desks were empty. Textbooks and art supplies were packed up in cardboard boxes, and the school’s final student—ever—had just gone home. “It’s weird,” said teacher Rachel Matthews. “Nostalgic, sad. I guess we’ve come full circle.”

The Manhattan school, housed in a municipal building at the corner of Broadway and Leonard Street, is part of the city’s Alternative to Detention Program (ATD), created in 1971 to serve children ages 7-16 facing charges in Family Court. The program’s three sites are now officially set to close by early March, marking the end of a controversial experiment in juvenile justice—and prompting an outcry from advocates.

-Cassi Feldman, February 2006

2007

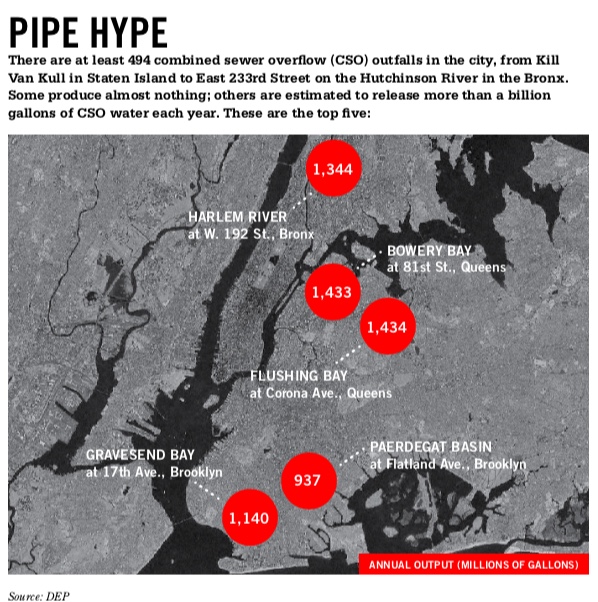

Water Pressure: Facing the Challenge of NY’s Endless Sewage Spill

But then you slip under Tremont Avenue, start to drift toward the Cross Bronx Expressway and peer into the shadows of the yawning concrete pipe embedded in the left bank. If it’s hot enough, you might smell the big hole before and after you see it, and that would tip you off to what that pipe does on rainy days: spew a mixture of stormwater and raw sewage into the Bronx River.

..The reason it happens is well known: The city’s sewage infrastructure, which combines the water running down street-level storm drains with what we flush down the toilet and spill down the sink, does not have the capacity to hold the additional volume of water when it rains intensely. As little as one-tenth of an inch of rain can cause an overflow. Put simply, rain gives New York City diarrhea—and it has for decades.

-Anna Lenzer and Jarrett Murphy, September 2007

2008

Who Counts and Who’s Counting? NYC’s Struggle to Graduate

Anthony’s got a problem. A baby-faced boy in a white hoodie with a pencil-thin jawline trace of a beard, he’s hunkered down on an upholstered bench, poised halfway between tears and a tough-guy mask. Anthony’s not yet 18 and a new father, with a son, Anthony, Jr., only two weeks old. His baby’s mother, who is 24, is pressing him to leave school to help support her and the baby. He’s got to choose, he feels, between being a man and finishing school.

-Helen Zelon, Winter 2008

…

Anthony is far from alone: Tens of thousands of young New Yorkers struggle to finish high school. Many simply don’t. The class of 2006 included 10,023 dropouts—one for every four graduates.

2009

The Chamber: A Week in the NYC Council

Councilman Jimmy Vacca’s aides have a rule for the hour-long ride from his district office in the East Bronx to City Hall: Don’t let the councilman drive. Vacca’s driving style is, well, cautious. The trip would take forever if he took the wheel, the aides say. Besides, Vacca’s got too much to do during the ride. No sooner has the car pulled out into traffic at about 9:20 on Thursday morning than Vacca’s on the phone to the district office he just left, telling another aide to call a local Sanitation Department official. “The street sweeper could not have come down here,” Vacca says, after spying leaves and trash along the curb. “Call him up and ask him what’s going on on Tremont Avenue.”

-Jarrett Murphy with Sarah Crean, Michelle Han, Curtis Stephen, Chloe Tribich and Helen Zelon, Spring 2009

2010

Hope or Hype in Harlem?

Students in the Harlem Children’s Zone achieve the results they do, Canada says, because they invest more: They invest more actual time in the classroom, with a far longer school day and a school year that begins in September and ends in early August. All Promise Academy students are in school about 60 percent longer than average public school students. Struggling students can spend twice as many hours in school as the average kid—in class and in tutoring or in small-group before- and after-school instruction. HCZ’s corporate and school leaders say they hold each child to high standards and expect teachers to do “whatever it takes” to achieve success. And the charters invest more money per child per year—nearly $19,000 in 2008—than the $14,525 the city spends on children who attend general-education programs in traditional open-enrollment public schools.

-Helon Zelon, March 2010

2011

Work In Progress: Residents Get More NYCHA Jobs

Jerome Mosley, a resident of the Thomas Jefferson Houses in Harlem, was unemployed and wanted to get work in construction—which would offer much better pay than the retail management job he had lost a year earlier. Despite filling out dozens of employment applications, he was reaching dead ends. Then in May he enrolled in the Bloomberg administration’s Jobs Plus program, where he heard about a New York City Housing Authority training program open to public housing residents like him. After taking a test and an interview, Mosley was chosen for NYCHA’s selective job training program.

…

–Diana Scholl, January 2011

“I’m ecstatic,” Mosley says. “Not only am I working, but I’m learning.”

2012

Traffic, Pollution, Accidents: Are Trucks to Blame?

New York is hardly a smoothly functioning city from any angle, but seen from the elevated cockpit of a delivery truck, with views that reach for blocks in all directions, down through fellow drivers’ windshields and across sidewalks full of unpredictable pedestrians, it is at its most chaotic. Obstacles emerge and recede; paths close down and open again. Human behavior – the decision to step or not step into traffic, to press the gas pedal or the brake – is jarringly erratic.

And as planners search for ways to untangle a knot of urban transportation problems, trucks emerge at every turn, an irreducible reality. A 2010 study by professors at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute counted more than 5 million of them within 100 miles of the city, making almost 257,000 deliveries every day in the five boroughs, with more than 40 percent of those stops in Manhattan alone.

-Jake Mooney, April 2012

2013

Push to Diversify City Contracting Falls Short of Goals

The story of the city’s minority- and women-owned business enterprises program—which aimed to substantially increase the share of city contracts going to those firms—is a story that does not mesh with the usual tale told about Bloomberg’s New York, of a city run efficiently, like a profitable business, using the latest technology and operated by a leader who sets goals and achieves them. New York City’s M/WBE program displays little accountability, incomplete or misleading data and continued failure to meet its goals.

A review of contract data, city documents and transcripts, as well as dozens of interviews with interested parties, suggests the program—admittedly a tiny piece of the city that Bloomberg will hand over to a new administration in January—was never a priority for the administration. Minority- and woman-led firms faced obstacles in qualifying for the work. And the law that created the program in 2005, as well as an amended version passed early this year, are full of contradictions and questionable numbers.

-Adam Wisnieski, December 2013

2014

City’s Fire Investigation Bureau Stretched Thin

“Theoretically you should go to every fire,” says a fire investigator who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak on the matter. “But where are you going to get the manpower?”

-Briana Duggan, May 2014

Since 2002, the city has cut the number of fire marshals by about half, yet the bureau of fire investigation, the division of the fire department charged with determining the cause of fires, has seen a 17 percent increase in investigations sent to its desks.

2015

As Housing Court Strains, Debate in Bronx Over How to Ease Crisis

Adi Talwar

The Bronx contains five of the 10 communities citywide that experience the highest incidences of family homelessness — University Heights, Morris Heights, Soundview, South Bronx, and Tremont. In total, 35 percent of all families eligible for shelter services come from the Bronx.

-Kate Pastor, February 2015

We as a court can control what we have here within our walls,” said Judge Jaya Madhavan, Bronx housing court’s supervising judge. “We can’t control the economy; we can’t control the things that cause people to not be able to afford their apartments anymore.”

2016

New York’s Security-Guard Training Requirements Routinely Flouted

In 1992, New York became a nationwide leader in efforts to clean up and professionalize the private security industry when Gov. Mario Cuomo signed the Security Guard Act. For the first time, beginning a couple of years later in 1994, security guards employed in New York were required to register with the state and go through mandatory yearly training.

But more than two decades later, as their resources dwindle, the state agencies in charge of overseeing the private security industry struggle to make sure companies and the guards they employ are following the rules. A City Limits investigation reveals a messy training school system in New York, full of discrepancies and misinformation, where it’s even possible to “buy” a certificate without going through any of the mandatory training.

-Adam Wisnieski and Jonathan Gomez, May 2016

2017

What Drives NYC’s Health Disparities?

Adi Talwar

We Run Brownsville, a women’s running club, offers fitness to runners.Though only about nine miles apart, Brownsville and Battery Park have over 10 years between them in the average life expectancy of their residents. In Brownsville—a neighborhood consistently ranked among the poorest and most dangerous in the city — life expectancy, at 74.4 years, was at a citywide low in the most recent Summary of Vital Statistics released by the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. In the predominantly white, upper middle class Battery Park, meanwhile, the rate was 85.9 years — over four years above the city’s average.

Over the past decade, life expectancy has risen citywide, and disparities across race have narrowed — but between 2004 and 2013, the gap in life expectancy between very high and low poverty areas widened, suggesting persisting, if not increasing, inequality across income levels.

-Janaki Chadha and Ruth Ford, January 2017

2018

While Subways Get the Spotlight, Bus Riders’ Frustration Grows as Numbers Dwindle

Within recent years, a lot of attention has been paid to fixing subway issues. The MTA announced it’s NYC Subway Action Plan in 2017 and has constantly released information on delays. Another recent report from Stringer’s office shows how even minor delays of just a few minutes can cost New Yorkers over 100 million in a year.

-Angely Mercado, March 2018

But there isn’t an action plan for the bus system or as much information about the number of delays or what they cost commuters. When Mayor de Blasio or Governor Cuomo need to stage a transit-related photo op, they tend to descend the steps to a subway station and maybe step on to a train for a stop or two. They do not stake out a bus stop or crowd onto a packed bus.

2019

See Which NYC Schools Eat Lunch Before 10 a.m.

While Ridgewood residents rushed by Grover Cleveland High School on their way to work Thursday morning, several of the students inside were already counting down the minutes until lunch.

-David Brand, June 2019

Cleveland, a 1,700-student school located in Ridgewood, begins serving the mid-day meal at 9:05 a.m., according to school lunch data in the Office of Food and Nutrition Services’ searchable database. It’s one of at least 100 schools that begin “lunch” before 10 a.m., when many adults are just punching their timecards or scanning their morning emails.

“I heard about that. That’s kind of crazy,” said Brandon, a Cleveland sophomore, as he walked the last four blocks to school a little after 8:30 a.m. Brandon has the opposite problem, he says. His lunch period doesn’t start until 1:38 p.m. “I don’t eat,” he says. “There’s not even a point. I can just go home and eat.”

2020

Decades of Shrinking Hospital Capacity ‘Spelled Disaster’ for New York’s COVID Response

Adi Talwar

The Pediatric Emergency Room entrance at Montefiore Medical Center’s Moses Campus on Bainbridge Avenue In the Bronx in October. (Adi Talwar)More than 40 hospitals in the state have shuttered since 2000, including more than a dozen in the city, accounting for what advocates say was the loss of nearly 21,000 hospital beds statewide during that time. Today, New York’s hospital network has about 53,000 beds.

-Jeanmarie Evelly, April 2020

…

What’s more, experts say, is that the decades of shrinking hospital capacity has made it harder for New York to respond to the current crisis. As of Tuesday, more than 29,000 coronavirus patients were hospitalized in the city, according to Health Department data.

“We would not be in dire straits, calling and having navy ships come into the city,” if many of those now-shuttered facilities had been kept afloat, says Anthony Feliciano, director of the Commission on the Public’s Health System. “I do think we would have had enough beds, at least, to be more prepared.”

2021

Confusion Persists Around State’s Vaccine Plans for Incarcerated New Yorkers

The governor’s initial draft vaccination plan, released in October, included people in congregate settings in its second phase for vaccines, but doesn’t specifically refer to people in jails and prisons. Advocates have been pushing for the state to ensure early vaccine access for people behind bars, citing the high-risk posed by correctional facilities, where spaces are often shared and social distancing difficult. The state’s prison system has seen 27 incarcerated individuals die from COVID-19 between the start of the pandemic and Jan. 5, data shows.

-Nicole Javorsky, January 2021