‘Research has found that as many as 50 percent of formerly incarcerated New Yorkers who are re-enfranchised mistakenly think that they remain ineligible to vote.’

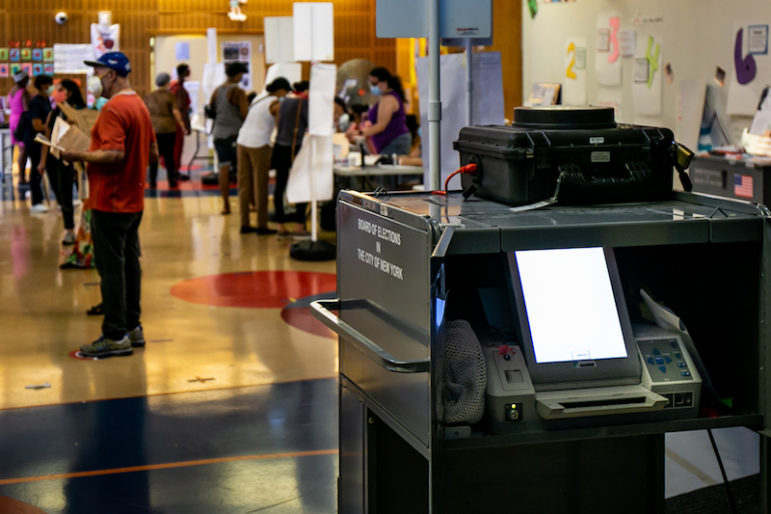

Adi Talwar

A ballot-marking device at P.S. 94 in the Bronx on Primary Day.Voter suppression in New York is alive and well, though its forms here have kept a lower profile than in other states. This lack of visibility does nothing to mitigate the deleterious effects it has wrought for communities of color and people with criminal justice involvement, and has only fed the disillusionment that many of those impacted feel with the political process.

As the 2020 Presidential election rapidly approaches, long-standing methods of voter suppression have been brought to the forefront of the national conversation. Active tactics used to deter potential voters, including the recent ruling in Florida that effectively applied a poll tax to a large swath of formerly incarcerated voters, and the closure of polling sites in Black and Brown communities, have drawn wide attention across the country.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

In New York, we generally consider ourselves exempt from the kinds of overtly suppressive policies that exist in states with well-known histories of disenfranchisement. Yet New York must contend with its own insidious system of passive voter suppression, a network of invisible forces—from logistical barriers to the uneven distribution of resources and voter engagement efforts—that combined to give the state the 8th lowest voter turnout in the 2018 election.

Recent studies have shown the suppressive effects of campaign finance strategies in low-income communities, where lower rates of registration and voting history have led many political campaigns to further disengage because they deem the costs of voter mobilization to be too high. Understandably, such calculations of political worth have led those left behind to believe that voting and civic participation are not designed to include them, much less produce tangible differences in their lives.

For the disproportionately Black and Brown New Yorkers with a felony conviction, previous involvement with the criminal justice system only magnifies these hurdles and cements a system of de facto disenfranchisement that lands most heavily on their already largely disadvantaged communities.

Formerly incarcerated New Yorkers face some of the most confusing eligibility rules in the country. While New York law actually restores voting rights to a large proportion of state residents with felony convictions, including everyone who has completed their sentence or is on probation, the guidelines and requirements to register are often prohibitively opaque and misinformation is rampant.

Though people on parole are not generally eligible to vote in New York, a 2018 executive order from Gov. Andrew Cuomo has restored voting rights to almost 50,000 New Yorkers currently on parole, and pardons are granted on a continuing basis. It is parole officers who are charged with letting individuals know they have received these rights. The irony being that New York is the state with the second highest number of people sent back to prison based on parole violations, so the choice to use these individuals as a messenger makes little to no sense.

Research has found that as many as 50 percent of formerly incarcerated New Yorkers who are re-enfranchised mistakenly think that they remain ineligible to vote as a result of these miscommunications. And many who receive misinformation about their voting eligibility a first time are unlikely to follow-up in the future. Ultimately, voting rates among formerly incarcerated, eligible New Yorkers are estimated to be in the single digits, highlighting the profound effects of these alternate forms of voter suppression on this community. It is imperative that we work to remedy and disrupt these cycles through legislative education and voter mobilization campaigns that center the experiences and needs of these marginalized populations and employ peer messengers. Reversing the effects of de facto disenfranchisement and re-empowering these New Yorkers to make their voices heard at the ballot box will allow us to elect a new generation of lawmakers who can finally be held accountable to the demands of the full body of people they represent.

Ivelisse Gilestra is a formerly incarcerated advocate and the community organizer for College & Community Fellowship. She is the lead on Justice Votes NY, a campaign to educate New Yorkers with criminal justice-involvement about their right to vote.