‘While New York City is experiencing a severe shortage of affordable housing and increase in homelessness both before and amidst the pandemic, landlords are holding thousands of affordable units off the market.’

Sadef Ali Kully

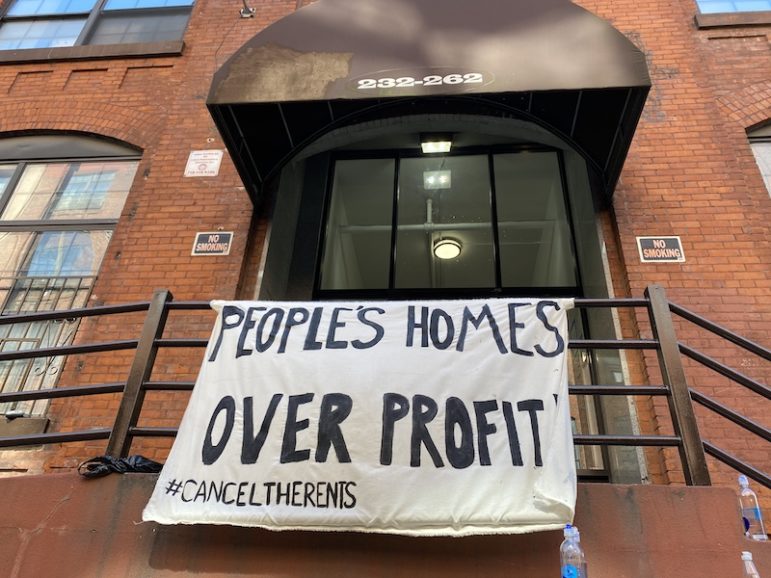

A sign protesting rent collections in Brooklyn during the height of the Coronavirus epidemic.In 2019, Ms. Rosa sat in her apartment where she’s lived for 40 years, worrying about the strange noises she was hearing at night and hoping no one was planning to break in. She had just commuted from the hotel where she was sleeping after illegal construction in her bathroom forced her out of her apartment temporarily. Over 80 years old, she just wanted to be home. Ms. Rosa lives at 149 Irving Ave., owned by Ink Property Group, in Bushwick. One half of the six-unit rent stabilized building has been vacant over two years (one family who had been evicted currently lives in a shelter while their apartment remains empty). The empty apartment next to Ms. Rosa looked almost post-apocalyptic after a leak ran for weeks. When city inspectors finally did gain access to the vacant unit, they wouldn’t enter for fear of their own safety: the black mold coated the walls like paint. Ms. Rosa worried about her health and the health of her neighbors.

While New York City is experiencing a severe shortage of affordable housing and increase in homelessness both before and amidst the pandemic, landlords are holding thousands of affordable units off the market. Many apartments have been warehoused for so long that they have deteriorated to the danger of adjacent neighbors. Tenants are surrounded by apartments left to rot, filled with debris, mold and pests. This is the paradox of warehoused apartments in a city of 92,000 homeless people.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

The consequences are dire. The pandemic has amplified the homelessness crisis already in progress. Some tenants are being driven out of their homes as overcrowded rooms and shelters lend themselves to spreading COVID-19. Those experiencing homelessness are dying at a 61 percent higher rate than the general population while the city is simultaneously experiencing one of the biggest vacancy rates in years. This is unconscionable. We can no longer afford to allow housing to sit unused while COVID-19 threatens our city and state.

Meanwhile, some landlords have intentionally created mostly-empty buildings, leaving remaining tenants surrounded by warehoused units. In one 15-building portfolio in the Lower East Side, over half of the 281 apartments have been sitting vacant for more than four years. Not coincidentally, many of those apartments are rent-regulated. Some were gutted as the new owner planned to convert them into market-rate, luxury, 5 and 6 floor walk-ups. Others remain habitable but empty. In north Brooklyn, a few rent-regulated tenants survive in their otherwise vacant rent-stabilized building.

But why are landlords choosing to leave so many apartments vacant? Doesn’t this go against all sense of good business? After NY State’s Housing and Tenant Protection Act of 2019, landlords found new ways to deregulate apartments and raise rents. If two vacant apartments are combined—commonly now called “Frankensteined”—landlords are able to raise the base rent to whatever they like, essentially deregulating the units. Some hope that remaining tenants in near-empty buildings would clear out, so multiple apartments could be combined or to fully demolish and renovate the building into new, unregulated units. Data pulled from the Department of Buildings shows that 341 applications to combine two apartments were approved since January 1, 2019, meaning that almost 700 rent stabilized units were permanently lost due to this practice. Other landlords are simply waiting for the tenant-friendly legislative body in Albany to shift. According to a Real Deal article published in September, many landlords “don’t blame Covid as much as they do the new law’s limits on how much landlords can be reimbursed for renovations. Some landlords also say they are reluctant to fill vacant apartments because they think state legislators might change the law in their favor.”

As the COVID-19 crisis drags on with no end in sight, more and more units are being vacated. A Crain’s article this month reports that vacancies in Manhattan reached a record high, with close to 16,000 available to rent.

There are tangible solutions. The End Warehousing Coalition, which came together to address this crisis, is inspired by cities around the world responding to the problem of warehoused units. Barcelona is forcing landlords to rent out empty apartments within thirty days or face the possibility of having the dwellings seized by the city. Los Angeles is exploring a tax on vacant apartments, which would push landlords to rent rather than sit on their housing stock. More and more creative solutions are emerging worldwide to ensure housing for all during a pandemic. New York should be a leader in this movement.

Our coalition is working with the New York City Council and the New York State government to advance legislation which would create a registry of vacant units, mandate inspections of those units, and fine landlords who are holding affordable apartments empty. Money generated from those fines could feed into a voucher program to fund housing for the homeless. Another proposed policy would automatically reduce residential rents to the federally-determined fair market rates and require landlords to accept housing vouchers from low-income and homeless applicants.

We need an affordable solution for New Yorkers. Our tax money should not support warehousing any affordable units, especially in private buildings that receive government subsidies. New York City and state can and must develop immediate policy solutions to this crisis.

The authors are members of the End Warehousing Coalition, which is made up of several organizations including St Nicks Alliance, Los Sures, the Cooper Square Committee, Tenants Taking Control, United Neighbors Organization, Los Sures LUCHA!, Communities Resist, Housing Conservation Coordinators, Stellar Tenants for Affordable Housing, and Citizen Action NY.

29 thoughts on “Opinion: NY Must Act to Stop ‘Warehousing’ of Vacant Affordable Apartments”

‘…Our coalition is working with the New York City Council and the New York State government to advance legislation which would create a registry of vacant units, mandate inspections of those units, and fine landlords who are holding affordable apartments empty…’

All of doubtful constitutionality.

This is pure tenant propaganda. There are an enormous amount of apts vacant at the moment that are not rent regulated that are trying to be rented. And again you want to punish landlords for that too. Tax vacant apts? There has been no assistance for rent apt buildings during Covid. A time when there has been a mass exodus from nyc and a large % of tenants unable or unwilling to pay their rent. Yes, there is a homeless problem in NY, but why are you forcing private individuals to foot the bill to house them particularly those that do not get any government tax credits. There is so much talk about making housing available to low income people, yet you’ve done nothing to insure that those that are deserving get them. There is no registry, no oversight and no qualifications for getting and keeping a rent regulated apt. You can be a millionaire with multiple other homes, but as long as you live in your apt as your primary residence you can get and keep your regulated apt forever and then pass it on once you’re gone. So really who is warehousing apts, the landlords or the rich tenants that will never give up their deal of the century!? For some real unbiased information look to the citizens budget commission.

Elizabeth,

You know that’s is a bunch of hot air. Landlord’s in the city are not renting to low income people at all. You look and look and it’s very difficult to find available units.

Well excuse me to say Elizabeth but you must clearly not live in NYC to know the living situation here or just a silly little rich chick with out a care in the world but her own ego or maybe your a landlord we would never know, but the reality is that this is a big problem before the pandemic that everyone who lives in NYC should be taking action by all nyc citizens and honestly I don’t know what the HELL us the people are waiting for i guess till the entire nyc population gets to be homeless or something but these NYC landlords are taking advantage of everyone they are raising high unexplainable rents that actually makes no sense that even in nyc most worsted neighborhoods have these$ 2,000 / month rent , the apartments are not luxury apts ALL NYC APTS ARE VERYYYYYYY……….. OLD THEY ARE FALLING APART THEY ARE INFESTED WITH PEST THE WALLS ARE ALL MOLDY THE PIPES and drainage systems are ALL OLD ,RUSTY, INFECTED WITH BACTERIA( like lead)BECAUSE OF INPROPER FILTRATION and guess what nyc landlords are cheap they don’t like to pay for the proper service in fixing their rental building they prefer to cover all the walls up with plaster, paper, and paint and just disguise them into looking like beautiful apartments when the truth is they are rotting inside with mold , which is a serious risk to all our health especially during covid19 i bet many patients who had covid19 had some kind of mold related issue and probably had no idea they had mold in their walls i bet if we conduct an inspection in all the patients who got infected with covid19 all their walls or somewhere in the apartments or building most have had mold we should put that to a test and i bet the only ones we could blame are THE POTENTIAL LANDLORDS but back to business LANDLORDS ARE SIMPLY CHARGING TOOOOO…. MUCH for these apartments that are not worth the price they are renting them for, THIS AFFORDABLE HOUSING LOTTERY IS ALL BALOGNE this word AFFORDABLE is just a disguise for the rich to be able to live in our low poverty communities paying AFFORDABLE rent for them selves this is where the word AFFORDABLE plays the role. I been applying for affordable housing lotteries in nyc for 10 yrs I have 2 children and because of this ridiculous rent rise and these ridiculous amounts of incomes this system is asking for you to make is impossible, you will just work to pay rent and nothing else you won’t even be able to afford groceries for a family of 4 with these prices and it needs to change this is 2020 we are still with this stone age methods what worked 10 yrs ago is not going to work now we need new strategies and i can’t WAIT TILL THESE EXTREME MEASURES START TAKING ACTIONS.

Rochelle – you obvious do not know what it is like to run a building especially pre war buildings that were forced against the constitutional rights of Americans to provide the subsidy known as rent stabilized and rent control apartments whereby not receiving the just compensation from the government for that taking. Now history lesson aside, here is the microeconmic reality of your false accusations and unsupported rhetoric – particularly this statement “nyc landlords are cheap they don’t like to pay for the proper service in fixing their rental building they prefer to cover all the walls up with plaster, paper, and paint and just disguise them into looking like beautiful apartments when the truth is they are rotting inside with mold” if you are not an environmental engineer and have not tested the surfaces, don’t exaggerate and say without investigating that walls have rotting mold. Also exaggerating that NYC landlords are cheap is not true for all. There are many small property owners who can not afford the requirements because rents are forced to be too while maintaining inflated NYC Property taxes and insurance and utilities and while trying to provide a living wage to workers as well as employee insurance and payroll taxes. This is in addition to tenants who willfully damage apartments and cause expenses to also increase. You are taking a look at your own unfortunate situation and because you can’t catch the lucky break you think you deserve by having a government hand out, you automatically project and blame your anger on others. Why don’t you look at the people who have multiple homes who were lucky enough to get their hands on a rent regulated apartment and holding onto it to give to their family member and not letting people like you get a chance to move into them?

Until you walk a mile in someone’s shoes, then don’t assume you know what it’s like so keep your false narrative to yourself and go focus on your own life and get yourself into a better situation so you won’t continue spreading incorrect statements.

Dude, NYC is a terrible place.

Rents here are a scam… and for what? I don’t understand it. You get here and get trapped by the rich. The poor become zombies.

If you make less than 75,000 a year: your life here probably sucks.

I don’t understand how this apartment is at $2,000 for 300 sqft- when it’s worth $500. That is a bigger issue that needs to be tackled. The macroeconomics of living a good life in NYC has dumbfounded me.

Wow. That’s just pure hatred!

Elizabeth is 100% correct. Nothing she has stated is false. Why don’t you address her legitimate points?!

Democrats don’t care whether something is constitutional or not

Yes I agree with what you are doing for low income people. My daughter is seeking an apartment for her and my granddaughter in a good neighborhood with parks and a lot of places were we know that have affordable apartments are just telling her No we don’t have.

This is real, homelessness. Its going to get worst. Because rent continues to go up. and race plays a part also when people go find apartment. Also single homeless adults and persons with a disabilty continue to make up most of the homelessness. What needs to be done. stop saying the affordable apartments because there not for people who make under 30 thousand. There for people making over 50 thousand and up.

Great article.

I hope your coalition will also consider the Georgist solution of taxing land and not buildings. This will encourage building more buildings, while discouraging warehousing and speculating on land values. It’s been tried for over 100 years in cities all over the world. Our organization, Common Ground USA has 100s of studies showing it works.

Let me know if you are interested.

Scott Baker

Former president of Common Ground-NYC, member of Common Ground-USA

http://commongroundnyc.org/

Scott, this ‘LVT’ sounds like a scam to me. How would LVT help reduce property taxes on 1 & 2 family homes?

Thérés a a lot more thane 92000 homeless in NY. Thérés probably about 150000 currently homeless & about 100,000 more at risk of being homeless- im a retired Social Worker who Dealt with homelessness in 3 différent states including NY. This has been a constant problem in NY for décades. To bad they cant get it wright.

My bldg in 10025 has 47 empties. Out of 120 units. How is that healthy for nyc?

We’d love to be in touch and learn more about your building. feel free to email me at egoldin@stnicksalliance.org.

Democrats don’t care whether something is constitutional or not

they have 47 empties and lemme guess are still unwilling to lower rents- right? because omg last year we had them at x3 or x4 the price.

Well, the truth is- nyc is a shitty place and rich landlords don’t understand this. Guidable first-timers accept these rents who think they are getting a deal, but in reality- these rents should be like $500

” Another proposed policy would automatically reduce residential rents to the federally-determined fair market rates ”

Reduce? Most warehoused apartments are well BELOW the federally determined fair market rates. Apartments that rented for $400, $700, etc. that would be rented in heartbeat if the landlords could just get the “federally determined fair market rate”. NYC Rent Guidelines board estimates that unit maintenance costs almost $1100 a month. Why should landlords be forced to rent apartments for less than it costs to maintain them???

Exactly

Well that’s logic right? But if logical statements counter the idea of “giving something to people for free” then they will just refuse to accept that. Agreed that NY RGB is not taking into account the true costs in operating a building.

NYC, must get millonaires out of rent control apartments and get low income people in there that really need the apartment. As peoples income increase they can stay in the apartment to a point but landlord should be able to raise their rent to correpond eith new income. Why should landlords lose money ti supply housing? Do other businesses have to lose money so people can pay for there services?

I am perpetually thought about this, appreciate it for putting up.

Hey very cool web site!! Man .. Excellent ..

Amazing .. I’ll bookmark your website and take the feeds additionally?

I am happy to search out a lot of helpful information here

within the put up, we want work out more

techniques in this regard, thank you for sharing.

. . . . .

This is completely justifiable as the state dictates how much an owner can charge yet the costs continue to rise.

As a landlord with rent-stabilized apartments I am leaving all my vacant apartments empty. I would love to rent them if the state let me earn a reasonable rate but am no way interested in essentially giving away my property rights under the socialist rent-regulation scheme here in NYC/S.

Until the courts rule the NYS appropriation of property rights unconstitutional, I will simply use my vacant apartments for storage or let friends and family use them. The state will not force me to provide a service against my will at a price they dictate.

One last thought: If rent regulations did not exist, and all [private] units were market rate, you would never see cases like that of Ms. Rosa; property owners would do everything they could to make their properties as attractive as possible and retain good tenants. Harassment cases would evaporate overnight as there would be zero motivation for landlords to harass a tenant in as much as if the owner wanted to recover the unit, they would simply wait until the lease expires. AND we could eliminate a large body of costly and useless bureaucracy (e.g. HPD, RGB) as well as increase tax revenue.

The

I moved to New York about 2 years ago and don’t know much about rent stabilization.. but it seems to me that it had existed for many many decades. If it was unconstitutional, I am sure landlords would’ve taken the city to the supreme court and easily won.

In fact, I think (not sure though) that when the land was initially purchased from the city or possibly when the license to build was first obtained, the developer got a break in price or was allowed a higher building, in return for assigning a certain percentage of units to affordable housing.

Thus, if the initial purchase agreement stipulated a some rent restrictions, then that’s what it is.. you cannot ask for that stipulation to be removed, even a 100 years later. It is already factored into the price of the building you bought.

So stop calling it unconstitutional.. that’s misleading

I want to relocate there long-term or permanently Just a bit confused as to why this is happening? What benefit is there keeping properties vacant? If landlords are collecting government subsidies by not renting is unethical.

My experience:

To visit NYC (4 times now) seems cool with the locals but try to move in prior to living there already, forget it! Crazy questions, scammers, fake ads, change rent price, pay upfront, show up no room, hurry up, wait, next week, on and on.

Crazy…..

The landlords with rent-stabilized apartments DO NOT collect subsidies – that is the whole point, as private individuals they are directly subsidizing the tenants with the artificially deflated rents.

What is the benefit of keeping them vacant? Numerous possible reasons:

1. The cost to maintain the apartment is more than the “legal” rent an owner can charge.

2. The owner wants to live in their own building so is waiting for tenants to vacate.

3. The owners are not willing to submit to the draconian regulations.

And again, all of this intrusion on private contracts and agreements is justified by a 50+ year “housing emergency” that the city declares blindly every three years.

If there were no price caps and coerced lease renewals, 47% of the units would be back in the market and prices would drop for everyone on average. Builders would also be motivated to provide more housing.

It’s simple economics and logic, but the Democrats in this state are just craven opportunists given there are more renters in NYC than owners.